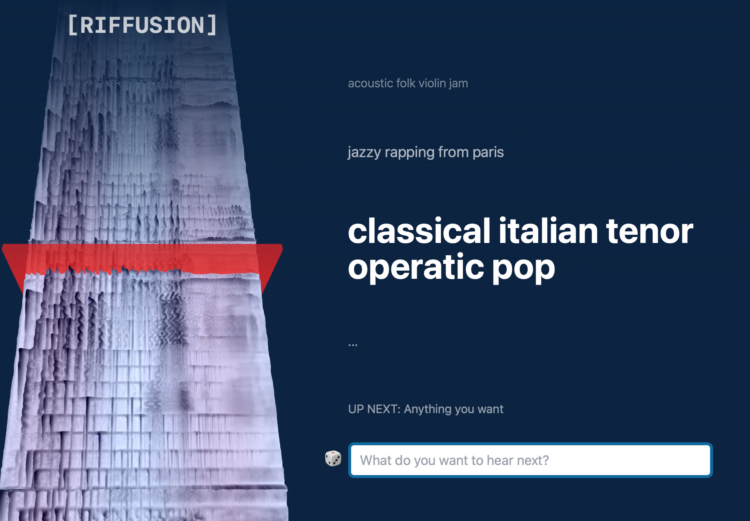

Lensa is an app that lets you retouch photos, and it recently added a feature that uses Stable Diffusion to generate AI-assisted portraits. While fun for some, the feature reveals biases in the underlying dataset. Melissa Heikkilä, for MIT Technology Review, describes problematic biases towards sexualized images for some groups:

Lensa generates its avatars using Stable Diffusion, an open-source AI model that generates images based on text prompts. Stable Diffusion is built using LAION-5B, a massive open-source data set that has been compiled by scraping images off the internet.

And because the internet is overflowing with images of naked or barely dressed women, and pictures reflecting sexist, racist stereotypes, the data set is also skewed toward these kinds of images.

This leads to AI models that sexualize women regardless of whether they want to be depicted that way, Caliskan says—especially women with identities that have been historically disadvantaged.

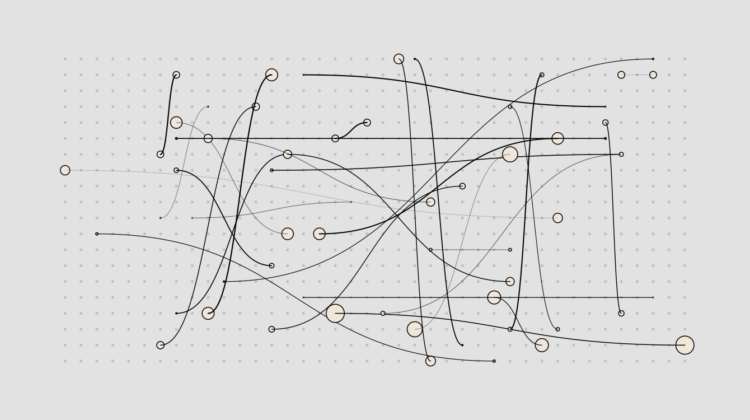

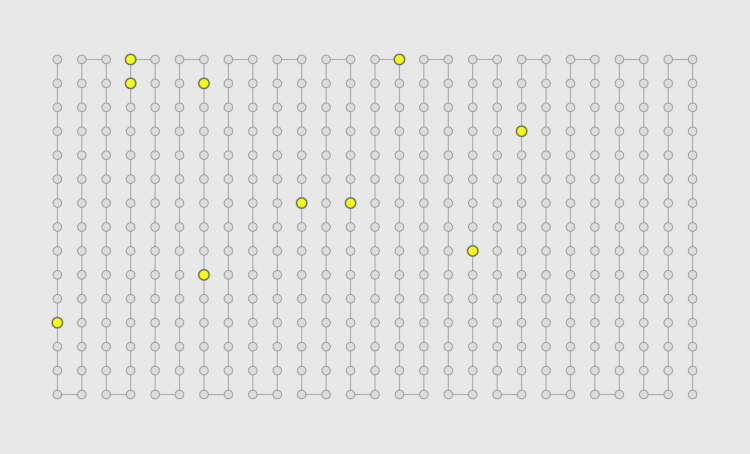

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)