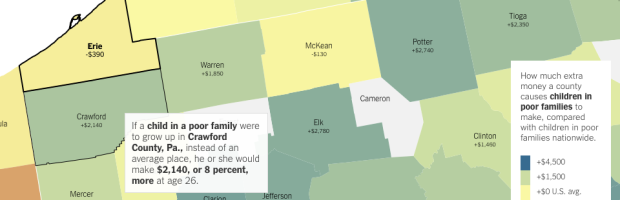

Wyoming just passed a law that makes it illegal to collect data about the environment, if you intend to send it to a federal or state government agency.

The reason? The state wants to conceal the fact that many of its streams are contaminated by E. coli bacteria, strains of which can cause serious health problems, even death. A small organization called Western Watersheds Project (which I represent pro bono in an unrelated lawsuit) has found the bacteria in a number of streams crossing federal land in concentrations that violate water quality standards under the federal Clean Water Act. Rather than engaging in an honest public debate about the cause or extent of the problem, Wyoming prefers to pretend the problem doesn’t exist. And under the new law, the state threatens anyone who would challenge that belief by producing information to the contrary with a term in jail.

Um, wut?

The intent part confuses me most. So is it okay to collect environmental data that you don’t plan on sending to a government agency? If I were in Wyoming, I’d grab the nearest water kit, collect data water data like a fiend, and send it to my local paper, news outlet, or anywhere else that could publicize high concentrations of E. coli.

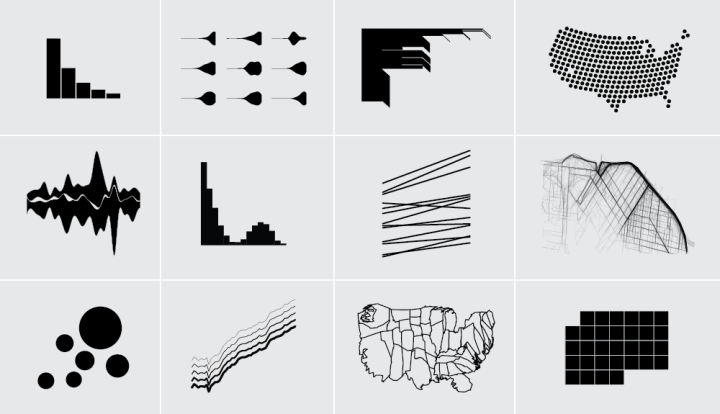

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)