This looks promising:

While it is often easy, and tempting, to write a scraper as a dirty one-off script, spatula makes an attempt to provide an easy framework that most scrapers fit within without additional overhead.

This reflects the reality that many scraper projects start small but grow quickly, so reaching for a heavyweight tool from the start often does not seem practical.

The initial overhead imposed by the framework should be as light as possible, providing benefits even for authors that do not wish to use every feature available to them.

Although, without my dirty one-off scripts, what will I put in my tmp data folder?

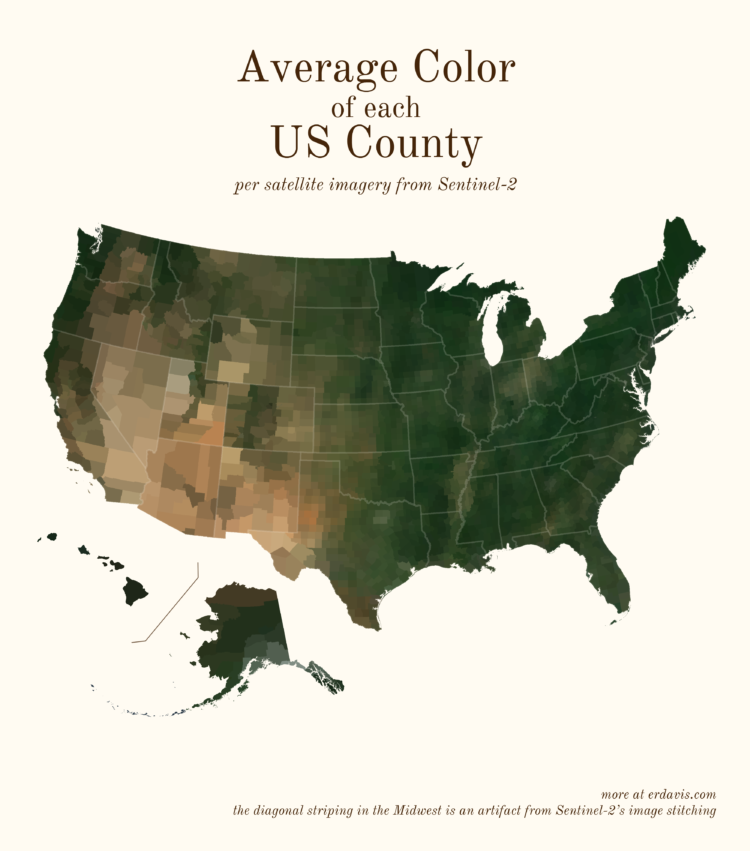

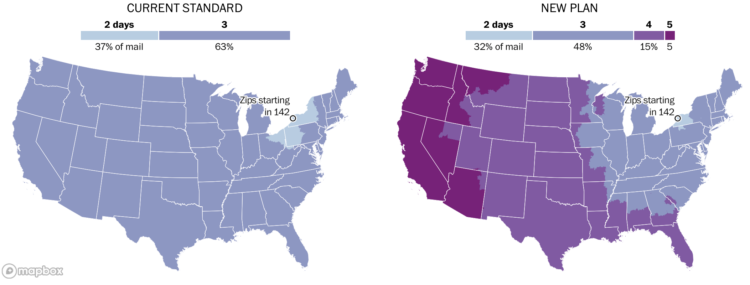

