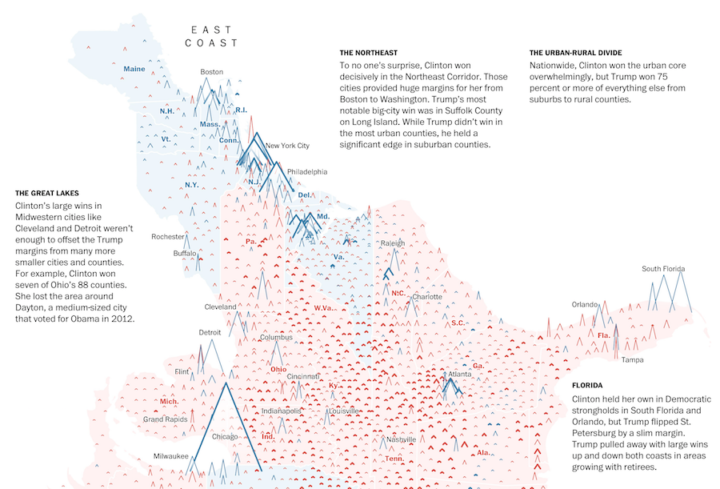

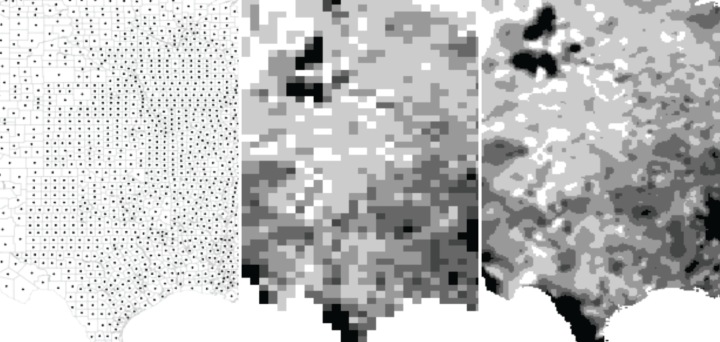

This is some fine map work by Lazaro Gamio and Dan Keating for the Washington Post. It shows total votes and margin of victory for each county with a peaks and valleys metaphor. Taller means more votes, and wider means greater margin. The Post rotated the United States map so that the east coast is on top and the west coast is on the bottom, which allows for scrollability and provides more space horizontally to show margins.

Nice.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)