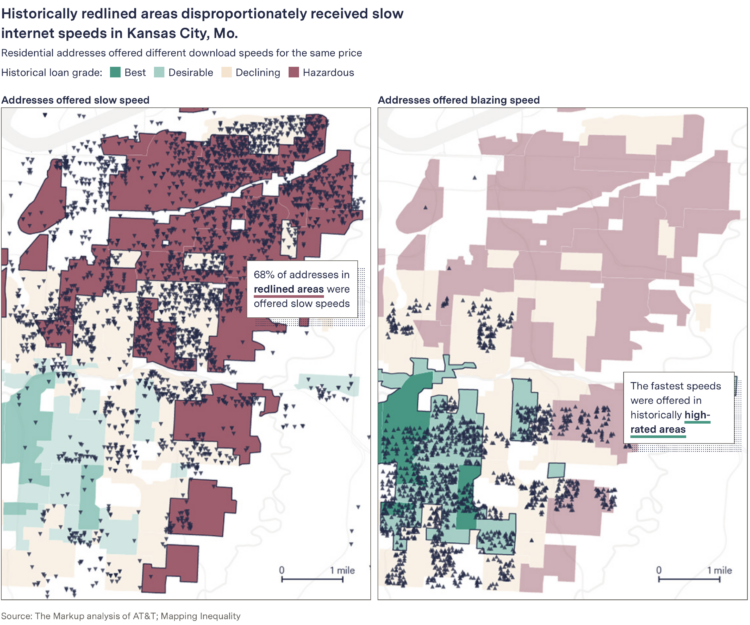

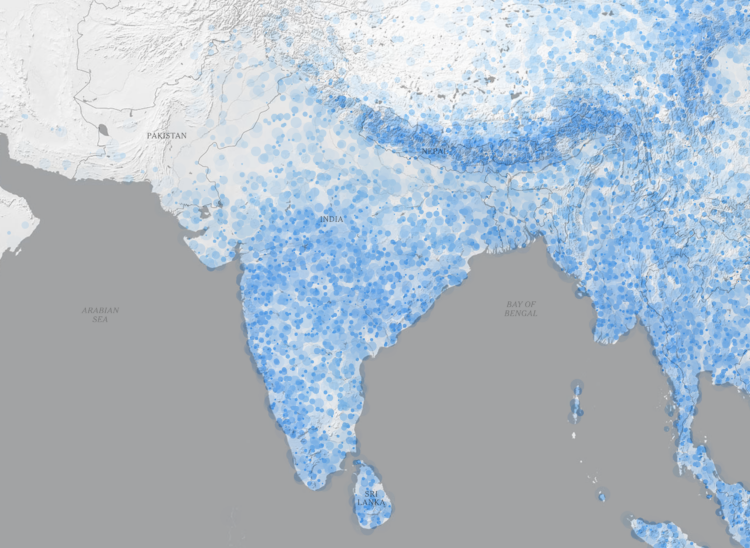

When you pay for internet, it seems like a reasonable expectation that if you pay the same monthly rate as someone a few blocks from you, you get a similar speed. This is commonly not always the case. Leon Yin and Aaron Sankin, for The Markup, with the analysis:

The Markup gathered and analyzed more than 800,000 internet service offers from AT&T, Verizon, Earthlink, and CenturyLink in 38 cities across America and found that all four routinely offered fast base speeds at or above 200 Mbps in some neighborhoods for the same price as connections below 25 Mbps in others.

The neighborhoods offered the worst deals had lower median incomes in nine out of 10 cities in the analysis. In two-thirds of the cities where The Markup had enough data to compare, the providers gave the worst offers to the least-White neighborhoods.

When you compare by Mbps per dollar, you get prices hundreds of times more expensive for crawling internet.

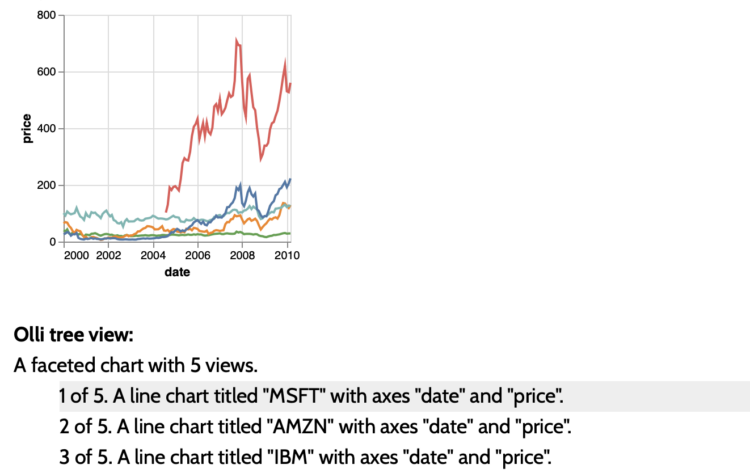

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)