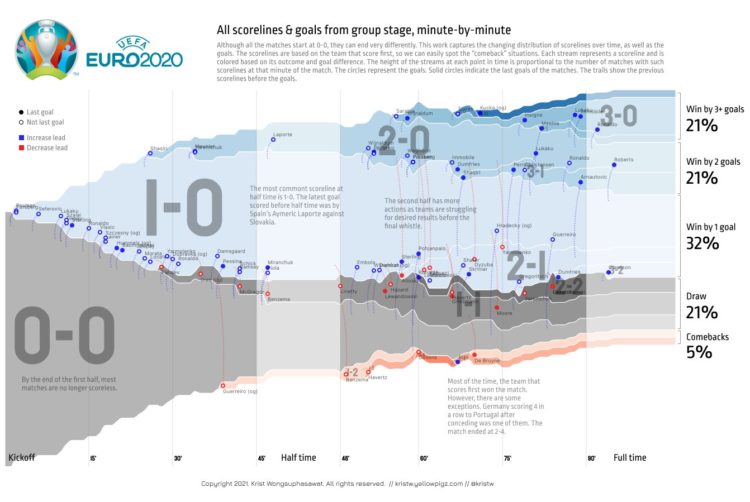

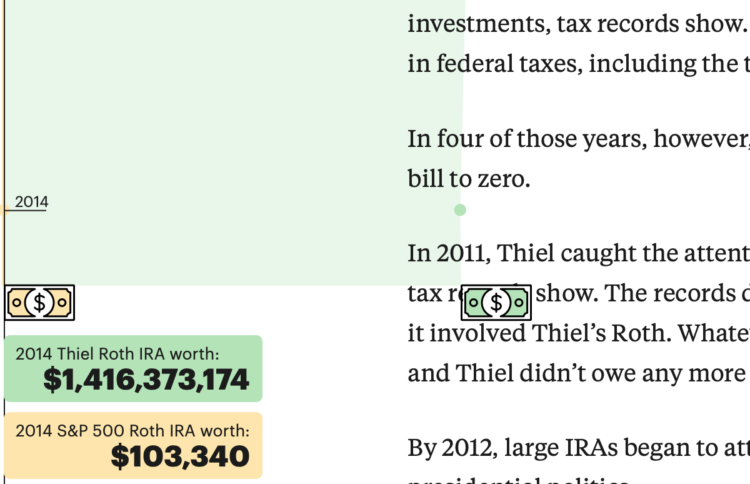

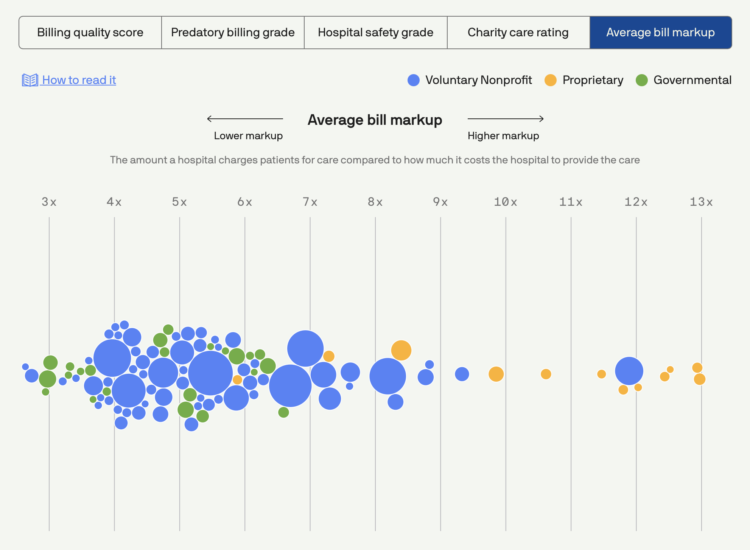

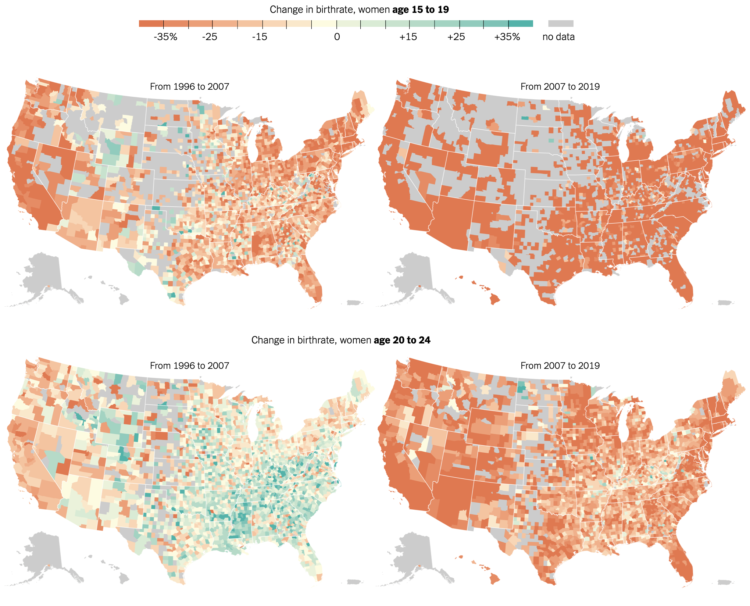

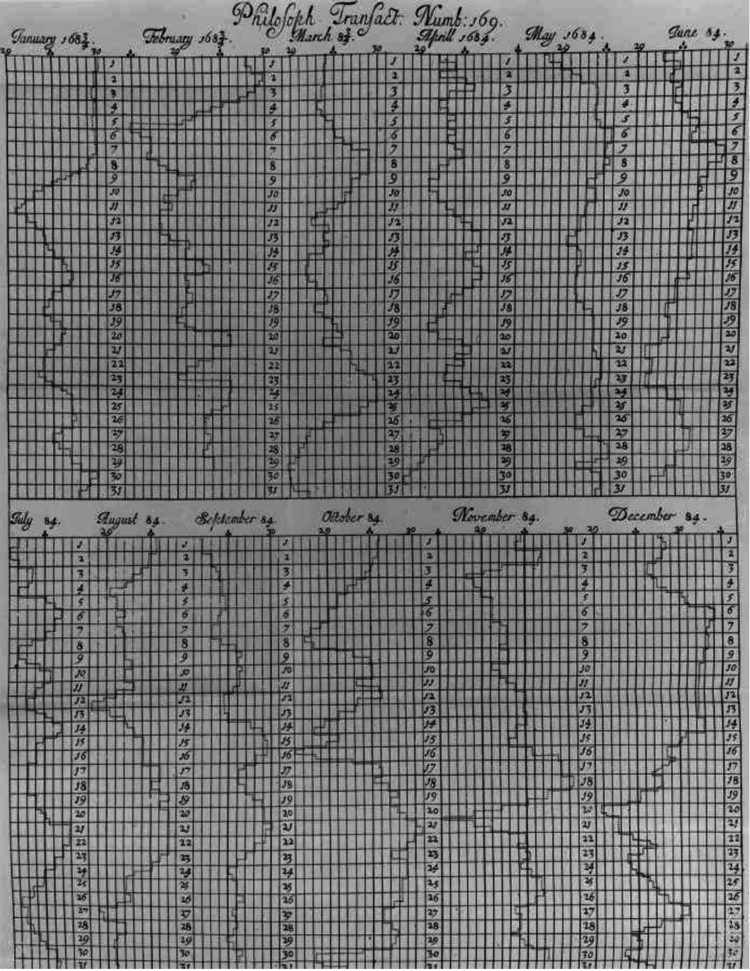

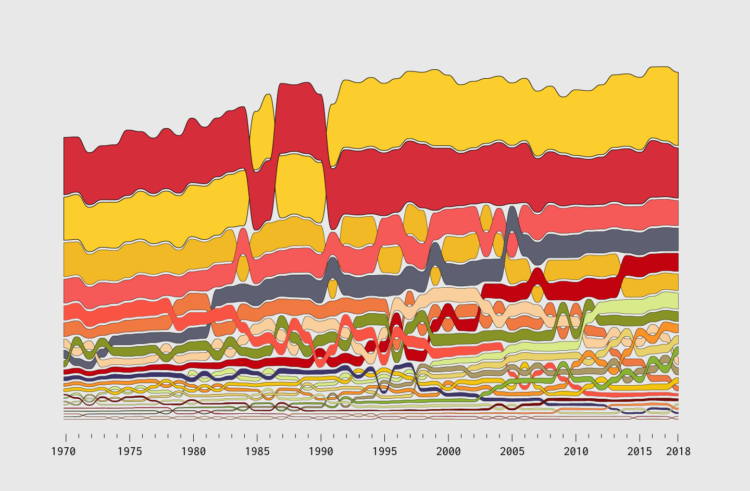

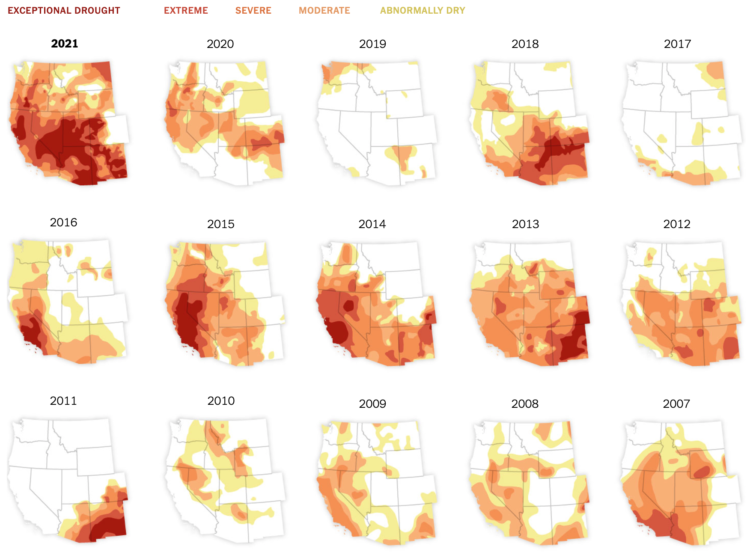

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)