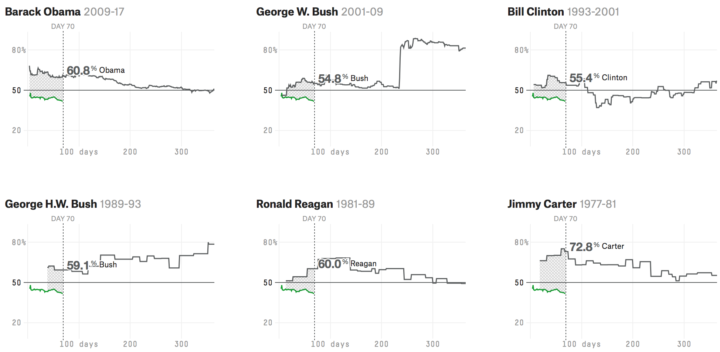

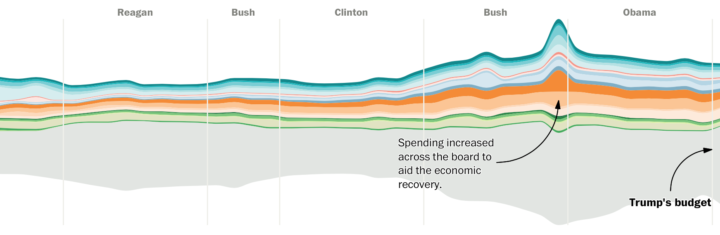

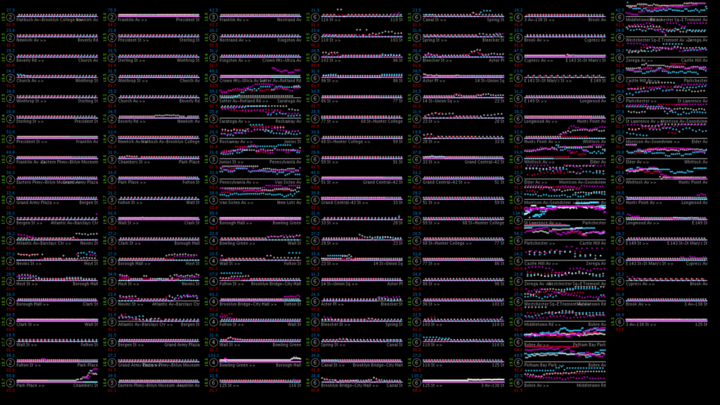

Using multiple polls as their source data, FiveThirtyEight is tracking approval and disapproval ratings for Donald Trump. The page leads with overall estimates with a couple of bands of uncertainty for projections into the next few months. I still wonder what proportion of readers understand the ranges, but I’m glad they’re there.

Scroll down the page to see how Trump’s ratings compare to past presidents. You can switch between approval, disapproval, and net approval, along with options to change the time span — which is nice for a page that updates for the next four years.

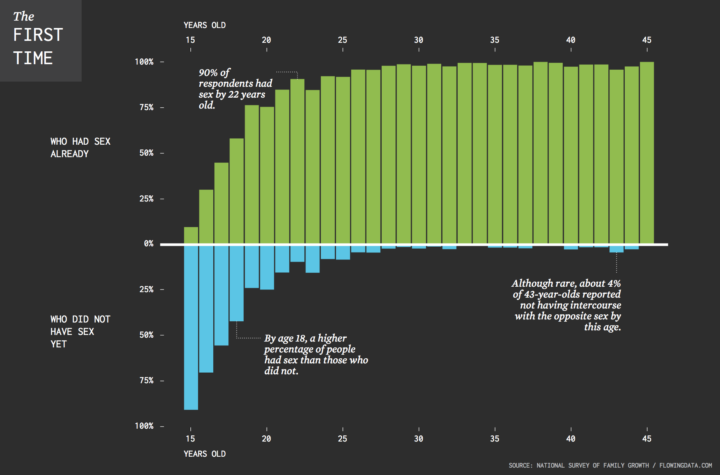

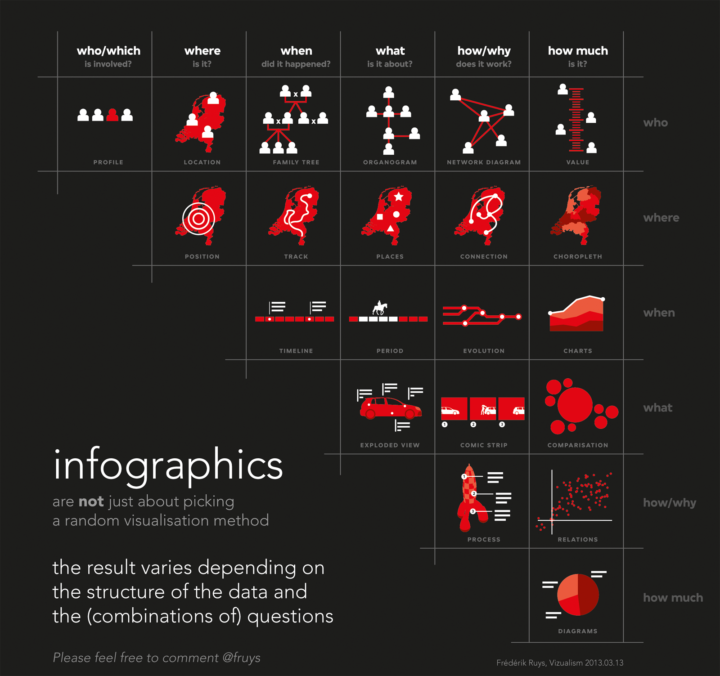

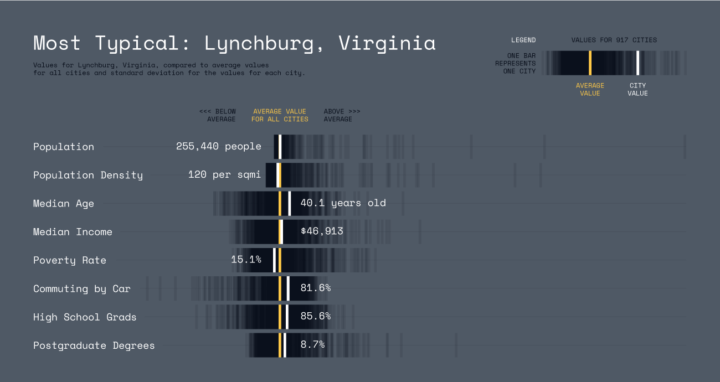

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)