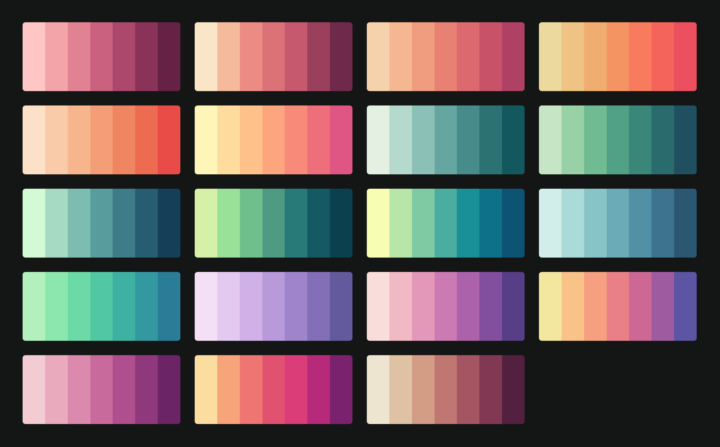

Picking colors is one my favorite things to do with visualization when I’m not in a rush for time. But when I can spare the minutes to pick and choose, it’s useful to have a quick reference. ColorBrewer is the go-to, but CARTOColors is a simpler take. It just shows you a bunch of schemes at once for sequential, diverging, and qualitative data. [via @maartenzam]

-

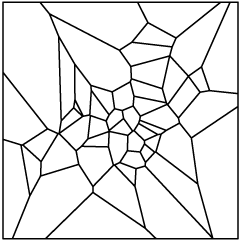

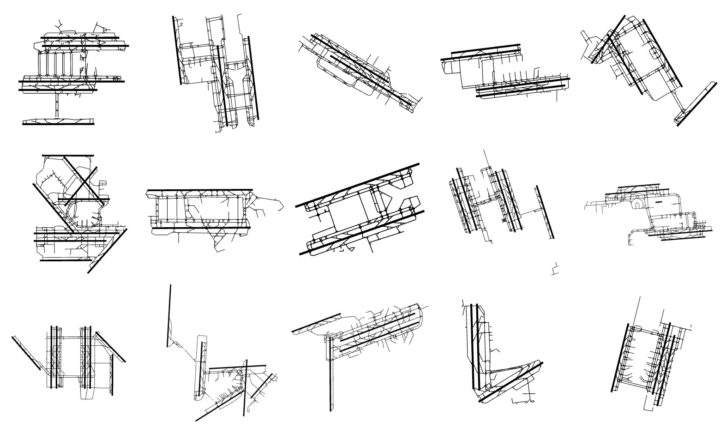

Cartographer Geraldine Sarmiento from Mapzen explores the drawing forms in cartography, such as lines, bridges, and buildings.

What is the visual language of cartography? Let’s explore this question through the medium of drawing. After all, it is this abstract representation of place onto a surface of fewer dimensions that the act of cartography entails.

Be sure to check out the Morphology tool to poke at the forms yourself.

-

Sleep. Work. Play. The times and everything in between change depending on who you talk to.

-

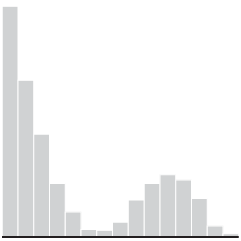

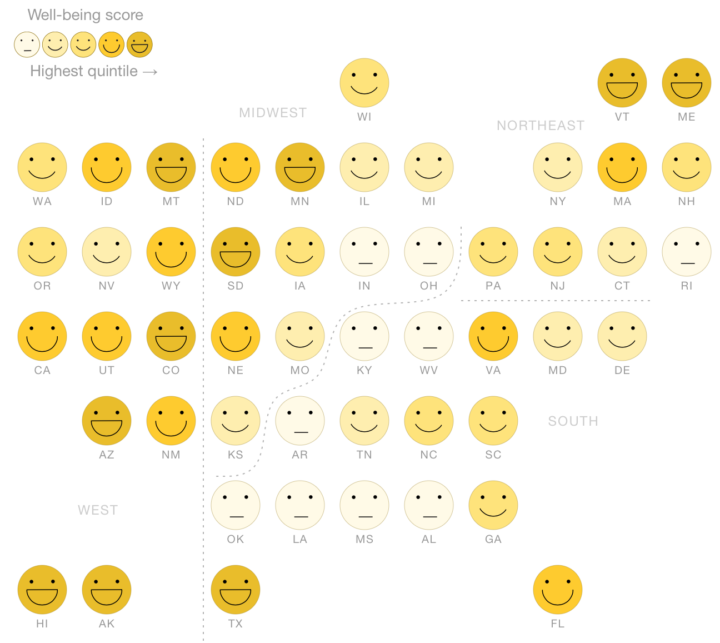

Gallup surveyed Americans about their well-being across various factors. National Geographic gets into some of the geographic breakdowns.

