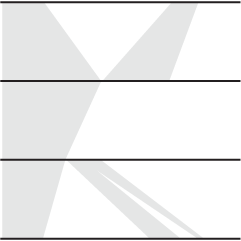

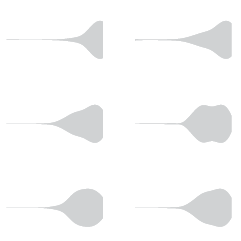

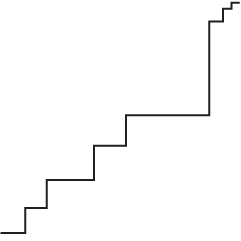

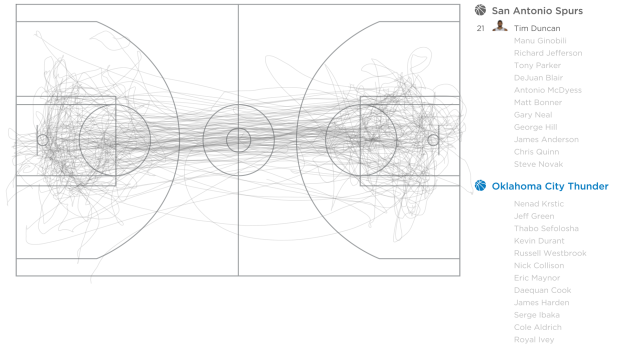

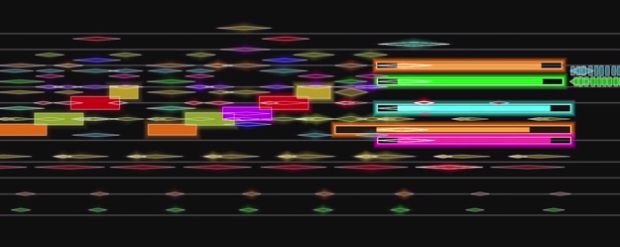

The NBA has been kind of gaga over data the past few years, and they recently announced that all 30 teams would have player tracking installed so they can see where they go at night after games. Wait, no. I mean so that there is data on where each player is on the court at any given time. Fathom Information Design played with some of this data for an Oklahoma City versus San Antonio game, with some sketches.

Above are the movements of power forward Tim Duncan, who sticks around the middle of the court throughout a game. A guard on the other hand, runs around the court more. This is obvious if you’ve watched him play, but sketches like this coupled with spatiotemporal analysis could be interesting.

Also, I get the sense that there’s more people who want to know about this data than there are who know how to, so if you’re a statistician on the job hunt, there’s that.

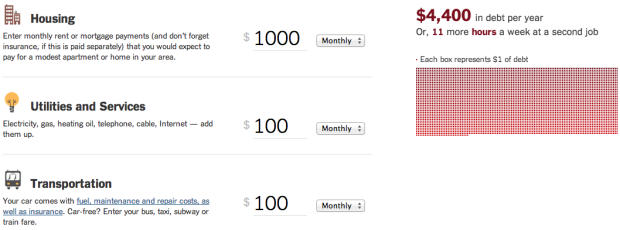

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)