I don’t know about you, but I like my bagel as two roughly cut, congruent linked halves. I usually use a fork, aluminum foil, and some duct tape. No more. George Hart demonstrates a better way to do it. It’s a good thing too, because I was running low on duct tape.

-

Statistics has an image problem. To the general public, it’s old, out of touch, and boring. It’s a problem because we place stock in a younger generation who we (1) want to be more data literate and (2) eventually lead the way, or at least participate, in all data-related realms. It’s beneficial for everyone.

This is Statistics is a new push by the American Statistical Association to provide a new perspective that doesn’t dwell on sheets of equations.

Read More -

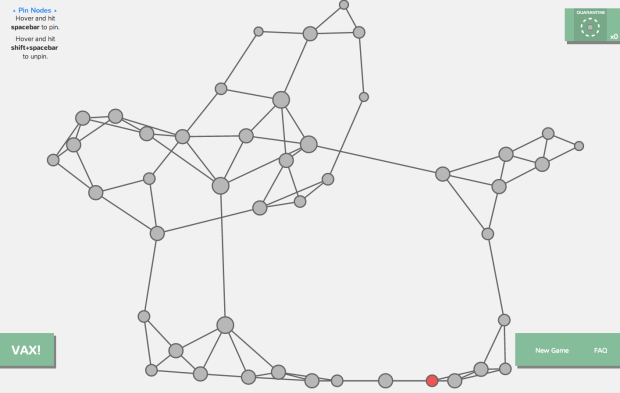

Vax, a game by Ellsworth Campbell and Isaac Bromley, explores how a disease spreads through a network, starting with just one infected person. It’s a simple concept that works well.

When you start the game, you have a network of uninfected people. The more connected a person is, the more chances that person can infect others upon his or her own infection. Your goal is to strategically administer a limited supply of vaccinations and to quarantine people to prevent as many infections as you can.

Fun and educational. Woo.

-

A new data source gave rise to a different set of visualization projects. We see people.

-

Lazaro Gamio and Richard Johnson for the Washington Post cover civilian deaths in the recent Gaza conflict, namely child civilians. Red icons represent children.

Similar to a previous piece on the death penalty in the United States, the icons provide more focus on individuals while maintaining a zoomed out view of the situation. However, this piece brings an interactive component that shows deaths over time and more information in tooltips on the mouseover.

-

All Things Considered on NPR ran a fine series on how we interpret probability and uncertainty. It came in five bits (plus one follow-up), each five to ten minutes long. They explore explanations of risk in different areas such as national security, health, and the daily weather and how people interpret the numbers and words.

A recurring theme was experts who use alternative descriptions for the seemingly concrete numbers.

Doctors, including Leigh Simmons, typically prefer words. Simmons is an internist and part of a group practice that provides primary care at Mass General. “As doctors we tend to often use words like, ‘very small risk,’ ‘very unlikely,’ ‘very rare,’ ‘very likely,’ ‘high risk,’ ” she says.

Not that words always makes understanding numeric probability easier. From the social scientist for the National Weather Service:

And it’s not just a numbers game — words used to describe weather can be just as confusing. Take “watch” and “warning,” for example.

“‘Watch’ means that conditions are ripe for something to happen. ‘Warning’ means that it is happening — it is imminent,” Brown says. “It’s easy to get them confused.”

Both the doctor and the social scientist agree that a combination of numbers, words, and a visual explanation could be the best route.

Some people think we should forgo trying to explain uncertainty to a general public that doesn’t understand, but the rejectors themselves don’t recognize the importance. Just because you don’t understand something doesn’t mean you should ignore it.

-

Numbers is a short film by Robert Hloz where some people see numbers appear above others’ heads. What the numbers are varies by the person with the ability, and it turns out knowing can be a blessing and a curse. Worth your nine and a half minutes of undivided attention:

-

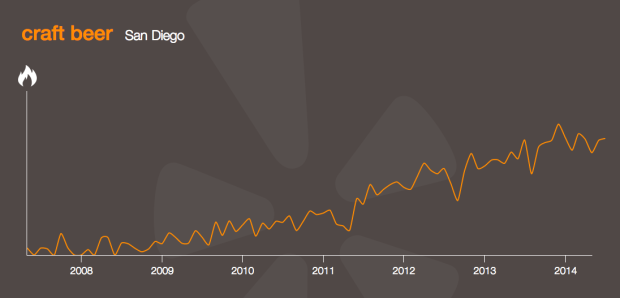

Yelp released an amusing tool that lets you see how the use of word in reviews has changed over the site’s decade of existence.