While Gallup’s survey doesn’t attempt to explain why individuals feel the way they do, it does expose some commonalities among the lives of Americans. Respondents from the lowest ranked states were more likely to report worse physical and financial health: They were more likely to smoke, be obese, and have little interest in life. They also reported not having enough money to buy food or healthcare.

You can grab the data from the Gallup site here.

-

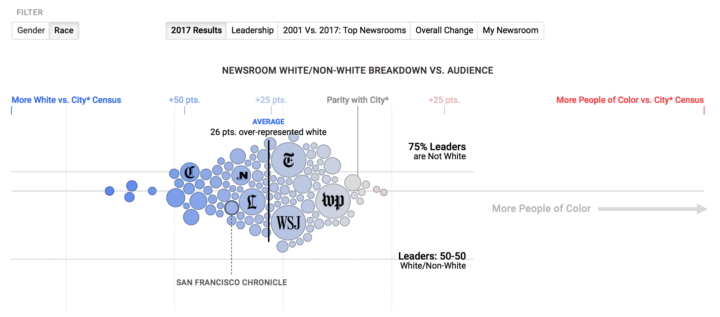

If a news organization wants to talk about the world in a fair way, it needs points of view from a group of people who are representative of said world. Otherwise, bias comes to play no matter how hard you try. Google Trends looks at the how different groups are represented in major news organizations across the country.

-

I’m surprised I’m just now hearing about Gyroscope. It’s an app that automatically tracks your health data and then generates reports, both digitally and in print format. An “OS for the human body” it says.

-

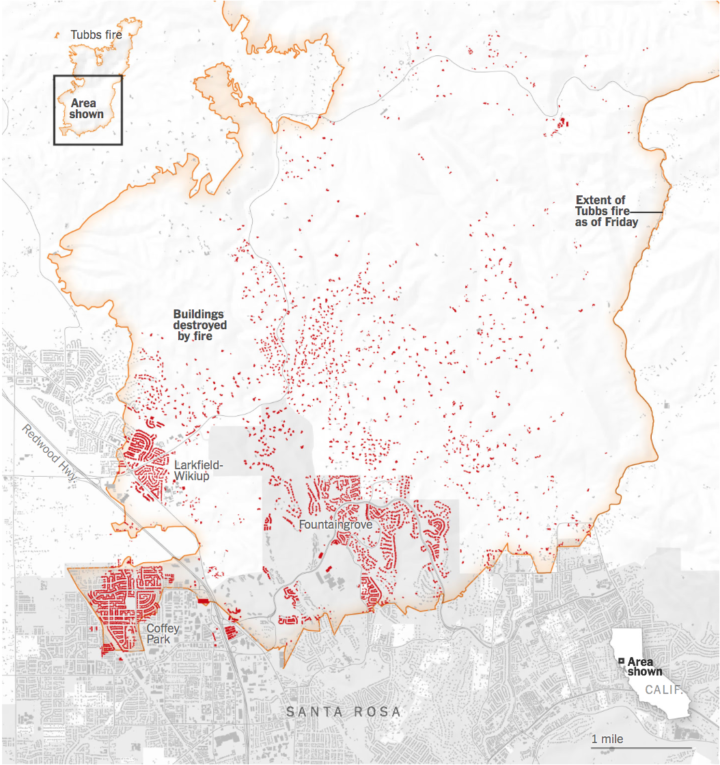

Using both satellite images and ground surveys, The New York Times maps the damage due to the fires in Santa Rosa. Crazy. I live a couple of hours away from the area and I still could smell the smoke.

See also Nicolette Hayes’ more personal map.

-

George Mauer highlights how a hacker might access other people’s data by putting an equal sign in a CSV file, so that an import to Microsoft or Google Sheets runs a value as a formula, even if it’s quoted as a string.

