-

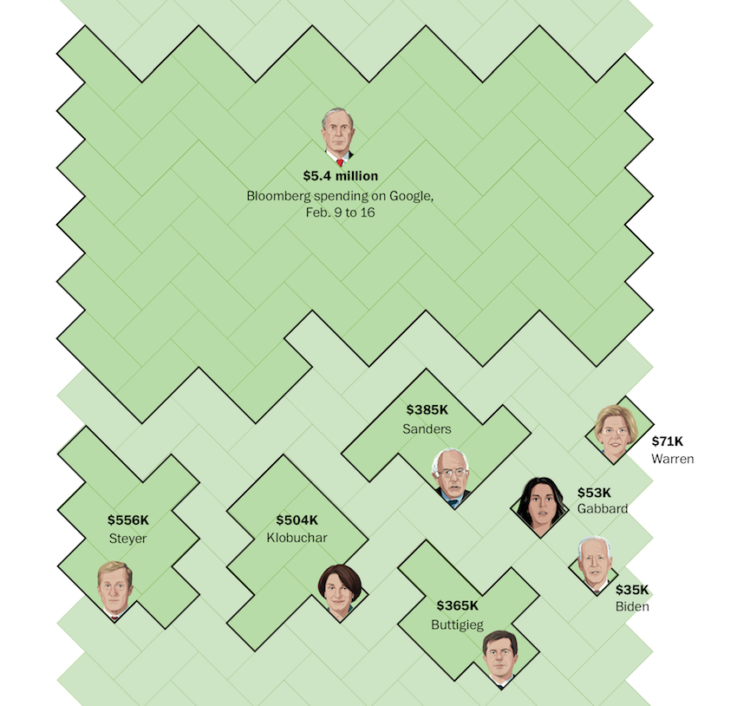

Mike Bloomberg’s ad spending might not be that much relative to his own net worth, but compared to other candidates’ spending, it’s a whole lot of money. The Washington Post puts the spending into perspective with a long scroller. Each rectangle represents $100k, and there are “mile markers” along the way to keep you anchored on the scale.

-

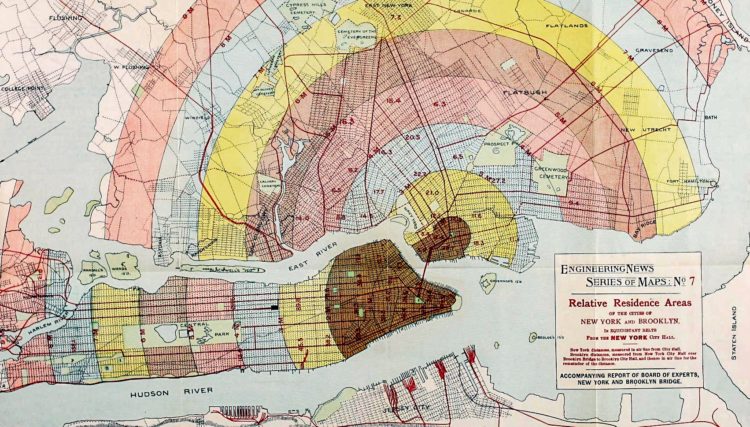

Geographer Tim Wallace likes to look at old maps, and is particularly fond of the weird and forgotten types:

So, I slowly amassed a more complete list. And here it is. Most of these map types are silly or unusual, not forgotten. Many of them are even deliberately taken out of context to highlight their wackiness and how easily maps can be misread (I sure misread them all the time!).

It’s fun poking around the Internet Archive and HathiTrust, blowing the digital dust off of a volume with 0 views and having a look. You never know what you’ll find. Maybe a forgotten map type?

The above is the long forgotten but everlasting Gobstopper zone map.

-

Adobe Illustrator has charting functions that can be useful if you’re on a deadline. Make a quick chart, design, and publish. However, if you want to reuse the chart with new data or need to use a more complex chart type, it’s usually been better to use different software and then come back to Illustrator to adjust.

Datylon Graph is an extension that aims to make it easier to stay in Illustrator for your full workflow. It promises reusable charts, collaborative tools, and a growing visualization library.

It currently starts at €7.50 per month with a 14-day free trial. I’m skeptical about working completely in Illustrator, but I’ll have to kick the tires on this soon.

