File another one under the sounds-good-on-paper-but-really-challenging-in-practice. Kashmir Hill, for The New York Times, describes the challenges of new laws that allow users to request the data that companies collect on them:

Since then, two groups of researchers have demonstrated that it’s possible to fool the systems created to comply with G.D.P.R. to get someone else’s personal information.

One of the researchers, James Pavur, 24, a doctoral student at Oxford University, filed data requests on behalf of his research partner and wife, Casey Knerr, at 150 companies using information that was easily found for her online, such as her mailing address, email address and phone number. To make the requests, he created an email address that was a variation on Ms. Knerr’s name. A quarter of the companies sent him her file.

“I got her Social Security number, high school grades, a good chunk of information about her credit card,” Mr. Pavur said. “A threat intelligence company sent me all her user names and passwords that had been leaked.”

Yay.

I’m not saying these new laws are bad, but maybe get yourself a good password manager and change all those duplicate passwords.

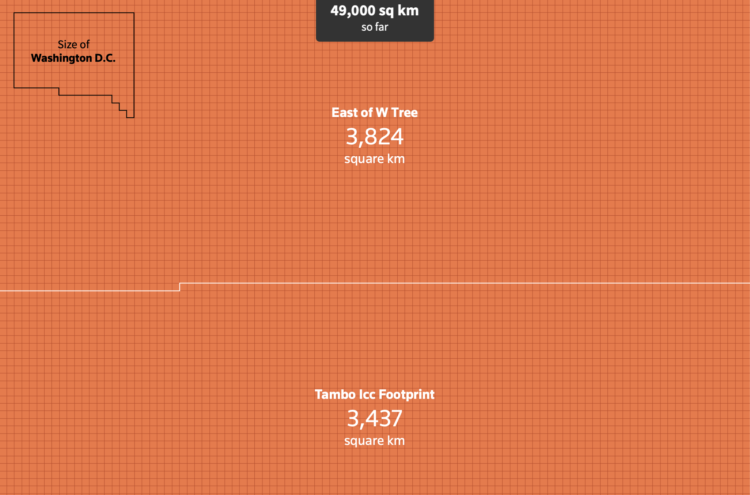

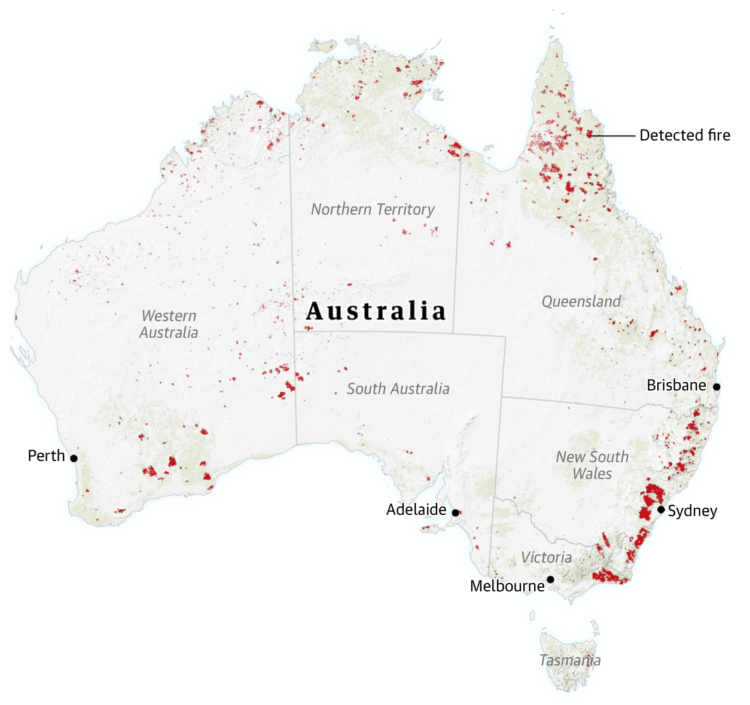

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)