The attacker starts the cell with their trusty = symbol prefix and then points IMPORTXML to a server they control, appending as a querystring of spreadsheet data. Now they can open up their server log and bam! Data that isn’t theirs. Try it yourself with a Requestb.in.

The ultra sinister thing here? No warnings, no popups, no reason to think that anything is amiss. The attacker just enters a similarly formatted time/issue/whatever entry, eventually an administrator attempts to view a CSV export and all that limited-access data is immediately, and queitly sent away.

Oh goody.

-

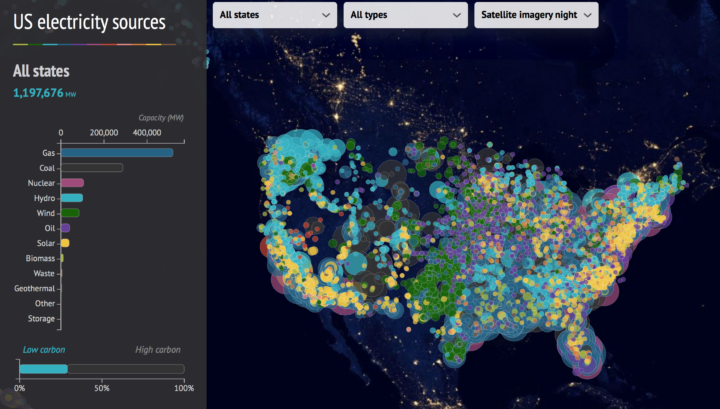

This interactive map from CarbonBrief shows how America generates electricity. Each circle represents a power source, color represents type, and size represents output.

See also a more edited version from The Washington Post a couple of years back.

-

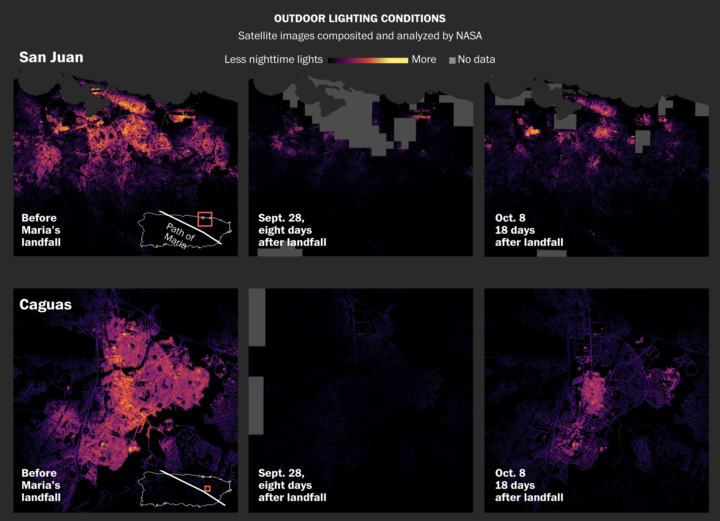

Three weeks in, much of Puerto Rico is still without power. Denise Lu and Chris Alcantara for The Washington Post map the lights at night, based on satellite composite data from NASA.

With more than 80 percent of the island’s 3.4 million people still without power, residents have relied on portable generators as workers across the island try to repair the damaged electrical grid.

In the days after Maria, many residents struggled to access gasoline, food, water, money and a cellphone signal to contact family members.

-

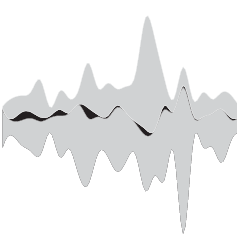

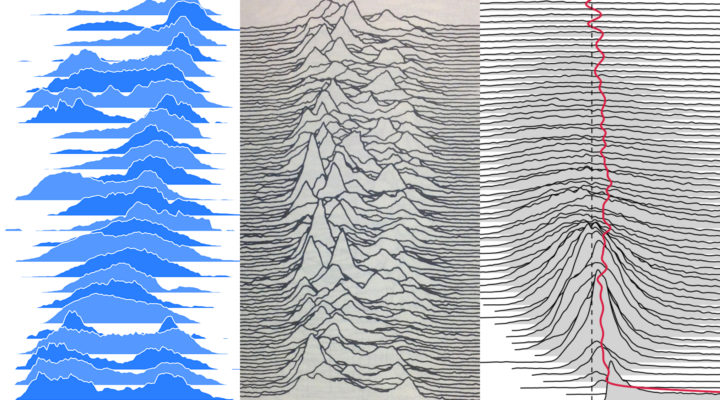

Frequency trails, or currently better known as joyplots, is a visualization method to show multiple distributions at once. Taken individually, each distribution is shown as a density curve, and they overlap each other for a three-dimensional effect. Luis Carli provides an interactive explainer for the method.