From food trends to popular slang to short-lived beauty fads (Brazilian blowout anyone?), Yelp Trends searches through words used in Yelp reviews to show you what’s hot and reveals the trend-setting cities that kicked it all off. Our massive wealth of data and the high quality reviews contributed by the Yelp community are what allow us to surface consumer trends and behavior based on ten years of experiences shared by locals around the world.

Just type in keywords, select your city, business category, and click the search button to see the changes. For the less used words, the data looks mostly like noise, but there are also some clear trends like in craft beer and chicken and waffles.

-

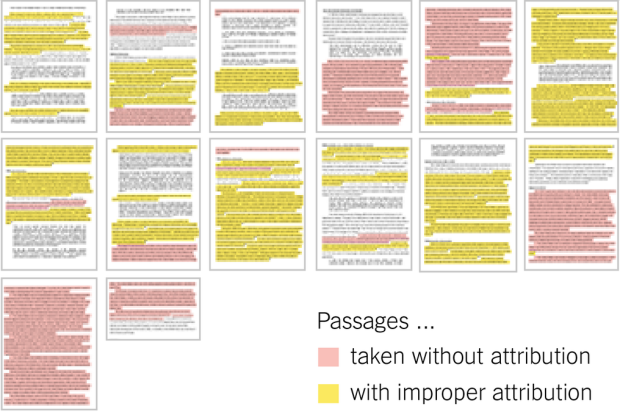

John Walsh, the U.S. Senator from Montana, is in the news lately for plagiarizing a large portion of his final paper towards his master’s degree. The New York Times highlighted the portions that Walsh copied without attribution (red) and the portions he copied with improper attribution (yellow). About a third of the paper was just straight up lifted from others’ works, including the final recommendations and conclusion, which is basically the grand finale.

See also: Visualizing Plagiarism by Gregor Aisch, which shows the plagiarized PhD thesis of Germany’s former Minister of Defense.

-

One of the most annoying parts of downloading data from large portals is that you never quite know what you’re gonna get. It’s a box of chocolates. It’s government data sites. It’s lists of datasets with vague or unhelpful titles with links to download. Of course, I’d rather have a hodgepodge than nothing at all, but as with most things, there’s room for improvement.

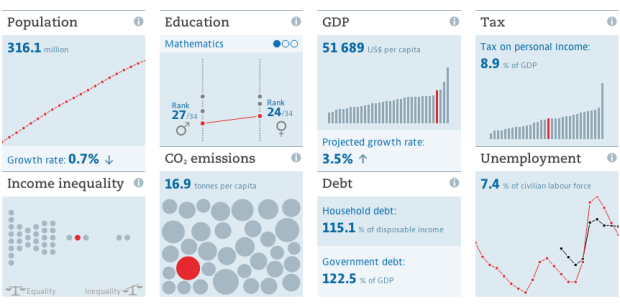

The OECD, which maintains and provides data on the country level, takes steps towards a more helpful portal that makes data grabs less of a headache. With the help of Raureif, 9elements, and Moritz Stefaner, the new portal is still in beta, but there’s plenty to like.

Read More -

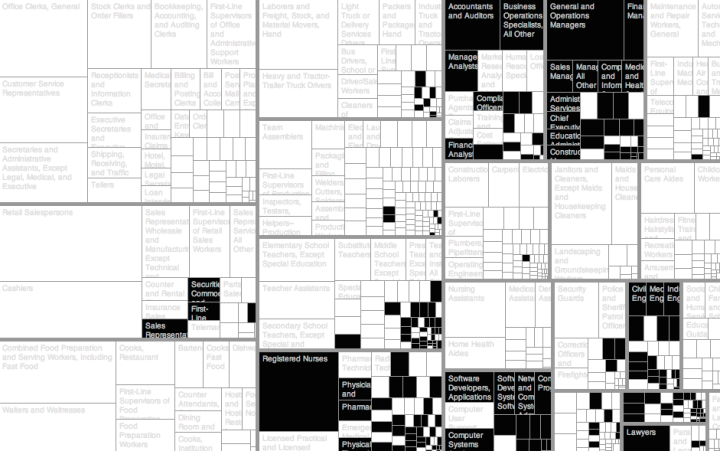

How to Make an Interactive Treemap

Treemaps are useful to view and explore hierarchical data. Interaction can help you look at the data in greater detail.

