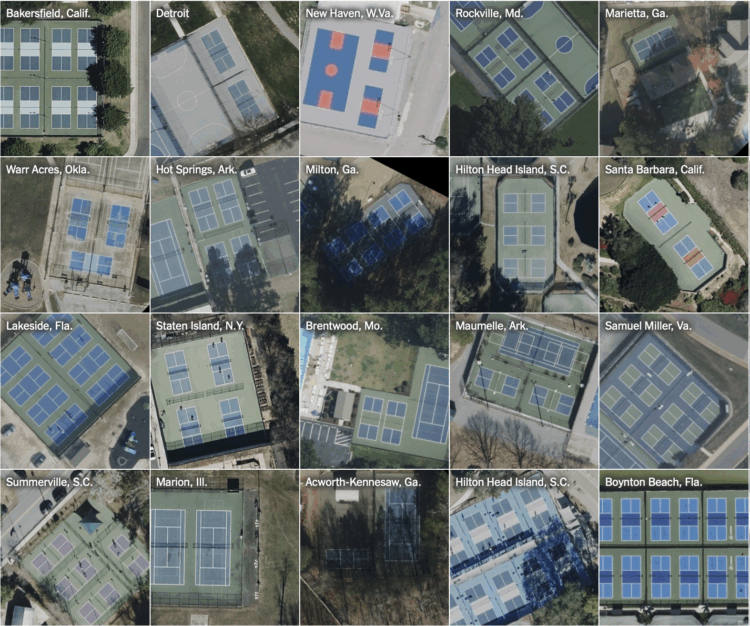

For NYT’s the Upshot, Ethan Singer found the birth of pickleball courts in aerial photographs.

By analyzing nearly 100,000 aerial photographs, we were able to identify more than 26,000 outdoor pickleball courts made in the last seven years — a majority of them at the expense of once-exclusive tennis spaces and created since the onset of the pandemic in 2020. In total, we found more than 8,000 tennis courts that had been transformed for pickleball.

Singer used computer vision to get precise coordinates of each court. Then he compared that data against old photographs to find tennis courts taken over by pickleball.

The sliding effect for before and after photographs works well here, given the contrast between a lone tennis court and a tennis court with four pickleball boundaries drawn on top.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)