I haven’t been able to put my finger on it, but I think there’s something about the overlapping that sort of serves as a visual signal to compare. It seems more direct than small multiples or non-overlapping densities? Or, are people just appreciating the novelty for now?

-

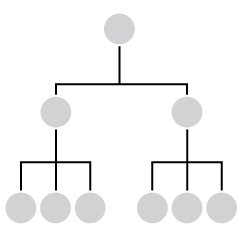

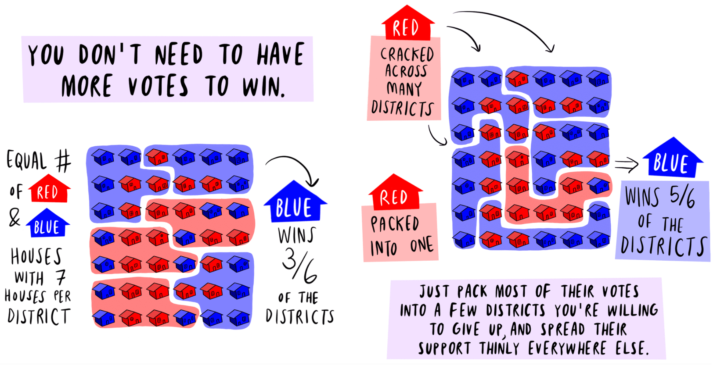

Gerrymandering doesn’t sound like an especially sexy topic, but it’s an important one to pay attention to. District lines are drawn in roundabout ways sometimes to favor a party. This used to be a manual process, but math and computing has made it much easier to sway these days. Olivia Walch explains how math can be used to swing line drawing to a more equal process.

See also the gerrymandering game for another point of view.

-

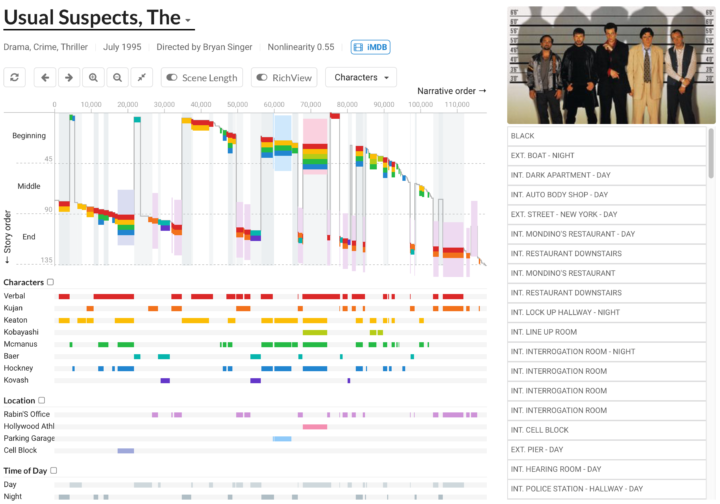

Many stories don’t follow a linear format. There are flashbacks, or multiple timelines run simultaneously. Story Curves is a research project that tries to visualize the back and forth.

Read More -

Unfortunately, while of varying magnitude, mass shootings are somewhat regular in the United States.