-

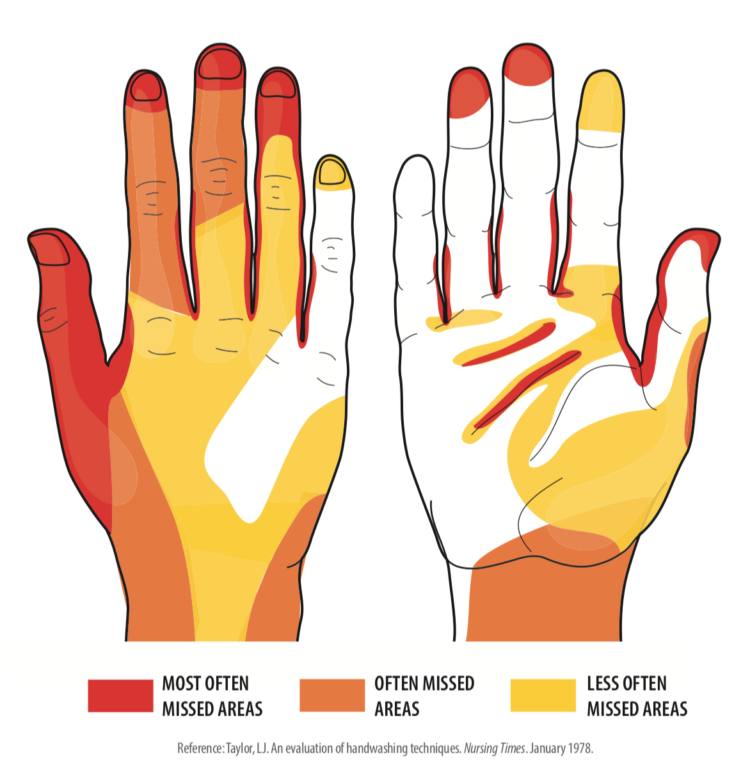

This graphic from WakeMed shows the areas most often missed while washing hands. It’s based on an old-ish study from 1978 by Taylor LJ that evaluated handwashing techniques by health professionals. I’m guessing (hoping) that technique has improved since then.

Also, if there were a diagram based on data collected from the men’s room, the hands would just be completely colored red. Wash your hands, please. It’s kind of important right now.

-

Botnet is a social media app where you’re the only human among a million bots trained on social media activity. Post pictures, status updates, or whatever else you want. Then let the likes and weird comments roll in.

You can even purchase troll bots, bots that tell dad jokes, and more bots.

Social media is on its way to mostly being bots anyways. Might as well jumpstart the future. Artificial intelligence for the win.

-

Members Only

-

Neal Agarwal used a money printing metaphor to depict differences in various wages. The higher the wage, the faster the money prints. Keep scrolling and you also see big company revenues, finished with a frantic U.S. deficit increase.

So good. [Thanks, Neal]

