Speaking of A.I. and fiction, Adam Epstein for Quartz reported on how Wattpad, the platform for people to share stories, uses machine learning to find potential movies:

Wattpad uses a machine-learning program called StoryDNA to scan all the stories on its platform and surface the ones that seem like candidates for TV or film development. It works on both macro and micro levels, analyzing big-picture audience engagement trends to identify the genres picking up steam, while also looking at the specific stories that got popular quickly and calculating what made them so appealing.

The tool can break stories down to their vocabularies and sentence structures (a story’s “DNA,” if you will) and then compare those to other stories to deduce what really makes a work of fiction popular. It also looks at how often users comment on stories and, when they do, what exactly they’re saying. Its goal is to examine all these clues to uncover the precise combination of story elements—genre, emotion, grammar, the list goes on—that hooks audiences to the point they’ll follow its journey onto a visual medium.

Maybe I’m just getting old, but this sounds terrible.

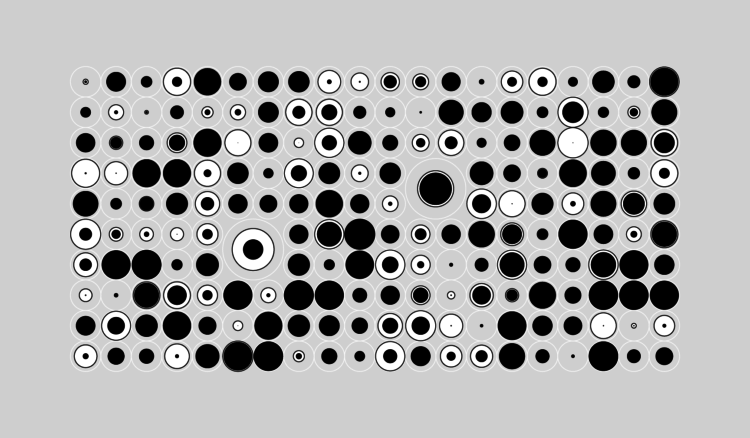

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)