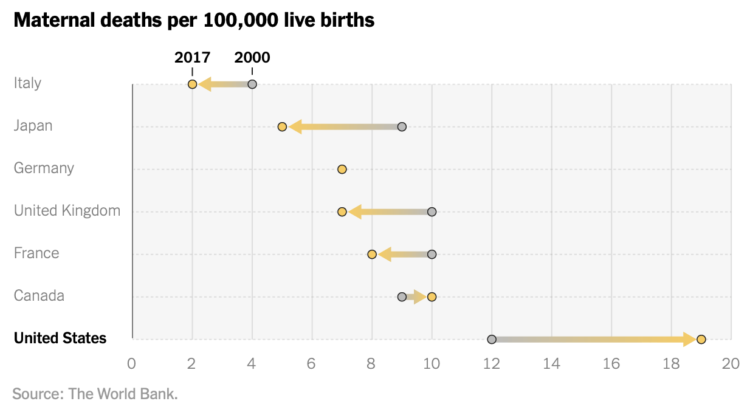

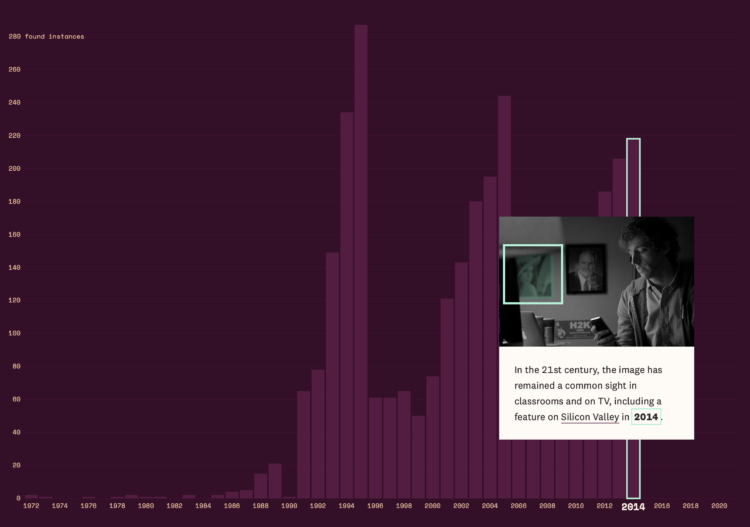

While still relatively rare, maternal mortality in the United States increased over the years. In most other developed countries, rates decreased over the same time period. From NYT Opinion:

Over the past two decades, maternal mortality has increased almost 60 percent. The United States is the only other Group of 7 country besides Canada to experience such a drastic decline in maternal health. (Canada saw a minor increase in pregnancy-related deaths.)

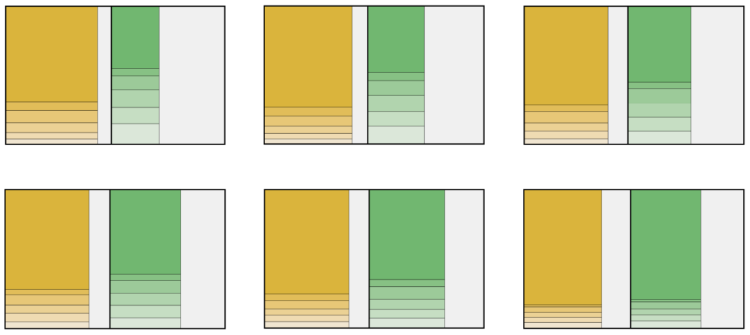

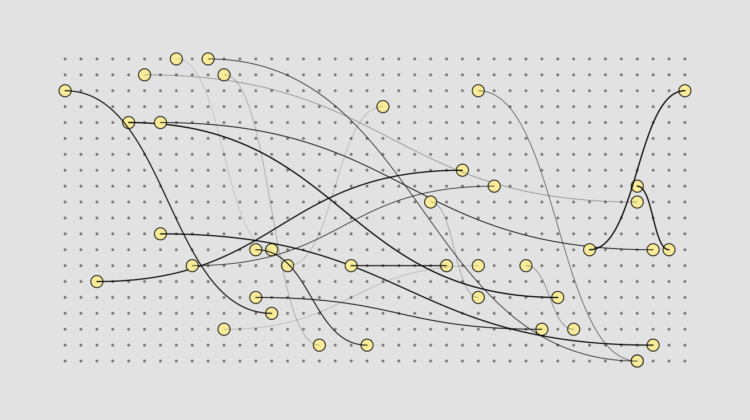

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)