As data grows cheaper and more easily accessible, the people who analyze it aren’t always statisticians. They’re likely to not even have had any statistical training. Biostatistics professor Jeff Leek says we need to adapt to this broader audience.

What does this mean for statistics as a discipline? Well it is great news in that we have a lot more people to train. It also really drives home the importance of statistical literacy. But it also means we need to adapt our thinking about what it means to teach and perform statistics. We need to focus increasingly on interpretation and critique and away from formulas and memorization (think English composition versus grammar). We also need to realize that the most impactful statistical methods will not be used by statisticians, which means we need more fool proofing, more time automating, and more time creating software. The potential payout is huge for realizing that the tide has turned and most people who analyze data aren’t statisticians.

Yep.

Those who disagree tend to worry what might happen — what kind of data-based decisions will be made — by non-statisticians, and that should definitely be a priority as we move forward. Non-statisticians often make incorrect assumptions about the data, forget about uncertainty, and don’t know much about collection methodologies.

However, as a statistician (or someone who knows statistics), you can shoo everyone else away from the data and gripe when they come back, or you can help them get things right.

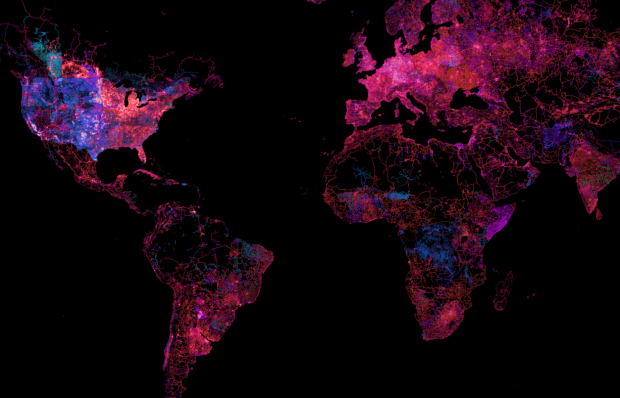

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)