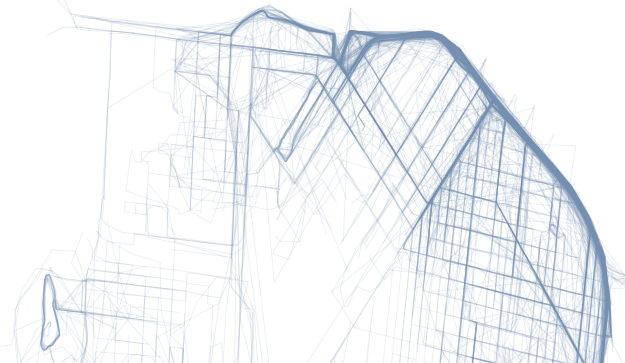

Kirk Goldsberry talks the rise of analytics usage in the NBA. With cameras above every court recording player movements, there’s a higher granularity analysis that is now possible, beyond the box score. One of the key metrics is expected possession value, or EPV, which estimates the number of points a possession is worth, given where everyone is on the court and where the ball is.

But the clearest application of EPV is quantifying a player’s overall offensive value, taking into account every single action he has performed with the ball over the course of a game, a road trip, or even a season. We can use EPV to collapse thousands of actions into a single value and estimate a player’s true value by asking how many points he adds compared with a hypothetical replacement player, artificially inserted into the exact same basketball situations. This value might be called “EPV-added” or “points added.”

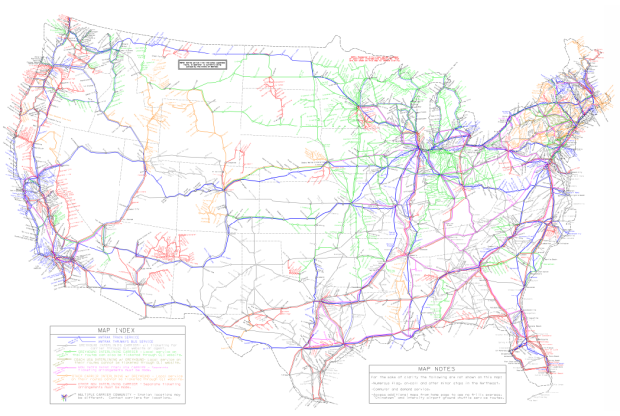

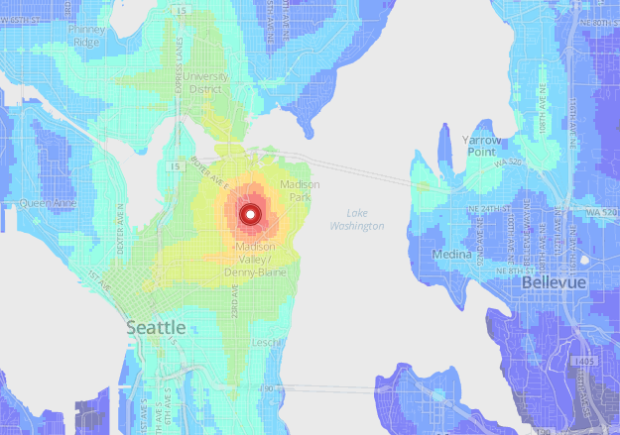

As a basketball fan, I hope this makes the game more fun and interesting to watch, and as a statistician, I hope this work can be applied to other facets of life like traffic or local movements. If just the latter, that’d be fine too.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)