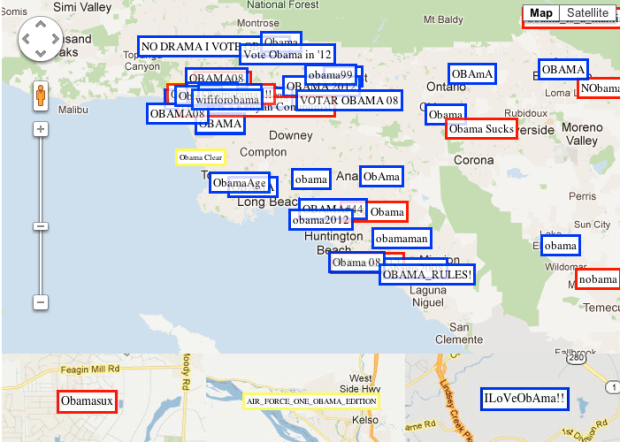

Wireless network SSIDs in residential areas are typically left on default router names like Belkin or LinkSys, but some people use them as a subtle way to broadcast a message. Sometimes it’s simple like “DontStealMyInternet” or “Big Bob’s playhouse.” Others use their SSIDs to make a political statement. With that in mind, James Robinson, a developer for OpenSignalMaps, wondered if political allegiance could be inferred from assigning sentiment to SSIDs.

According to this eccentric measure of sentiment Obama is much more popular outside of the US than within. Why is this? It may be that Obama is genuinely more popular in the rest of the world but maybe it is because outside of the US people are less likely to express negative sentiments towards politicians in this manner. We can’t answer this definitively but looking at Argentina, at least, does suggest this is the case.

I’m surprised it was so evenly split in the US between negative and positive since in a way it’s like putting a sign up on your lawn. Usually you see signs in support of a candidate rather than one that says an opposing candidate sucks.

Anonymity probably plays the main role in this case. You can’t put up a mean sign in front of your house and pretend it’s not yours, but you can make an insulting SSID, and no one would be the wiser.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)