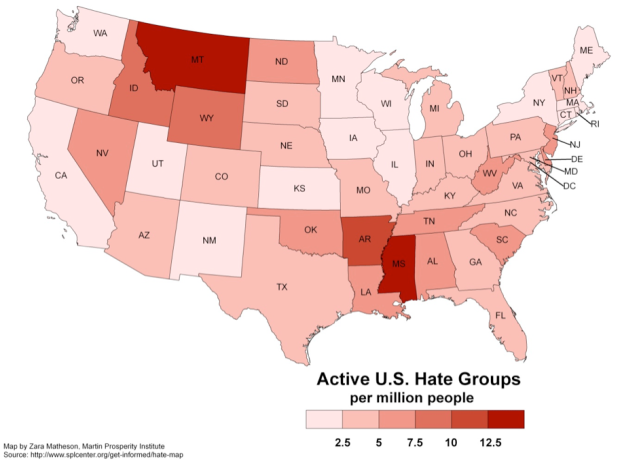

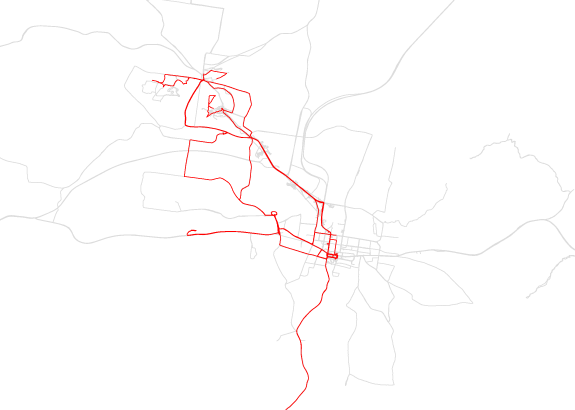

Richard Florida for The Atlantic takes a closer look at hate groups in the United States:

Since 2000, the number of organized hate groups — from white nationalists, neo-Nazis and racist skinheads to border vigilantes and black separatist organizations — has climbed by more than 50 percent, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). Their rise has been fueled by growing anxiety over jobs, immigration, racial and ethnic diversity, the election of Barack Obama as America’s first black president, and the lingering economic crisis. Most of them merely espouse violent theories; some of them are stock-piling weapons and actively planning attacks.

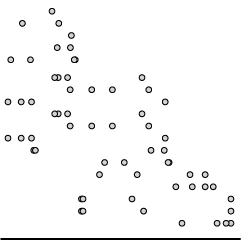

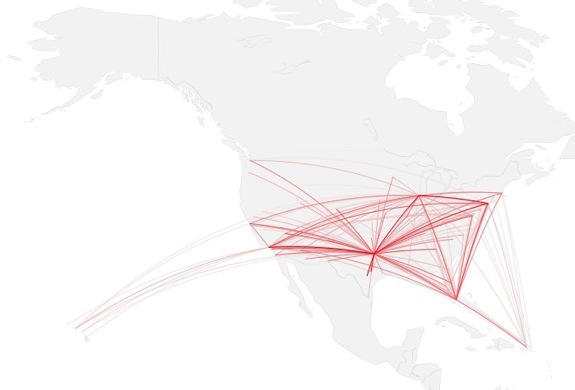

The map provides a basic state-by-state view of hate groups per capita. Montana and Mississippi have the highest rates. Straightforward stuff. The interesting part, however, is how the rate correlates to other factors, such as support for John McCain. The greater the support for McCain, the more hate groups per capita a state tends to have.

Read More

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)