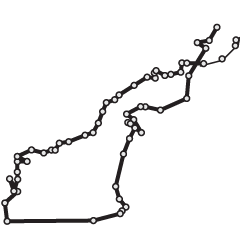

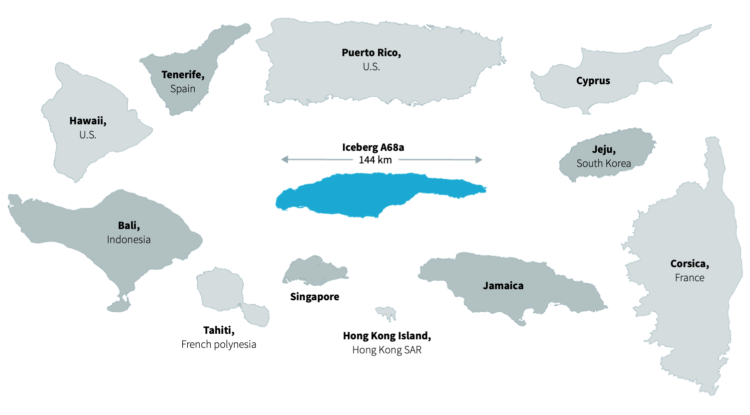

The world’s biggest iceberg, A68a, is on track to crash into a remote island in the Atlantic. For Reuters, Marco Hernandez and Cassandra Garrison show the path, the scale, and what might happen with A68a:

The iceberg is comparable in size to many well-known islands. A68a is very similar in size and shape to Jamaica, almost as long as the U.S. territory Puerto Rico, and dwarfs China’s Hong Kong Island as well as the Southeast Asian city state of Singapore.

Observers from the British Antarctic Survey told media that a flight last year over the A68a took about one and a half hours. The berg is so big, Royal Air Force pilots this week were unable to capture it all in one, single photograph.

Talking about the effectiveness of masks on TikTok,

Talking about the effectiveness of masks on TikTok,

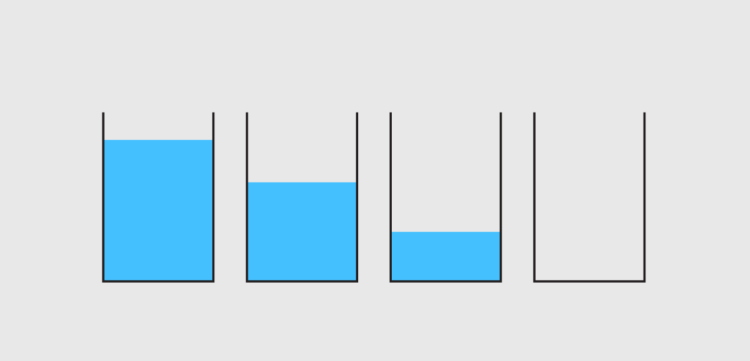

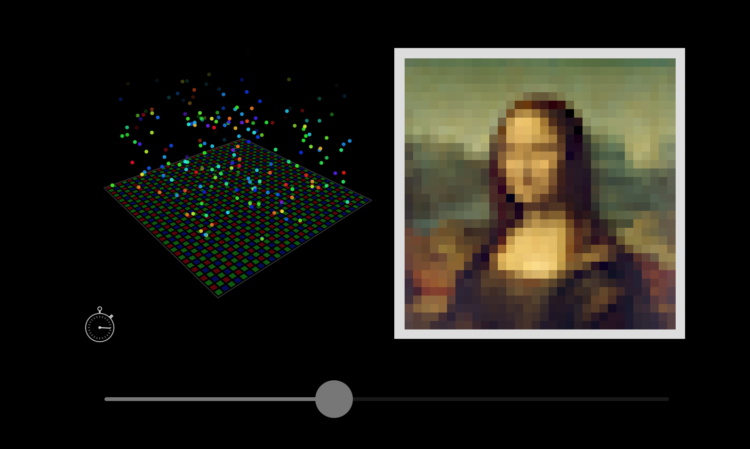

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)