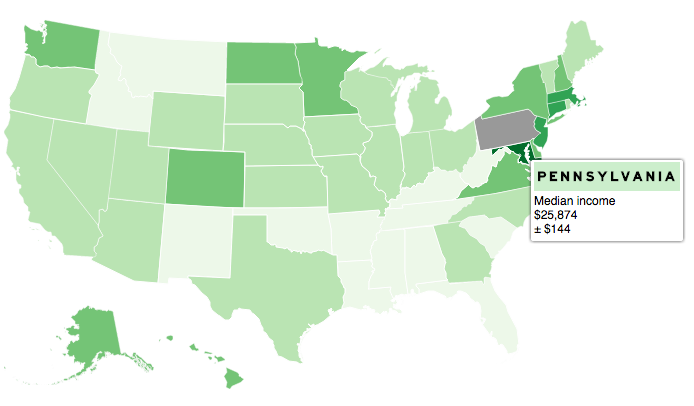

Despite the frequent use of choropleth maps online, they’re still kind of tricky to produce for beginners. Landline, an open source JavaScript library from ProPublica, aims to make it a little bit easier. Given a GeoJSON file, Landline provides an interactive choropleth map with tooltips that works on multiple devices.

Still in its early stages, the library lets you make state and county maps, as well as customize to your own needs. Underscore.js and Raphael.js are its two dependencies, so it plays nice with those libraries also.

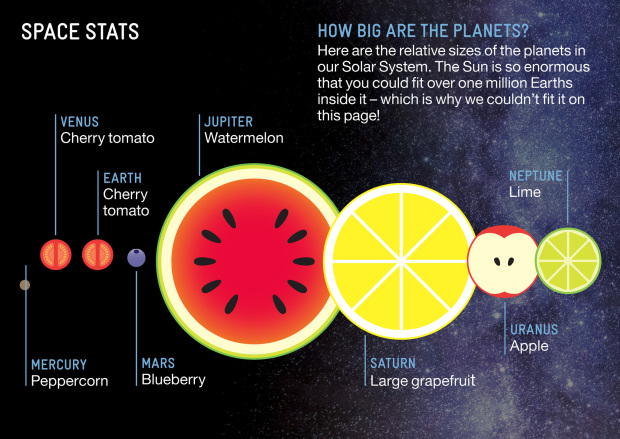

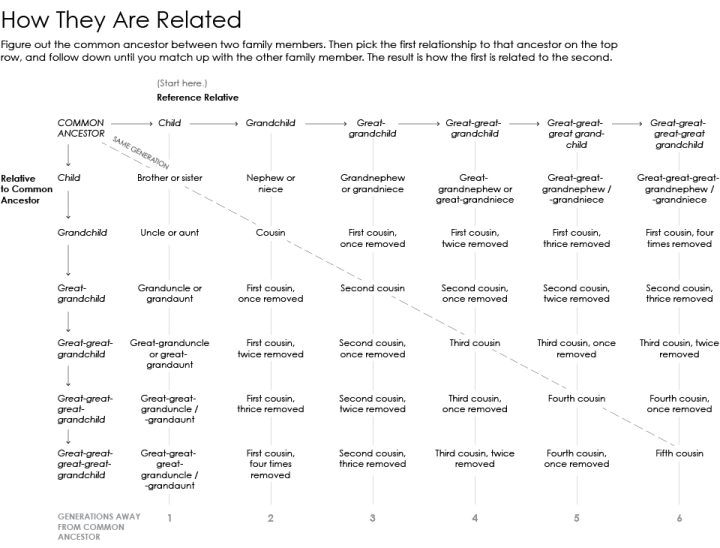

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)