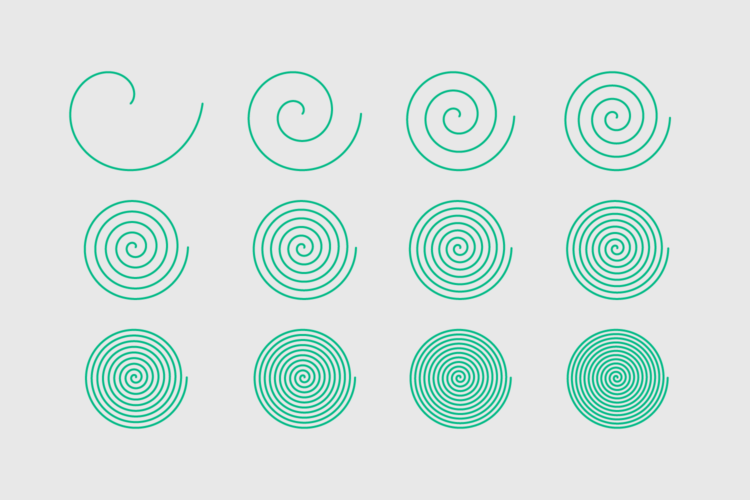

Manuel Lima goes into the history of the pie chart, or rather, circle representations in general. Despite many people poo-pooing the chart type over the decades, it keeps hanging around:

We might think of the pie chart as a fairly recent invention, with arguably more flaws than benefits, in regards to the statistical portrayal of data. However, if we look deep into history we realize this popular chart is only a recent manifestation of an ancient visual motif that carried meaning to numerous civilizations over space and time. A graphical construct of radiating lines enclosed by a circle, this motif is also a powerful perceptual recipe. If we look deep into ourselves we uncover a strong proclivity for such a visual pattern, despite the final message it might carry. As one of the oldest archetypes of the circular diagram, the sectioned circle will certainly outlast all of us, and indifferent to criticism, I suspect, so will the pie chart.

Yep.

Lima wrote a whole book on the use of circles in information design, in case you’re feeling yourself drawn to the shape for some unexplained reason.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)