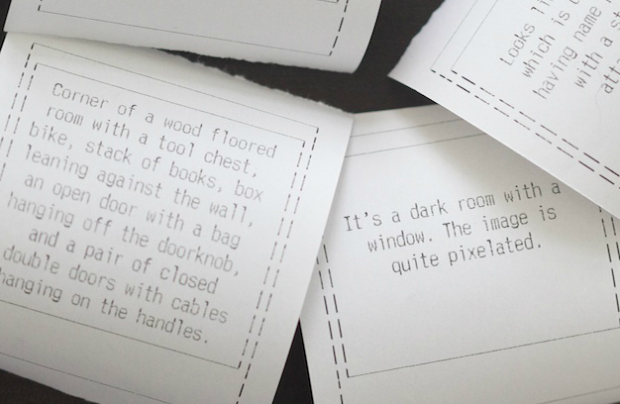

Garbage in, garbage out the old adage goes. Nigel Hawkes, Director of Straight Statistics, describes a sort of statistical whistleblowing letter to the British Medical Journal.

A team from Imperial College found that in 2009-10, nearly 20,000 adults were coded as having attended paediatric outpatient services, and 3,000 patients under 19 were apparently treated in geriatric clinics. Even more striking, between 15,000 and 20,000 men have been admitted to obstetric wards each year since 2003, and almost 10,000 to gynaecology wards.

It’s hard to put your faith in analysis, visualization, policy, and anything else that comes out of data with reports like these. With human error being a known issue, we have to find better ways of inputting and double-checking data. Unfortunate mistakes at the outset only lead to bigger problems down the line.

Maybe I’m just stuck in my ways, but I’m having trouble getting on board with these tools. Easel.ly, for example, provides themes, such as the one on the right. There’s a guy in the middle with graphs around him and pointers coming out of his body. You get to edit however you want.

Maybe I’m just stuck in my ways, but I’m having trouble getting on board with these tools. Easel.ly, for example, provides themes, such as the one on the right. There’s a guy in the middle with graphs around him and pointers coming out of his body. You get to edit however you want.  Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)