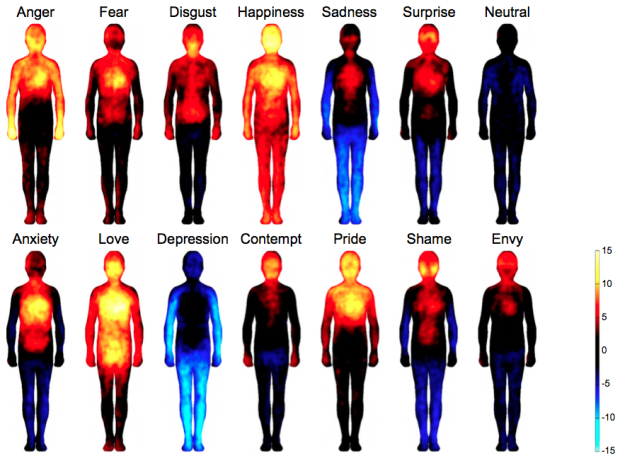

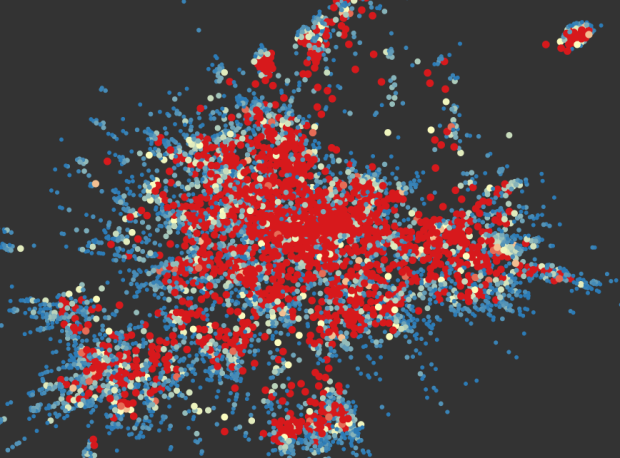

Engineering and psychology researchers in Finland investigated where we feel and don’t feel.

The team showed the volunteers two blank silhouettes of person on a screen and then told the subjects to think about one of 14 emotions: love, disgust, anger, pride, etc. The volunteers then painted areas of the body that felt stimulated by that emotion. On the second silhouette, they painted areas of the body that get deactivated during that emotion.

The body maps above show the results of the survey. As you’d expect, the body looks like it shuts down with depression, and it lights up with happiness, but it’s the subtle differences that are most interesting. I like the contrast between pride and anger, a difference of fists and feet.

Check out the full paper for more details. [via NPR]

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)