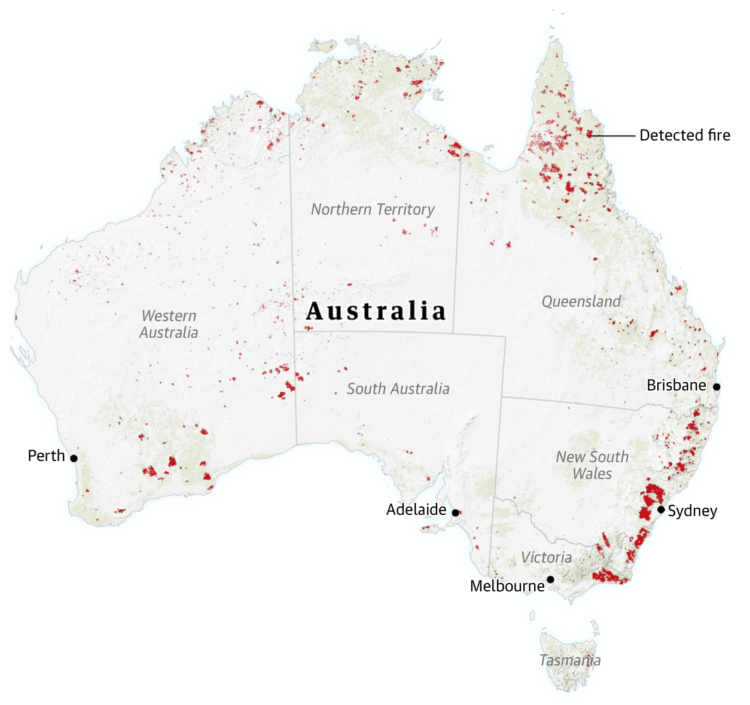

With all of the maps of fire in Australia, be sure to check out this piece by Georgina Rannard for BBC News on how some of the maps can easily be misinterpreted when seen out of context.

-

For The Guardian, Niko Kommenda and Josh Holder provide a visual guide to the bushfires in Australia:

Satellite data from Nasa showed a stark increase in the number of fire detections in November and December compared with previous years. Satellites detect fire “hotspots” by measuring the infrared radiation emitted by the blazes.

In previous years, between 2,000 and 3,000 such hotspots were recorded each December in the south-east, while in 2019 the number reached 227,000.

There’s an animated time series chart that changes the range of the y-axis, which I think is a good way to demonstrate the scale of the current fires.

-

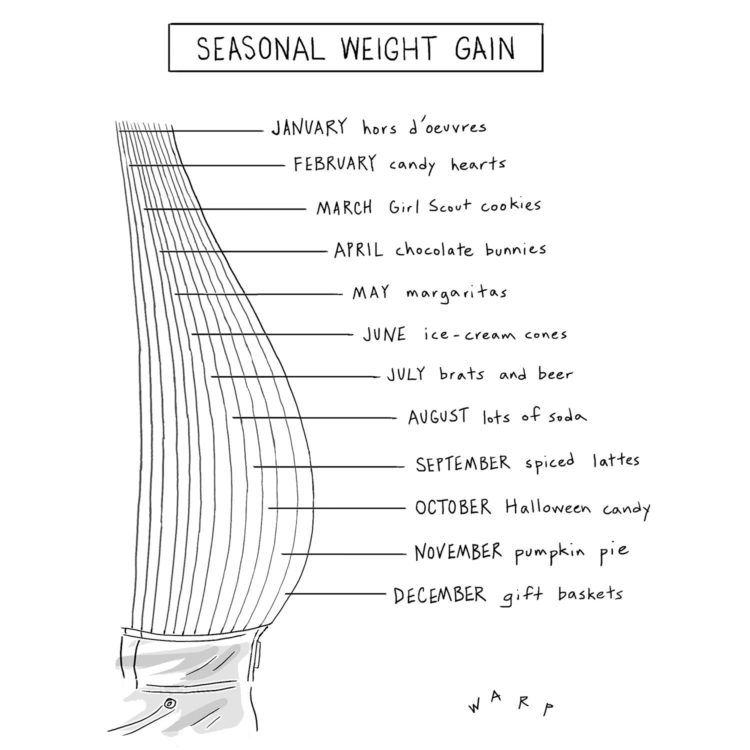

From Kim Warp for The New Yorker. Ha. Ha. It’s funny because it’s true.

