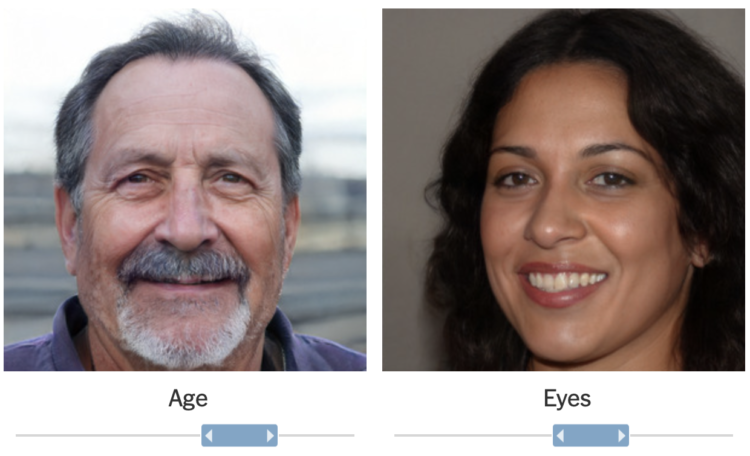

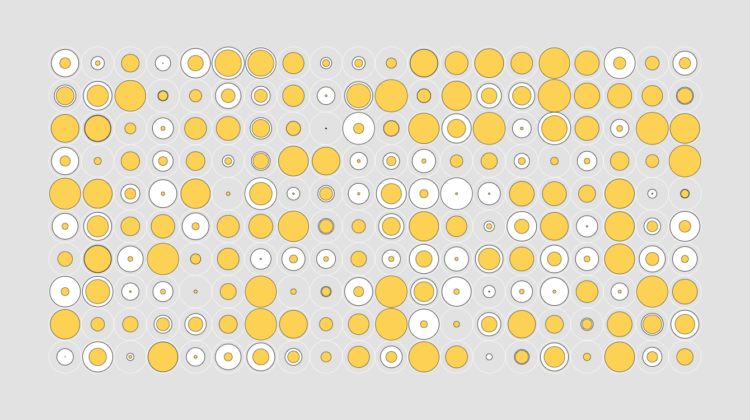

It’s grown easier and easier to generate fake faces with AI. For The New York Times, Kashmir Hill and Jeremy White demonstrate the tech with a slick interactive. Quickly adjust age, eye, mood, and gender. All fake.

It was only a few years ago when the idea seemed novel. One year later, there were guides (and warnings) for spotting fake faces. By 2019, there was a marketplace for fake faces (of course). Sometimes it’s scary to think about what the internet will be in five years.

In any case, check out the NYT piece. The smooth transitions between faces, one facial aspect at a time, is mesmerizing.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)