-

If you’ve played around with R enough, there comes a time when you just need some data to mess around with. Maybe it’s to learn a new method or to make one of your own. R offers some small-ish, clean datasets to poke at, but sometimes you need bigger, messier data. Hadley Wickham from RStudio released four popular large-ish datasets in package form to help you with that.

I’ve released four new data packages to CRAN: babynames, fueleconomy, nasaweather and nycflights13. The goal of these packages is to provide some interesting, and relatively large, datasets to demonstrate various data analysis challenges in R. The package source code (on github, linked above) is fully reproducible so that you can see some data tidying in action, or make your own modifications to the data.

Good.

-

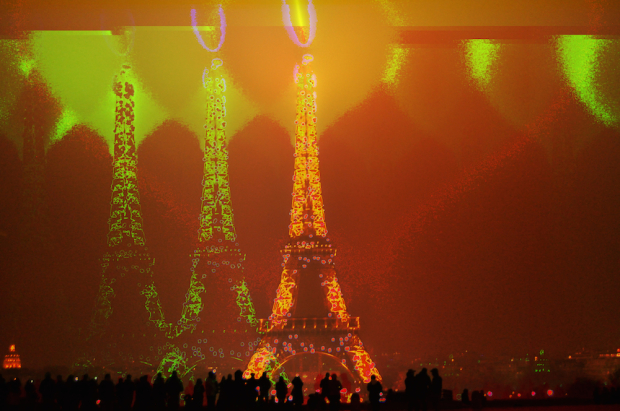

Masuma Ahuja and Denise Lu for the Washington Post applied a technique called databending to a bunch of photos. The idea is that computer files — even though they represent different things like documents, images, and audio — encode data in one form or another. It’s just that sound files encode beats, notes, and rhythms, whereas image files encode hue, saturation, and brightness. So when you treat image files as if they were audio, you get some interesting results.

See Jamie Boulton’s post from a couple of years ago for a detailed description on how to do this yourself with Audacity Effects.

-

From a couple of years ago, but still relevant, I think. Matthew Epler took candidate approval ratings (again, this is from a little while ago), tossed them in a 3-D program, made the molds to match, and poured in some silicon. Boom. Butt plugs that represent data. It’s called Grand Old Party.

Epler describes his project best:

Grand Old Party demonstrates that as a people united, our opinion has real volume. When we approve of a candidate, they swell with power. When we deem them unworthy, they are diminished and left hanging in the wind. We guard the gate! It opens and closes at our will. How wide is up to us.

So true.

-

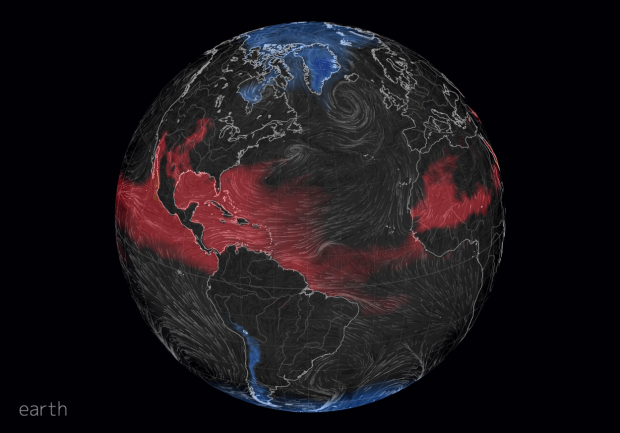

Late last year, Cameron Beccario made a wind map for earth, inspired by an earlier work by Fernanda Viegas and Martin Wattenberg. Beccario has been slowly adding overlays to the piece to show more dimensions of weather data around the world. The most recent overlay is what he calls a Misery Index, which is based on perceived air temperature.

If you’ve seen the interactive globe already, it’s worth revisiting. Click on the earth label on the bottom left to see the new stuff.

