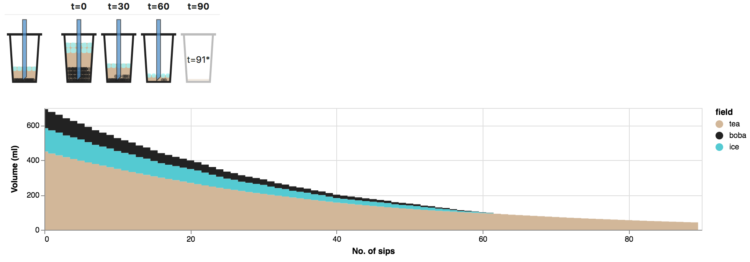

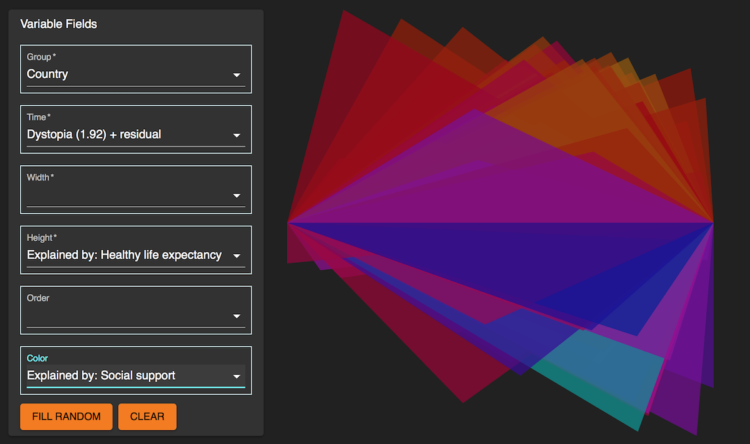

When you drink bubble tea, ideally you’d like to finish with the same proportions of boba and tea that you started at. Krist Wongsuphasawat took care of the math and provides a simulator for this ever important challenge:

This article simulates an optimized sip based on amount of boba and tea in the straw before sipping (method adopted from this post). The simulation assumes that all bobas sit in the bottom of the cup and stack on top of each other nicely. If you put a straw straight down when there are n layers of bobas, you will get n bobas in the straw. The rest of the straw up to the drink’s height is tea. The drinker sips until all n bobas are in his/her mouth then stop. After each sip these n bobas and tea inside the straw are gradually reduced from the cup.

The final recommendations: use a slim cup, minimize ice, and drink strongly. Mess around with variables here.

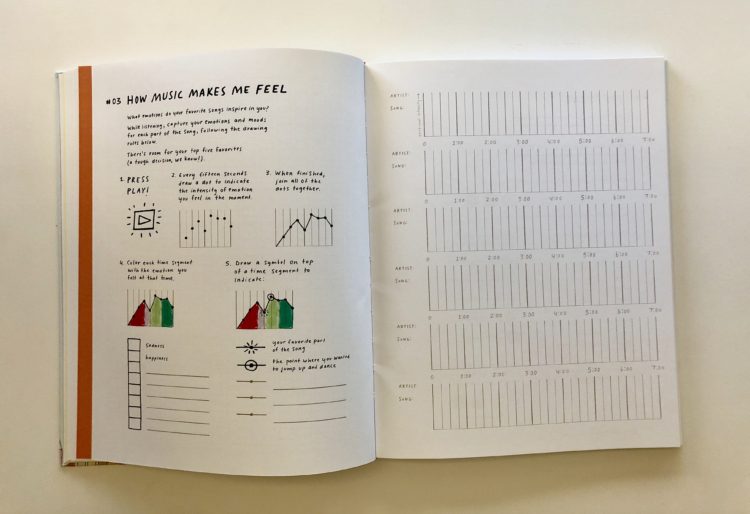

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)