It reminds me of Amanda Cox’s dress size graphic for the NYT.

[Thanks, Mike]

-

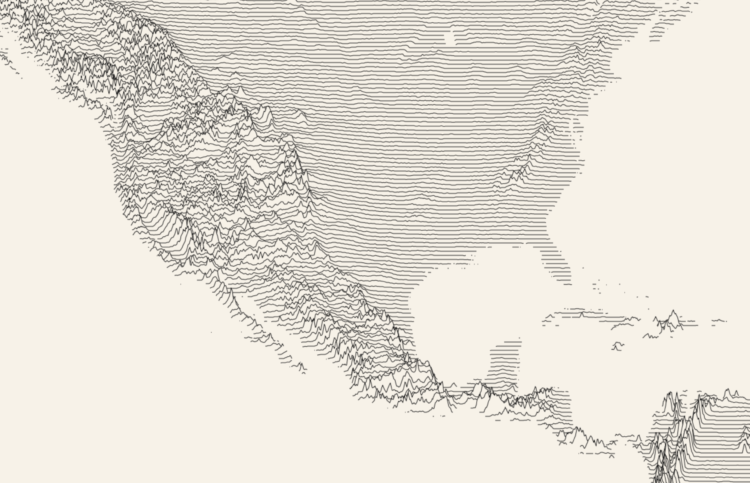

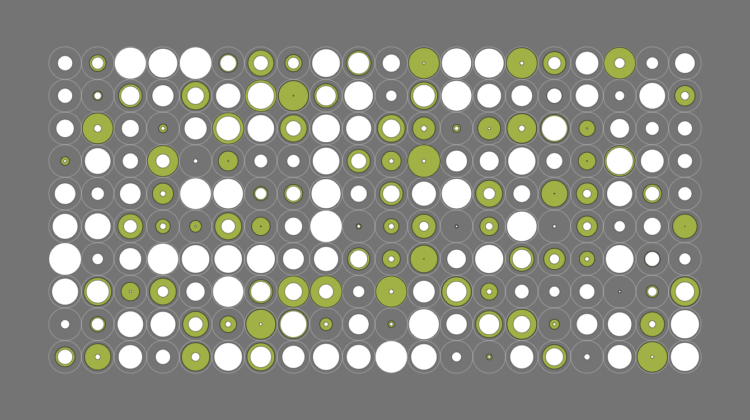

Ridgeline charts or frequency trails use parallel lines that overlap on the fluctuations, which creates a 3-D effect at the peaks. Andrei Kashcha used this method to show elevation around the world in an interactive map.

Click-and-drag to any location, and you get something like the above. You can also change parameters like maximum peaks, line density, and color. Even get your results printed on a mug.

Kashcha posted his code on GitHub.

See also James Cheshire’s population lines from 2014.

-

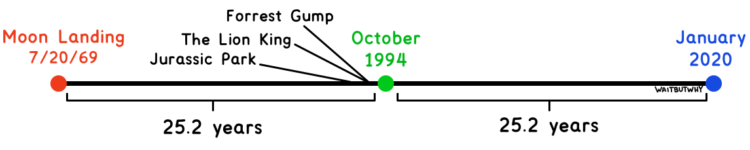

One of the best ways to feel old is to look to your past and realize how long ago it was. Wait Buy Why demonstrates with a bunch of timeline splits. For example: “Remember when Jurassic Park, The Lion King, and Forrest Gump came out in theaters? Closer to the moon landing than today.

I feel like there was an xkcd comic about this, but the closest I could find in my notes was a tweet from Neil deGrasse Tyson: “Just an FYI: The year 1980 is as far in today’s past as 1947 was to 1980.”

Update: From xkcd, there was one on Movie Ages and another on Timeghost. (Thanks, @ilarischeinin and @CultureOverTime.)

Yay. We’re all old. Eventually.

-

Members Only

-

For The Upshot, Emily Badger and Quoctrung Bui looked for major urban developments in the United States by comparing satellite imagery of past to present:

To grasp the scale of this decade of change, The Upshot worked with Tim Wallace and Krishna Karra from Descartes Labs, a geospatial analytics company, using a tool that has itself evolved significantly over this time: satellite imagery. With its growing power and precision, we can see both intimate details — a single home, bulldozed; a tennis court, reinvented — and big patterns that recur across the country. Here, we show some of the most consequential changes over the last 10 years, as seen from above.