-

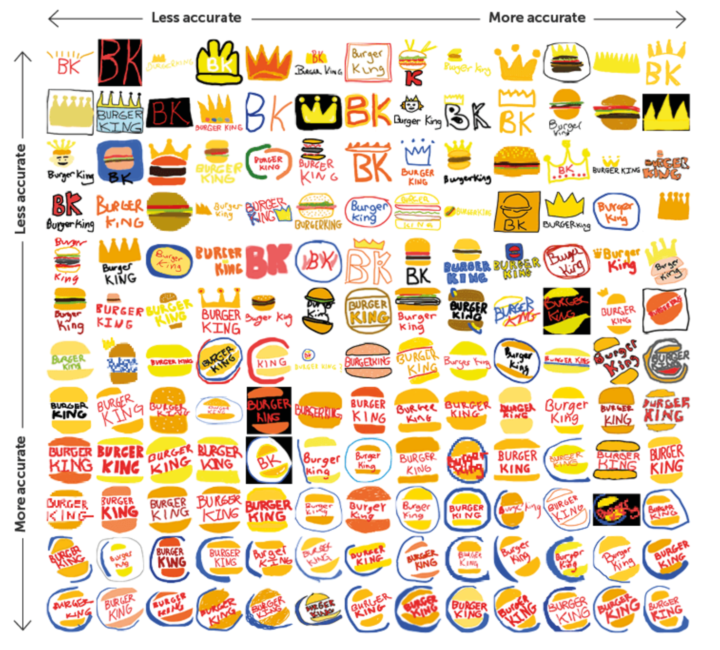

Signs asked 150 people to draw famous logos — Apple, Starbucks, Burger King, etc. — from memory, and they compiled the results. It’s a relatively small sample size and drawing accuracy was judged subjectively, so I’d put this more in the fun category than an actual study, but I like the spectrums.

-

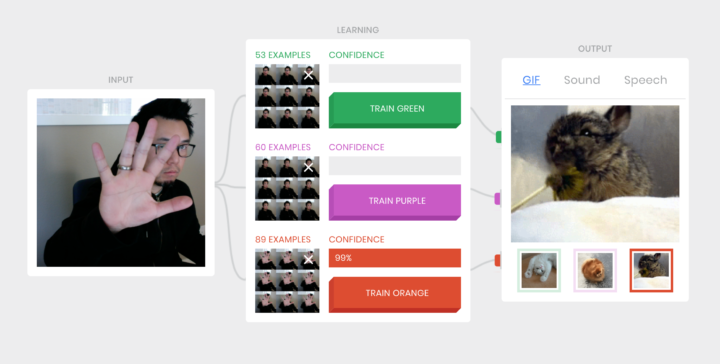

The Teachable Machine from Støj, Use All Five, and Google is a fun experiment that lets you “teach” your computer. Your webcam is used as an input device, and using deeplearn.js, you can make three classifications that change the output. Use different hand gestures, faces, or movements to signal differences, and you can see probabilities change in real-time.

It’s hard to believe this stuff runs so smoothly in the browser now. I remember learning this back in college. The training and usage in some heavy software package was laborious.

-

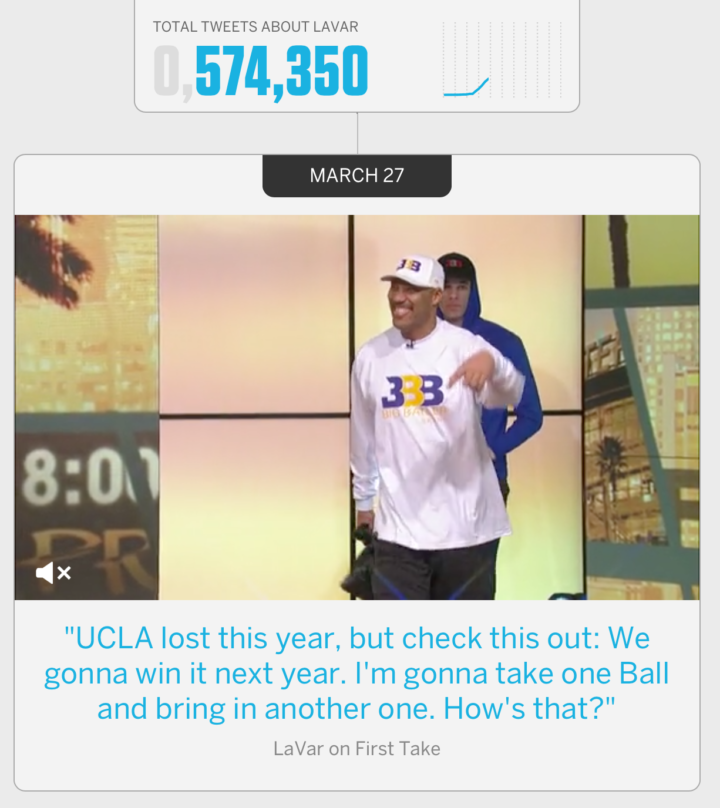

I didn’t know who LaVar Ball was, and suddenly, it was non-stop sports news about the Ball family. If you’re unfamiliar, LaVar Ball is the father of a now professional basketball player. Before his son was drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers, Ball garnered attention for saying trollish things like he could’ve beat Michael Jordan one-on-one in his heyday.

