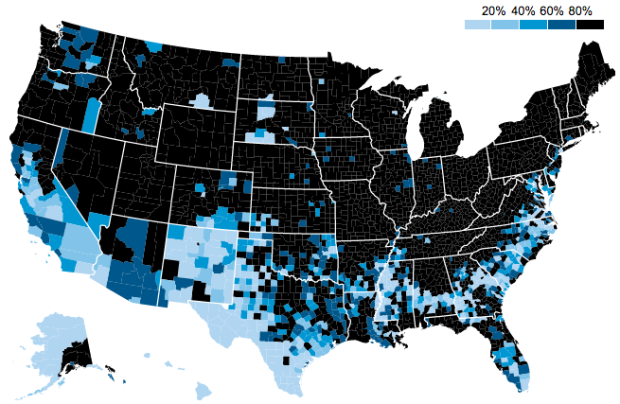

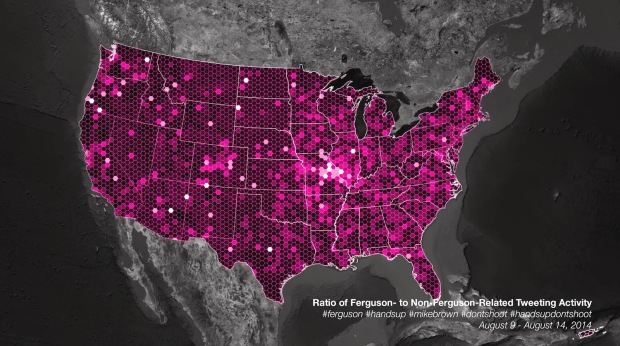

The map above by MetroTrends shows the percent of white kids who attended majority-white schools during the 2011-12 school year. Schools are still segregated in many areas of the country.

From Reed Jordan for MetroTrends:

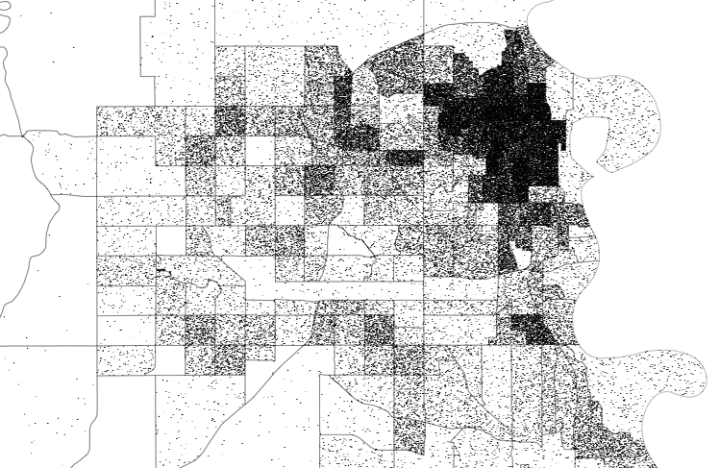

The separation of races is most clearly seen in large metropolitan counties that hold the bulk of a state’s population and most of its students of color. For example, in Chicago (Cook County), the overall student population is about 25 percent white, 31 percent black, and 37 percent Latino, but 96 percent of black students attend majority non-white schools and 67 percent of white students attend majority white schools. In other words, white students tend to attend schools with other white students and black and Latino students attend schools with other students of color.

Estimates are from the National Center for Education Statistics. [via @datatelling]

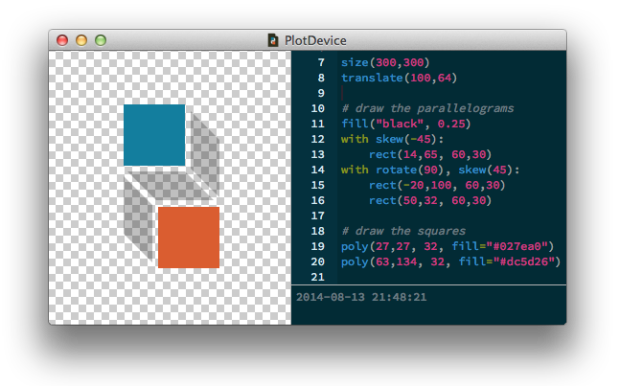

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)