The resolution is impressive (but still creeps me out a little bit). And while maybe not as fun to watch as a time-lapse, the two-snapshot treatment provides more contrast, which makes it easier to see the change. I also like the two small dots on the right of each image to indicate progress while scrolling.

-

My main goal for FD this year was to make charts.

I hoped to make one chart per week, along with the newsletter and tutorials, which would force me to focus and spend less time dwelling on a dataset. I didn’t quite get to one per week, but I made about twice as many graphics as I did last year. I’ll take it.

Instead of long-ish, in-depth analyses, I usually looked at one dataset from various angles, making one or two graphics per angle. Basically, instead of essays, I opted for small collections of short stories.

So, here are the most popular topics/datasets and their accompanying charts.

Read More -

A file leaked to The New York Times contained location traces of 12 million unique smartphones. Stuart A. Thompson and Charlie Warzel went digging:

The data set is large enough that it surely points to scandal and crime but our purpose wasn’t to dig up dirt. We wanted to document the risk of underregulated surveillance.

Watching dots move across a map sometimes revealed hints of faltering marriages, evidence of drug addiction, records of visits to psychological facilities.

Connecting a sanitized ping to an actual human in time and place could feel like reading someone else’s diary.

They also probably found the POTUS in the data.

Ugh.

-

The decade is almost done. You’re sitting there and you’re thinking: “I wish I could easily access the scripts from all seasons of The Office so that I could analyze the dialogue and relationships between characters.” Well, your wish is granted. Bradley Lindblad stuck all the scripts in an R package. It’s called schrute.

Take that, 2019.

-

For The New York Times, Jonah M. Kessel and Hiroko Tabuchi went to oilfields in Texas with an infrared camera to look for methane leaks.

Okay, important topic here, and the contrast between regular photograph and infrared video is alarming, but I may have been drawn to the methodology at the end:

To create images of methane emissions in the Permian Basin, The Times used a custom-built FLIR camera that converts infrared energy into an electronic signal to create moving pictures. The camera’s filter allows infrared wavelengths between 3.2 to 3.4 micrometers on the electromagnetic spectrum to pass through to the sensor.

To visualize gas, the camera uses helium to cool down the sensor to the temperature of liquid nitrogen, around minus 200 degrees Celsius. Unlike traditional photography lenses, which are glass, the infrared images were created using metal lenses made from germanium, which is transparent at infrared wavelengths.

-

One way to gauge the amount of ice in the Arctic is to look at the average age of the ice. From the NASA Scientific Visualization Studio, the map above shows the estimated age of ice on a monthly basis, going back to 1984:

One significant change in the Arctic region in recent years has been the rapid decline in perennial sea ice. Perennial sea ice, also known as multi-year ice, is the portion of the sea ice that survives the summer melt season. Perennial ice may have a life-span of nine years or more and represents the thickest component of the sea ice; perennial ice can grow up to four meters thick. By contrast, first year ice that grows during a single winter is generally at most two meters thick.

-

Pew Research Center analyzed online sermons in U.S. searches, taking a closer look at what people typically hear across religions:

For instance, the distinctive words (or sequences of words) that often appear in sermons delivered at historically black Protestant congregations include “powerful hand” and “hallelujah … come.” The latter phrase (which appears online in actual sentences such as “Hallelujah! Come on … let your praises loose!”) appeared in some form in the sermons of 22% of all historically black Protestant churches across the study period. And these congregations were eight times more likely than others to hear that phrase or a close variant. Although the word “hallelujah” is by no means unique to historically black Protestant services, this analysis indicates that it is a hallmark of black Protestant churches.

-

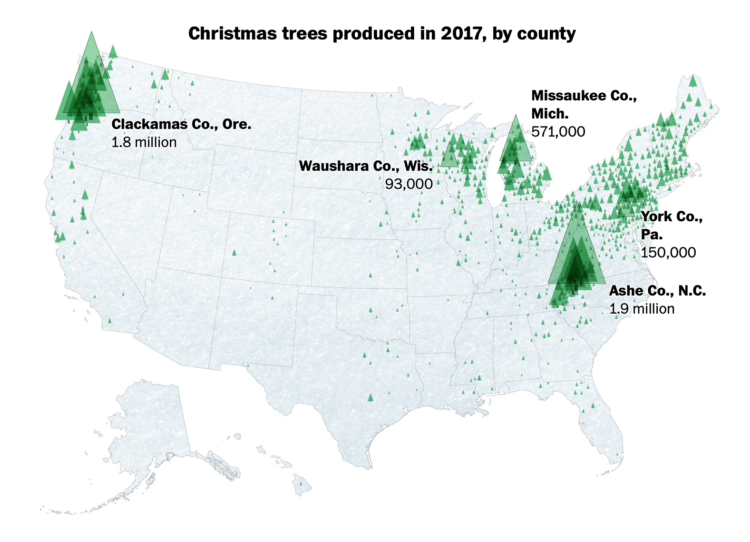

For The Washington Post, Tim Meko and Lauren Tierney:

Before the 1930s, Christmas trees typically were cut down on an individual’s property or out in the wild. Now, tree farms in all 50 states (yes, Hawaii too) are where most Christmas trees come from, accounting for 98 percent of live Christmas trees brought into homes. These farms churn out many kinds of conifers, but two main regions — Clackamas County near Portland, Ore., and the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina — produce the most.

I wonder if we can see a similar map for artificial Christmas trees.

-

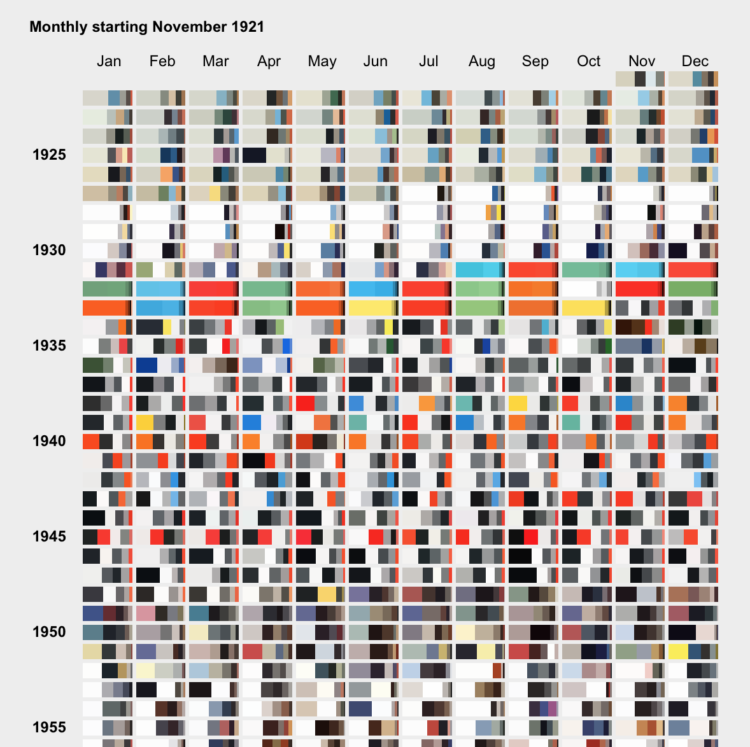

For Scientific American, Nicholas Rougeux and Jen Christiansen show the shift in hues for the magazine’s covers over the past 175 years. The changes serve as a proxy for technology advancements, changes in ownership, and shifts in thinking.

-

As I do every year, I picked my ten favorite visualization projects. Here they are in no particular order.

-

Members Only

-

Our brains are pretty good at finding patterns, but it has some blindspots and then we get confused. The Illusion of the Year contest targets those blindspots. This year’s winner shows a rotating pattern that seems to switch axes depending on where you look.

-

Standardized ratings are a challenge, because they often try to encapsulate many variables into a single variable. On the upside, a single score is quick and easy to see, but on the downside, variance goes into hiding and people/things that don’t fit a defined standard get dinged.

Vox looks at these challenges in the context of online school ratings.

-

By way of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, ProPublica and The Boston Globe requested records from each state. They compiled the many documents into a single dataset:

In each record, CAPTA requires states to list the age and gender of the child, and information about a household’s prior contact with welfare services. The information is supposed to help government agencies prevent child abuse, neglect and death, but reporting across states is so inconsistent that comparisons and trends are impossible to identify. ProPublica is releasing the data we’ve collected as a minimum count of child fatality records in the United States. Researchers and journalists can download the full records with summaries at the ProPublica Data Store.

Unfortunately, not all state agencies are compliant, but it’s a start.

Also, Jessica Huseman of ProPublica discussed some of the emotional challenges of working with such sensitive data.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)