-

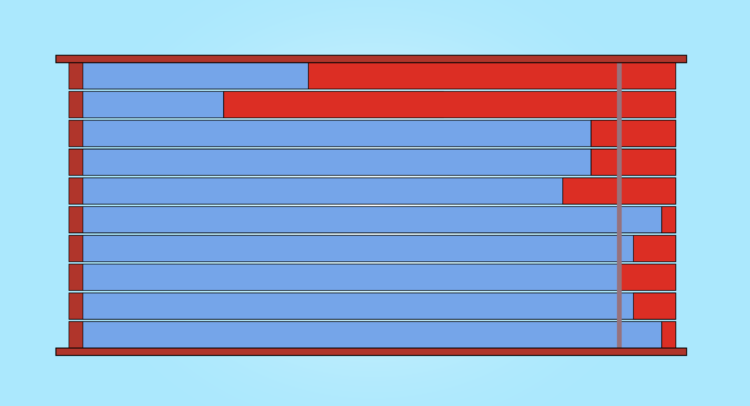

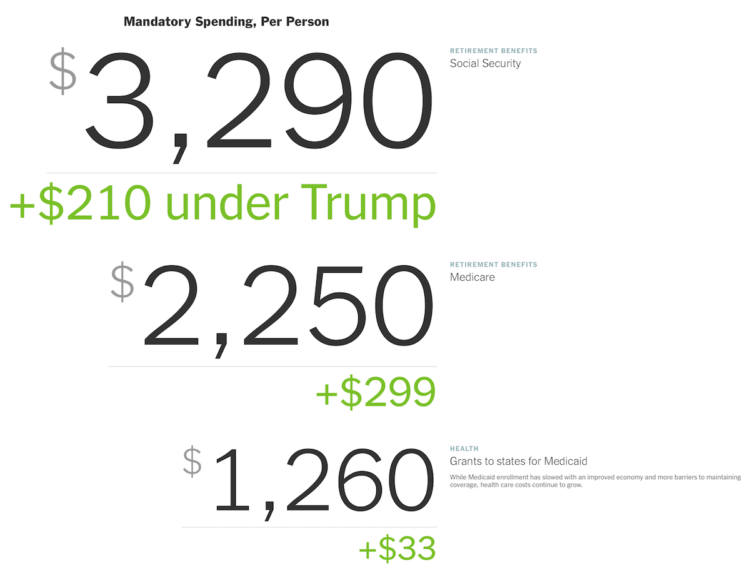

For The Upshot, Alicia Parlapiano and Quoctrung Bui scaled down the federal budget to something more relatable:

To better understand how federal spending has changed since Mr. Trump has taken office, we looked at the actual budget amounts for the 2020 fiscal year. We divided them by the U.S. population and sized the numbers proportionally to make their scale easier to visualize. Then we compared the numbers to the actual budget for the 2016 fiscal year, adjusting for inflation and population changes.

Federal budget visualizations usually aim to show big dollar values going to many different departments. You look at the breakdowns, and you can’t help but think, “That’s a lot of money.” For most of us, it’s hard to imagine billions of dollars, because the scale is so far beyond our own experiences.

So it’s interesting that this piece goes the other direction and scales everything down to match the values to something more familiar. The font size of each value also scales accordingly, which I think in the end is what you end up focusing on.

-

Reddit user quantum-kate used daily high and low temperatures in Denver in 1992 as the basis of this blanket. I feel like I should learn to

knitcrochet. -

DR used a 3-D model to recreate King Frederick the 9th’s ink:

King Frederick the 9th was famous for his tattoos. But until recently — noone knew much about them. By examining hundreds of old photographs and films we have recreated the Kings’ ink in order to get a sence of who he was — both on the inside and the outside.

The scrolly touring works really well here. I went in knowing nothing about the king and came out more educated on the other side.

-

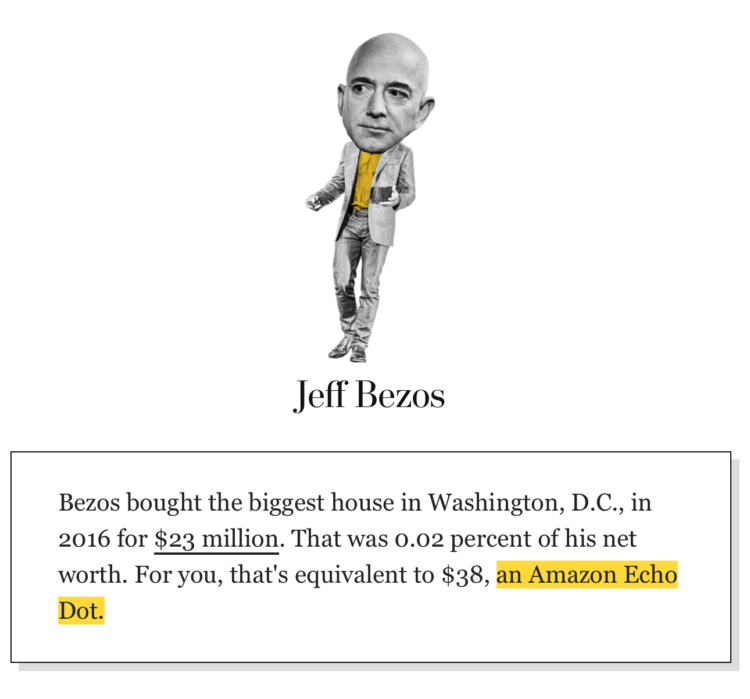

We hear about billionaires spending millions of dollars on ads, acquisitions, etc. It seems like a ridiculous amount of money, but that’s partially because us common folk think of the millions of dollars in the context of our own net worth. When Jeff Bezos spends a few multiples of what we will never make in a lifetime, it seems like a lot.

For The Washington Post, Michelle Ye Hee Lee and Youjin Shin made an interactive that instead looks at the spending as a percentage of net worth. The purchases suddenly seem less crazy (sort of).

It’s simple math but a nice way to make the spending scales more relatable.

