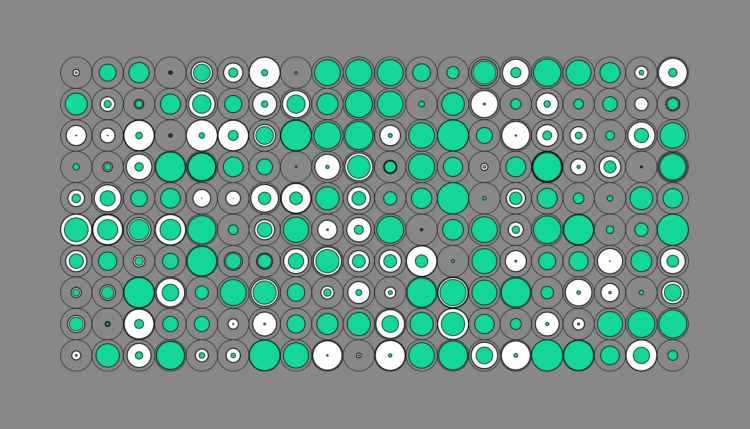

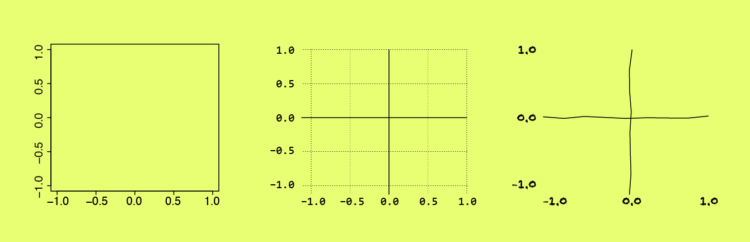

During a game, the range of emotions can vary widely across a crowd. Will Hipson, making use of some emotion dynamics, simulated how that range can change through a game:

What I’m striving to simulate are the laws of emotion dynamics (Kuppens & Verduyn, 2017). Emotions change from moment to moment, but there’s also some stability from one moment to the next. Apart from when a basket is scored, most fans cluster around a particular state (this is called an attractor state). Any change is attributable to random fluctuations (e.g., one fan spills some of their beer, maybe another fan sees an amusing picture of a cat on their phone). When a basket is scored, this causes a temporary fluctuation away from the attractor state, after which people resort back to their attractor.

I want to simulate emotion dynamics for all the things now.

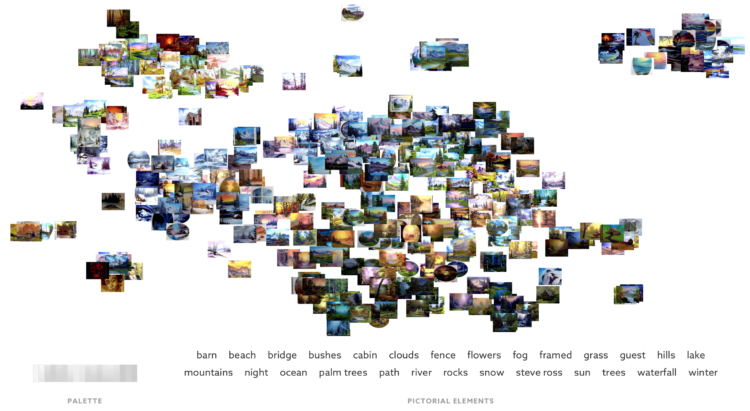

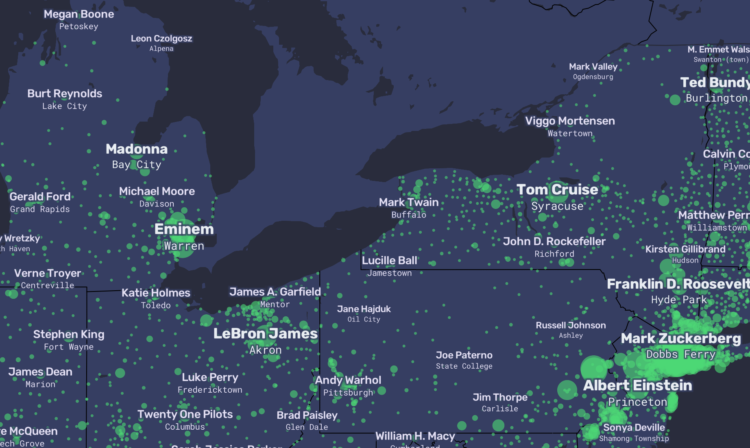

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)