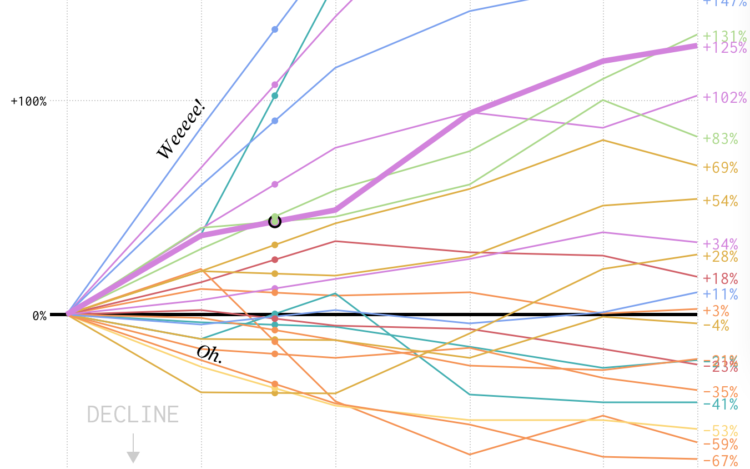

Datawrapper, a focused web tool that makes online charts easier to put together and share, changed their pricing structure. There used to be a couple of paid tiers for individuals and small teams, but now you get more for free. And even though it’s free:

- We won’t sell your data. Some companies make the user into the product, but this is not our business model. All data you upload to Datawrapper is treated as confidential and only belongs to your account.

- We won’t track your readers. Your embedded charts will not contain any code that tracks you or your readers. We’ve never done that, and will continue to not do that, regardless of your plan.

- Your charts are private. You decide when it’s time to share your charts with the world. Until you hit “Publish”, your charts are visible only to you and your team.

- Published charts will stay online indefinitely. We will never delete or disable any of your Datawrapper visualizations that you embedded somewhere. We stand by our pledge to keep all our users’ charts online.

They continue to impress.

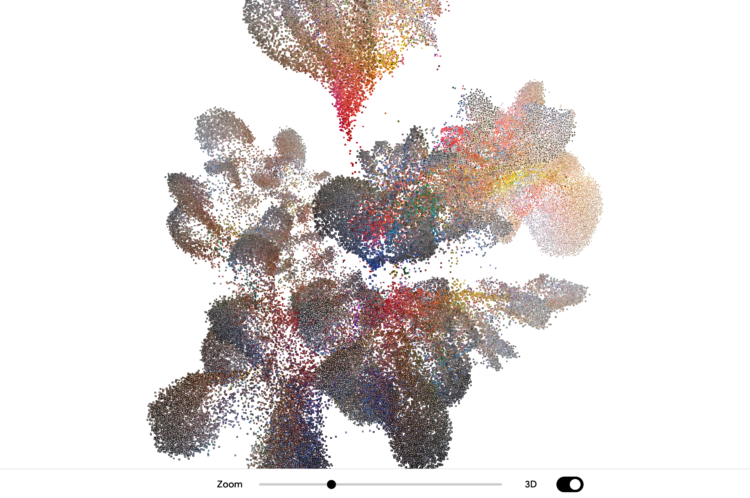

It wasn’t that long ago when online charting tools felt buggy and overly limited. But Datawrapper is laying some strong groundwork (and Flourish continues to build up their offerings). Instead of a one-size-fits-all, we’re seeing an application focus, which allows for more specific tools.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)