-

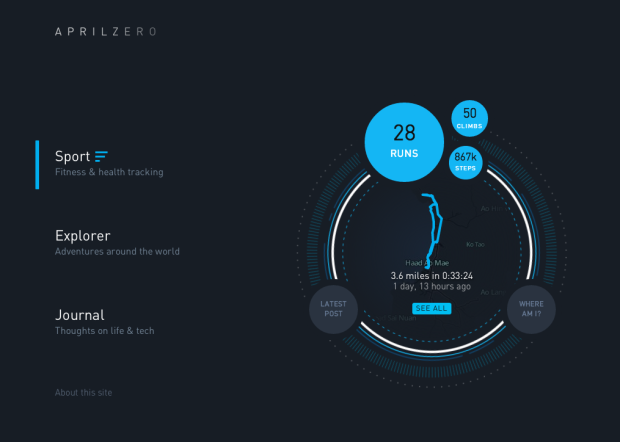

Personal data collection keeps getting easier and more efficient. Much of what was manual or clunky a few years ago is now automatic, done via the phone we carry every day anyway. More recently, personal data is finding a way out of the closed networks and applications and on to our own computers and servers.

Anand Sharma’s personal site is the newest example of what an individual can do with his or her own data. On a whim a few months ago, Sharma downloaded the Moves app, which tracks your location, and was hooked. Then with some design inspiration from Tony Stark, Sharma put a site together to show a feed a several aspects of his life, mostly tracked with his phone.

Read More -

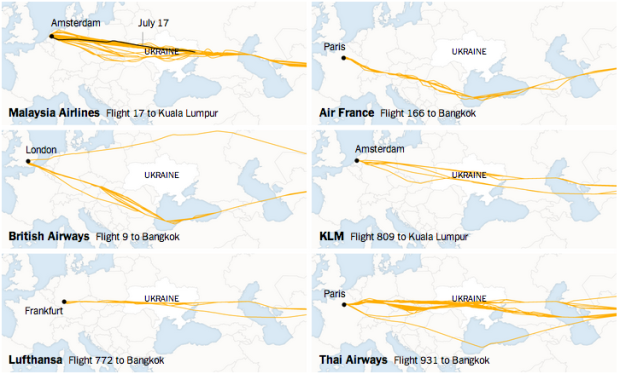

The New York Times is covering Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 with a series of maps. The ones above show a sample of recent flights in the area. Some airlines, such as British Airways and Air France show a clear path around Ukraine, whereas others take a more direct route.

-

LeBron James decided to head back to Cleveland, so naturally the odds that they win the championship went up. Todd Schneider charted the betting odds as the announcement happened to see how much they went up.

Of course that 10% already had built in some likelihood that James would choose to play for the Cavaliers next season. Before Cleveland was considered a threat to land LeBron, their championship odds were around 2%, so the 10% Cleveland odds immediately before LeBron’s decision perhaps reflected market expectations that LeBron had a 50% chance of choosing Cleveland: 0.5 * 0.18 + 0.5 * 0.02 = 0.1

Houston, who was expected to pick up Chris Bosh if James went to Cleveland, also saw a spike during the announcement, but the odds quickly came back down once Bosh decided to re-sign with Miami.

-

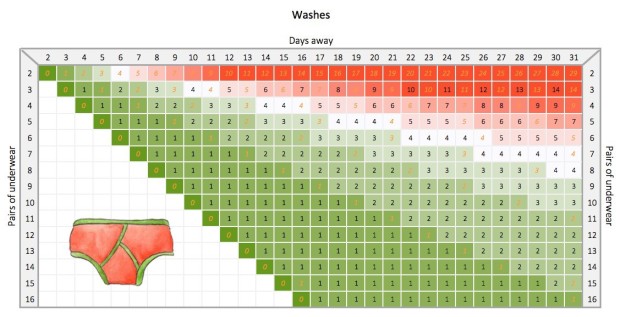

Packing underwear for a short trip is easy. You just pack a pair for each day you’re away. However, longer trips require extra planning. Pack a pair for every day, and you get a bag that’s too heavy. Pack too few and you have to launder your dirties more often.

Reed Kennedy and Carrie Smith gave this problem some extra thought, in search for the ideal underwear count, given the number of days you leave. The result is the chart above.

Simply select your trip length on the top, and then move down to find your ideal underwear count. The numbers inside the grid cells indicate how many times you have to launder. Gold numbers indicate a perfect remainder of zero pairs of clean underwear by the time you get home.

Note: This chart assumes you do not turn your underwear inside out for another wearing. Not that’d I’ve ever done that.

See the full post for further dirty underwear details.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)