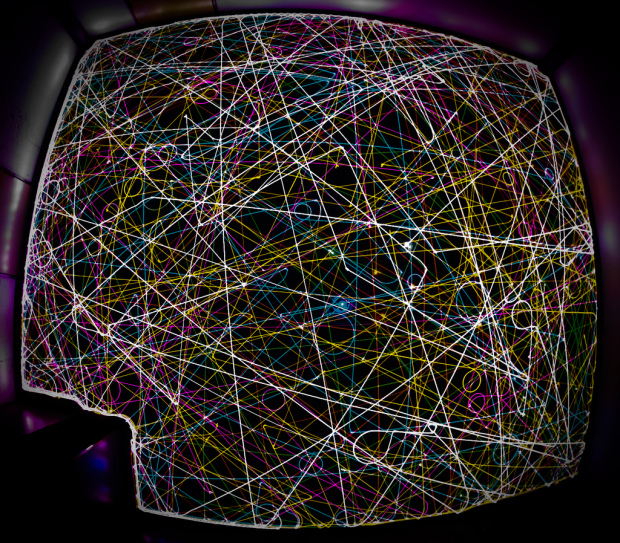

You’ve probably heard of the six degrees of Kevin Bacon. The idea is that you can name any actor and trace back to Kevin Bacon through actors who have worked together. Ben Blatt for Slate applied this idea to sports and put together an interactive that finds the number degrees between athletes. The fun part is that you can enter two athletes from different professional sports: basketball, football, and baseball.

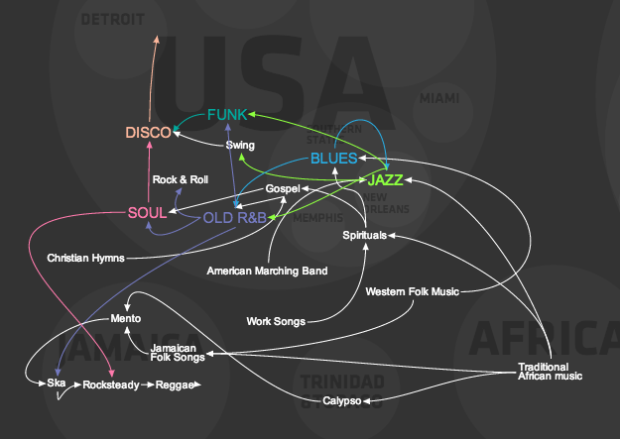

What’s even more remarkable is that it’s possible to connect players who didn’t even play the same sport. Cross-sport athletes like Deion Sanders and Bo Jackson are exceedingly rare, and some combinations of sports are hardly seen at all. Of these 18 athletes, all but one—Bud Grant—played baseball as one of his two pro careers, proving either that the stars of the diamond are athletic enough to master other sports or that anyone athletic enough to play basketball or football can also handle baseball. Hockey is the opposite, as there has never been a pro hockey player who also played top-level basketball, football, or baseball. As a result, hockey is a closed system. But once you get off the ice, it’s possible to link every pro baseball, basketball, and football star.

I like how it only takes 18 players (well, actually probably fewer) to pull double-time to make this possible. To link Yao Ming (basketball) and Joe Montana (football), it only took six hops, with Mark Hendrickson as a link between basketball and baseball and Deion Sanders as the link between baseball and football.

Surprising? Kind of, but then again, in 2011, almost all pairs of people on Facebook could be linked with just six hops, too. The barebones interactive is still a lot of fun to play with though if you follow sports.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)