-

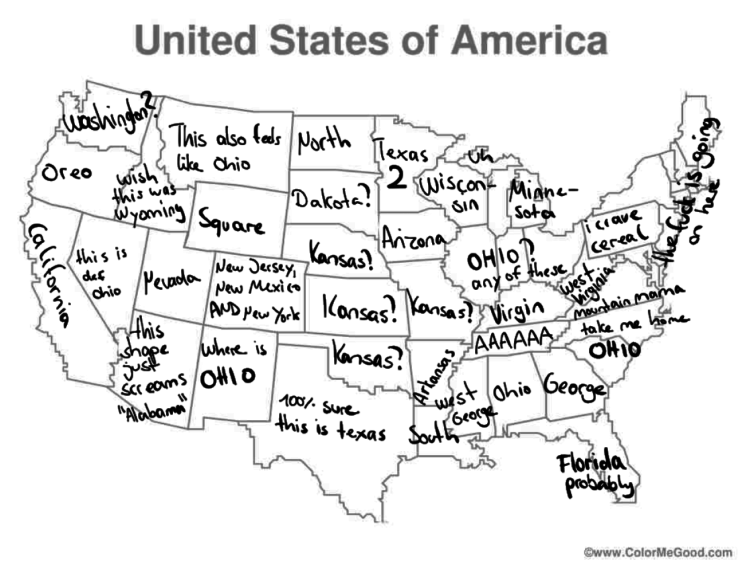

From @haru_cchii on the Twitter:

Local German Gets Bored And Tries To Name All American States

i think i did pretty well

Seems right to me.

-

It wasn’t just issues with an app. There appears to be many more problems with the Iowa caucus results. The Upshot broke it down with a closer look at the data:

Some of these inconsistencies may prove to be innocuous, and they do not indicate an intentional effort to compromise or rig the result. There is no apparent bias in favor of the leaders Pete Buttigieg or Bernie Sanders, meaning the overall effect on the winner’s margin may be small.

But not all of the errors are minor, and they raise questions about whether the public will ever get a completely precise account of the Iowa results. With Mr. Sanders closing to within 0.1 percentage points with 97 percent of 1,765 precincts reporting, the race could easily grow close enough for even the most minor errors to delay a final projection or raise doubts about a declared winner.

When did voting get so complicated?

-

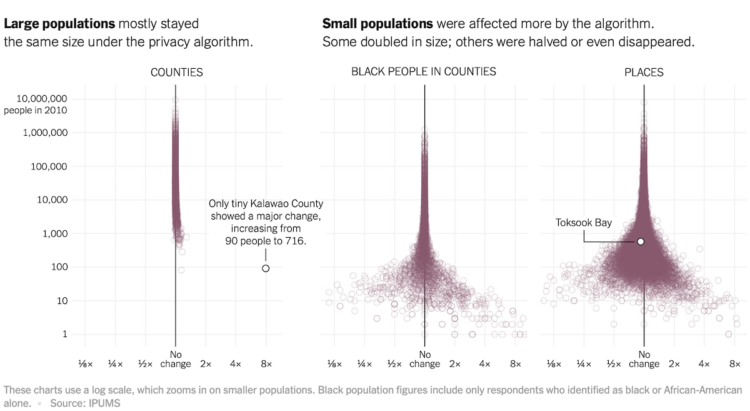

To increase anonymity in the Census records, the bureau is testing an algorithm that removes real people and inserts imaginary people in various locations. As you can imagine, this carries a set of challenges. Gus Wezerek and David Van Riper for New York Times Opinion ask what effects this could have on small towns. [Thanks, Gus]

-

Members Only

-

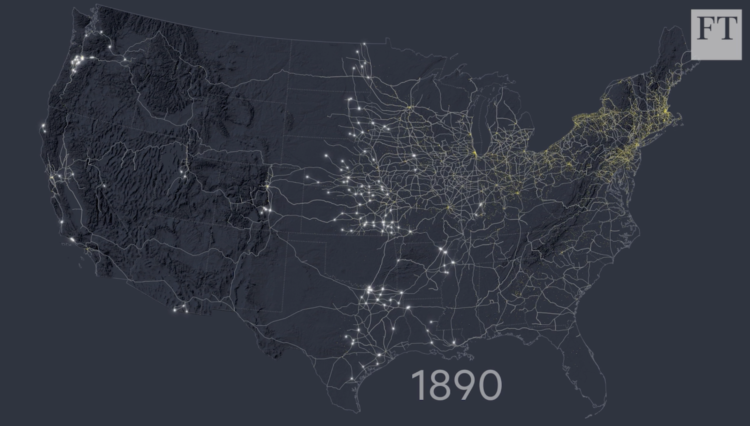

For the Financial Times, Alan Smith and Steven Bernard traced the history of railroad construction in America and mapped it over time. Literally. Bernard used digitized versions of old maps and traced each new segment by hand. Tedious, but the result is impressive.

