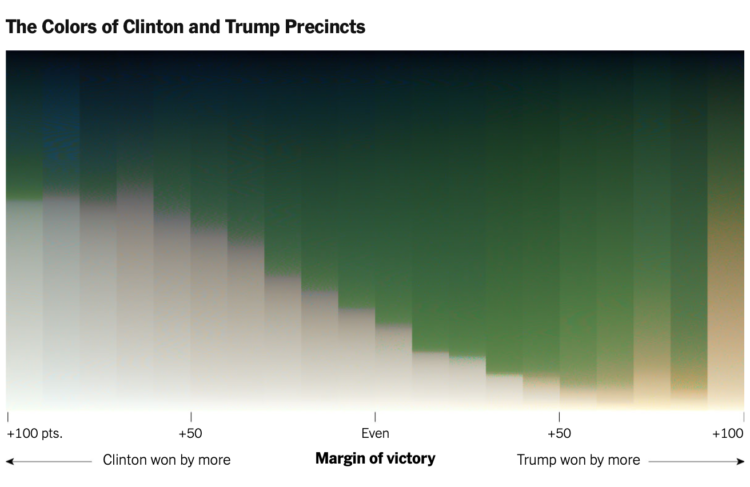

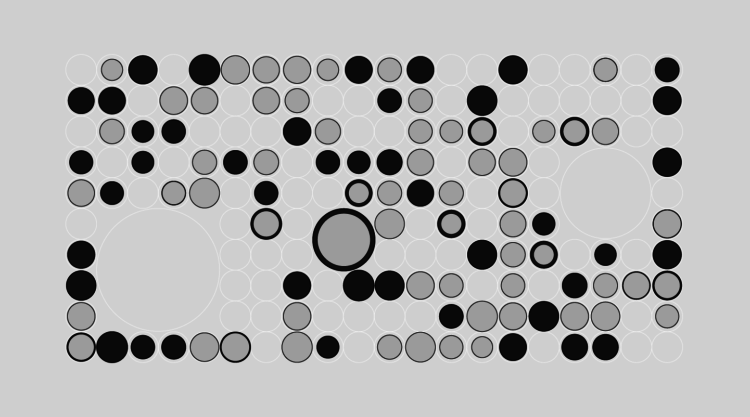

For NYT’s The Upshot, Tim Wallace and Krishna Karra looked at how the red-blue electoral map relates to the green and gray color spectrum in satellite imagery:

The pattern we observe here is consistent with the urban-rural divide we’re accustomed to seeing on traditional maps of election results. What spans the divide — the suburbs represented by transition colors — can be crucial to winning elections. It’s part of why President Trump, seeking to appeal to swing voters, has portrayed the suburbs as under siege and menaced by crime. But the suburbs are neither politically nor geographically monolithic. They are where Democratic and Republican voters meet and overlap, in a variety of ways.

The breakdown and process are impressive. Be sure to check out the full rundown. Wallace also provides more details about how this came together on the Twitter.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)