Gestalt refers to our ability to see a whole from the parts, and it’s why visualization works. Otherwise, we wouldn’t see patterns (or lack of them).

Gestalt refers to our ability to see a whole from the parts, and it’s why visualization works. Otherwise, we wouldn’t see patterns (or lack of them).

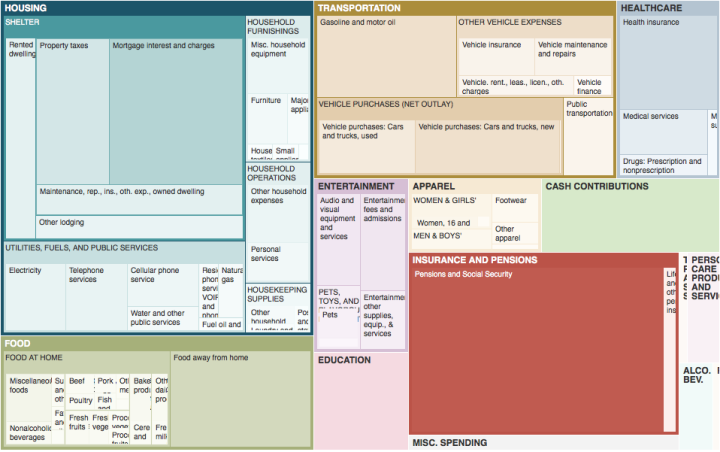

Elijah Meeks describes some of the principles — similarity, proximity, and enclosure — in a quick demo used in a recent talk. Meeks argues, “Effective design and implementation of more complex data visualization that relies on enclosure (like treemaps and circle packing) and other gestalt principles not covered in this short essay can only happen if you are aware of the signals those graphics are sending.” Otherwise, you might show something completely different, unintentionally.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)