Anthony Olivieri for ESPN outlines the rise of the loud talker using a simple tweet count and line chart as the backdrop.

-

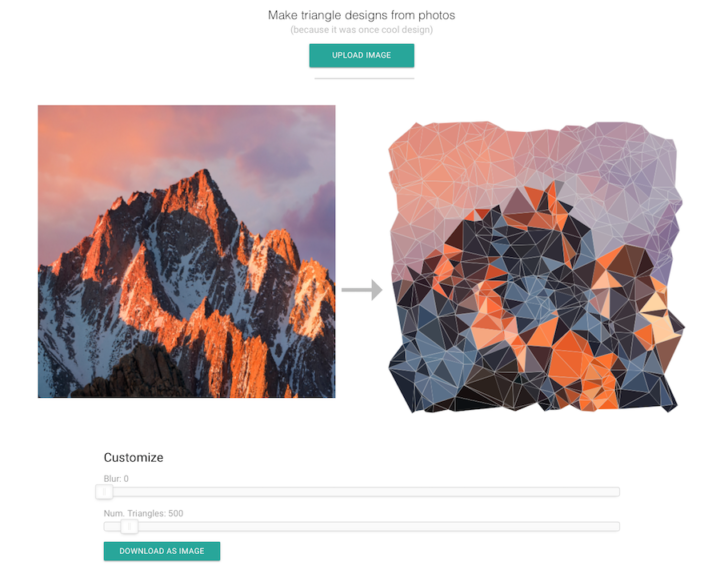

Triangulate, a fun tool made by Michael Freeman, lets you upload a picture and it randomly assigns points to output something that looks pixelated but with triangles. Give it a try.

-

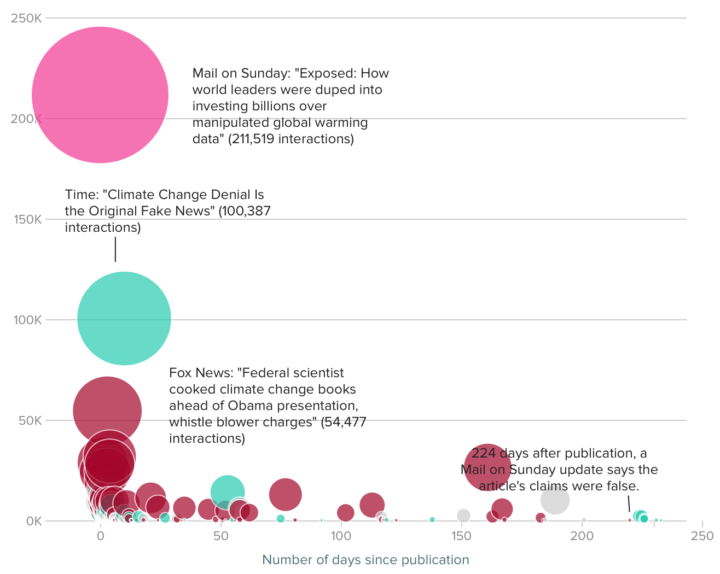

BuzzFeed describes how an article on Daily Mail — that falsely reported claims and data about climate change — went viral. Seven months since publishing, the British site finally admitted they were wrong, long after they got all their clickbait traffic I am sure.

This doesn’t surprise me, as I had poor experiences with Daily Mail, but it does surprise me that such a large site is allowed to keep chugging along as if they’ve done nothing wrong.

-

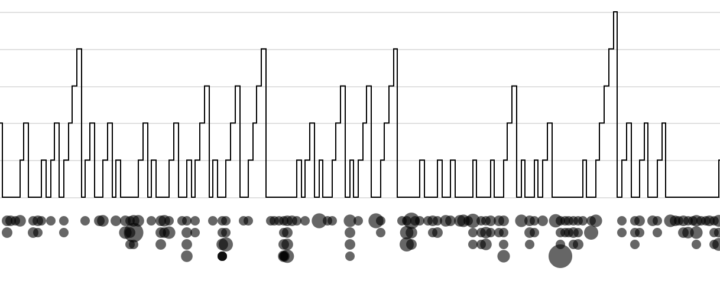

How I Made That: Interactive Beeswarm Chart to Compare Distributions

The histogram is my favorite chart type, but it’s unintuitive for many. So I’ve been using the less accurate but less abstract beeswarm.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)