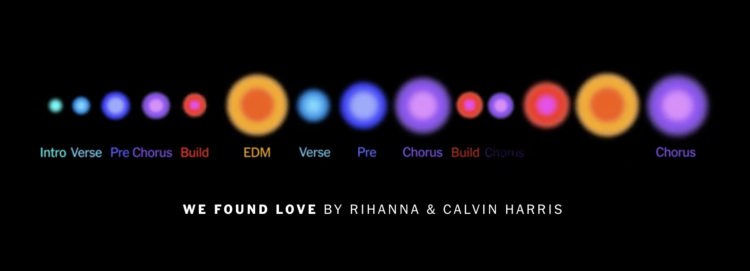

Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding, for NYT Opinion, look at how the structure of songs have changed to fit with the current methods that people consume media:

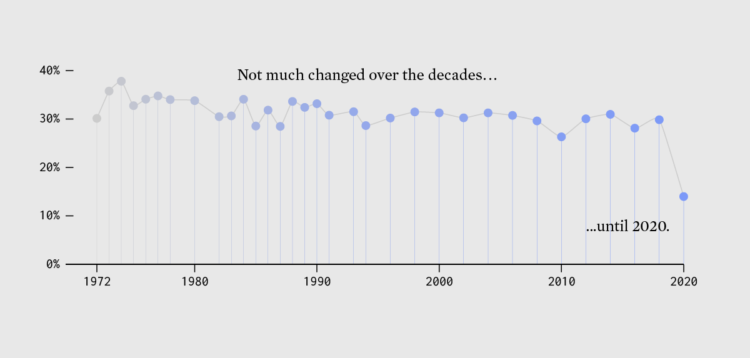

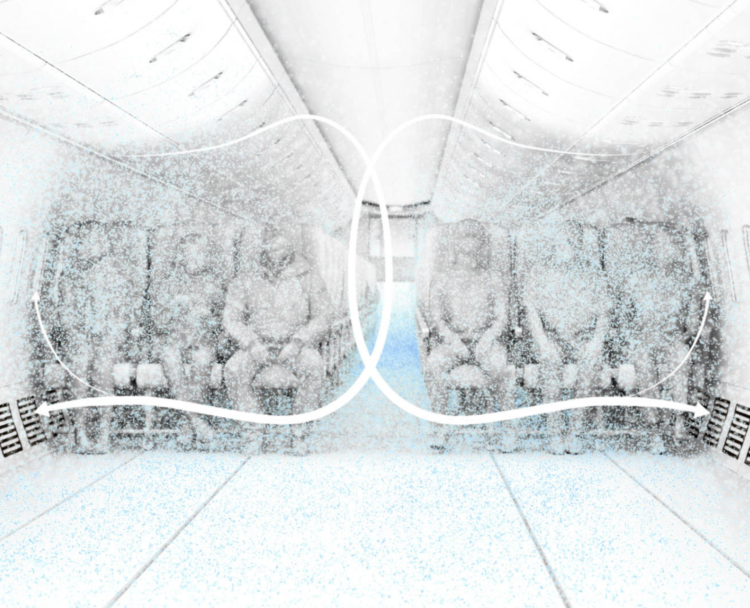

It’s inescapable that today’s aspiring artists and songwriters must operate, for survival, in a landscape of streaming services and social media. From Spotify to TikTok, the goal is to create music that will grab a listener’s attention from beginning to end. You’re not just competing against other creators. You’re also competing against everything else that takes up our time: podcasts, TV, apps and more. So to keep streaming consumers engaged, it is increasingly common for songs to begin in medias res — with a hook, followed by a hook and ending with another hook.

Put your headphones on and turn the volume up for maximum effect. The combination of the songs, visual breakdown, and words work well together to help you understand song structure.

Now I know why my brain is often confused when I hear a full song, instead of a looping chorus on TikTok.

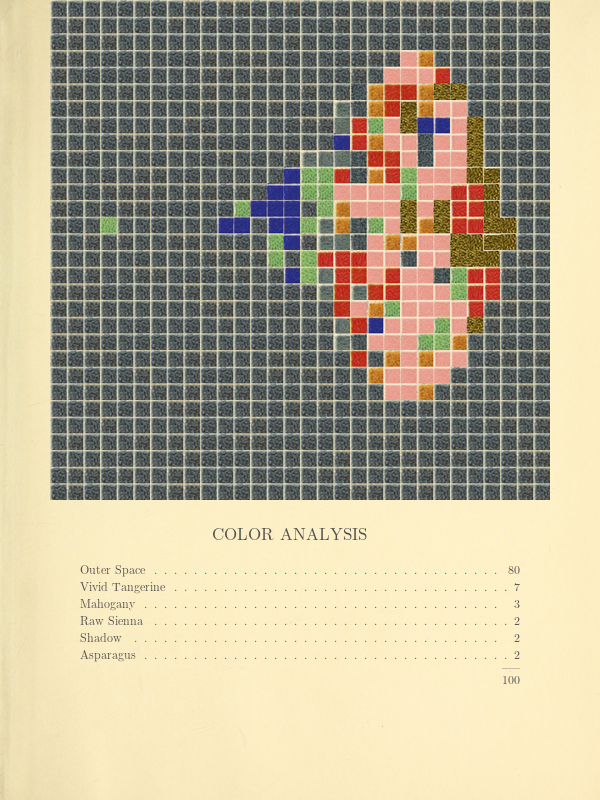

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)