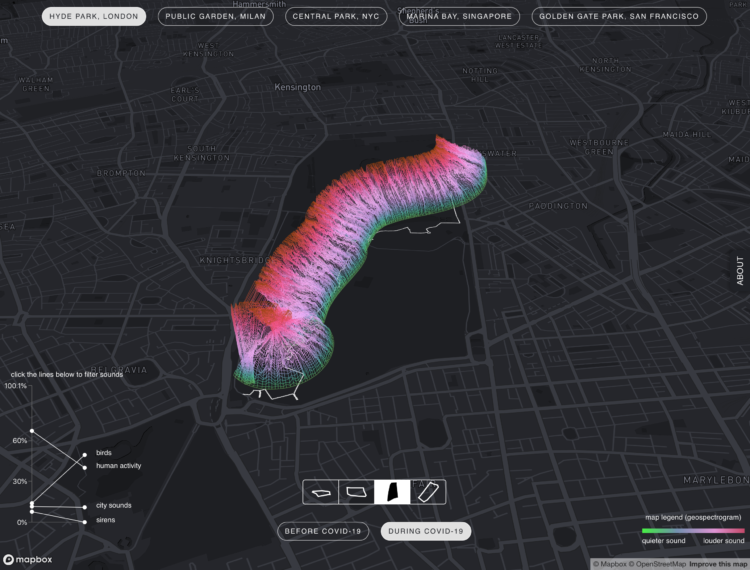

With lockdown orders arounds the world, places that we’re allowed to go sound different. The MIT Senseable City Lab looked at this shift in audio footprint through the lens of public parks:

Using machine learning techniques, we analyze the audio from walks taken in key parks around the world to recognize changes in sounds like human voices, emergency sirens, street music, sounds of nature (i.e., bird song, insects), dogs barking, and ambient city noise. We extracted audio files from YouTube videos of park walks from previous years, and compared them with walks recorded by volunteers along the same path during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis suggests an overall increase in birdsong and a decrease in city sounds, such as cars driving by, or construction work. The interactive visualization proposed in Sonic Cities allows users to explore and experience the changing soundscapes of urban parks.

The 3-D view shown above is visually interesting, but the top-down view is the easiest to read, looking like a stacked area chart over a map.

At distinct points on the mapped paths, a gradient line represents the distribution of quieter and louder sounds. Louder sounds appear to take up more space during the pandemic.

It’s hard to say how accurate the sound classification is through this view, but as I poked around, it seemed a bit rough. For example, the chart for Central Park in New York shows bird sounds making about 0% of the footprint, but you can hear birds pretty easily in the audio clips. I’d also be interested in how they normalized between YouTube clips and their own recorded audio to get a fair comparison.

Nevertheless, it’s an interesting experiment both statistically and visually. Worth a look.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)