-

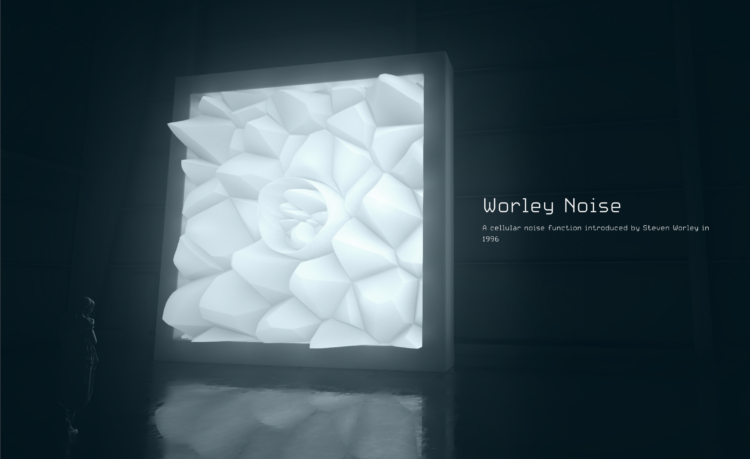

From Lusion, CineShader is a fun editor for those who are familiar with Shadertoy:

CineShader is a real-time 3D shader visualiser. It leverages the Shadertoy.com API to bring thousands of existing shader artworks into a cinematic 3D environment.

The whole project was started as an idea of using a web demo to explain what procedural noise is to our clients at Lusion. After sending out the demo to some of our friends, we were encouraged to add the live editor support and we decided to release it to the public.

-

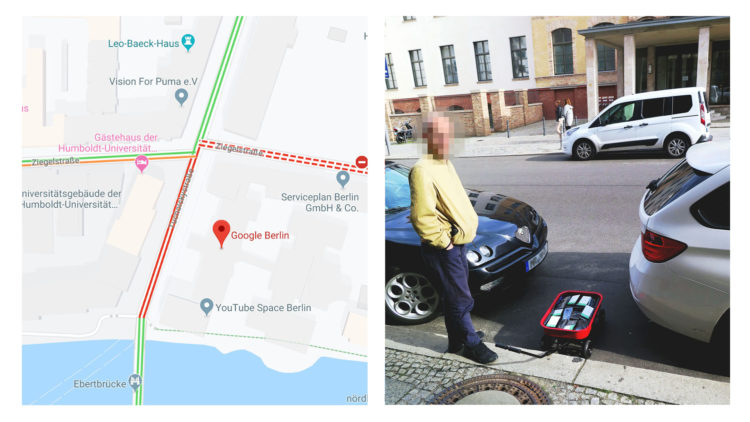

Google Maps incorporates data from smartphones to estimate traffic in any given location. Artist Simon Weckert used this tidbit to throw the statistical models off the scent. With a wagon of 99 smartphones, he turned roads red on Google Maps just by walking around.

Nice.

-

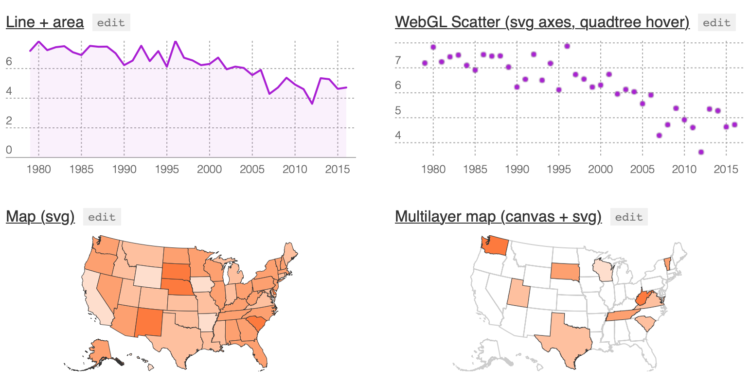

Michael Keller released a new version of Layer Cake:

Layer Cake is a graphics framework built on top of Svelte. It measures your target div and your data and creates scales that stay synced on layout changes. Use these scales to organize multiple, mostly-reusable Svelte components, whether they be SVG, HTML, Canvas or WebGL. Since they all share the same coordinate space, you can build your graphic one layer at a time.

I’m intrigued. (And I feel like I need to learn more about this Svelte.)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)