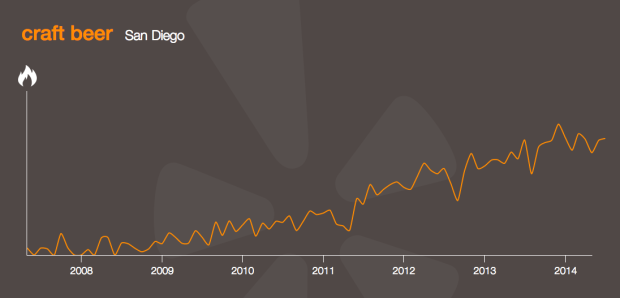

Yelp released an amusing tool that lets you see how the use of word in reviews has changed over the site’s decade of existence.

From food trends to popular slang to short-lived beauty fads (Brazilian blowout anyone?), Yelp Trends searches through words used in Yelp reviews to show you what’s hot and reveals the trend-setting cities that kicked it all off. Our massive wealth of data and the high quality reviews contributed by the Yelp community are what allow us to surface consumer trends and behavior based on ten years of experiences shared by locals around the world.

Just type in keywords, select your city, business category, and click the search button to see the changes. For the less used words, the data looks mostly like noise, but there are also some clear trends like in craft beer and chicken and waffles.

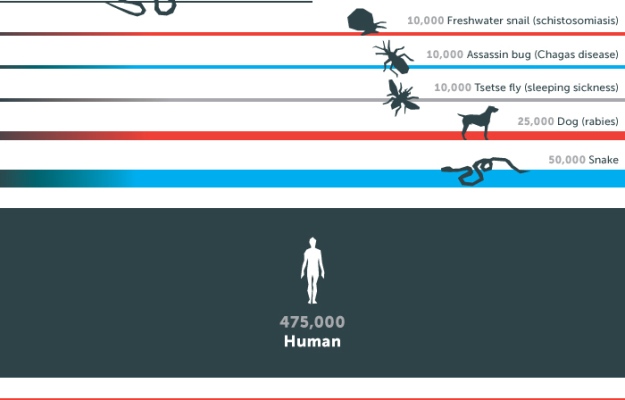

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)