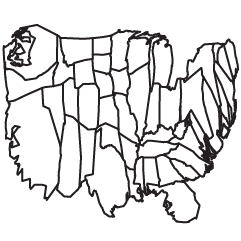

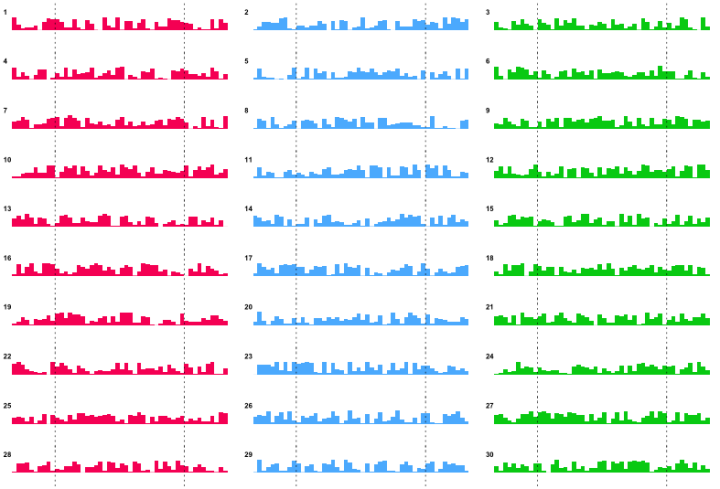

Researchers Pengyu Zhua and Yaoqi Zhang noted in their 2008 paper that “the demand for urban forests is elastic with respect to price and highly responsive to changes in income.” Poor neighborhoods tend to have fewer trees and the rate of forestry growth is slower than that of richer neighborhoods.

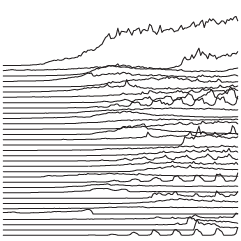

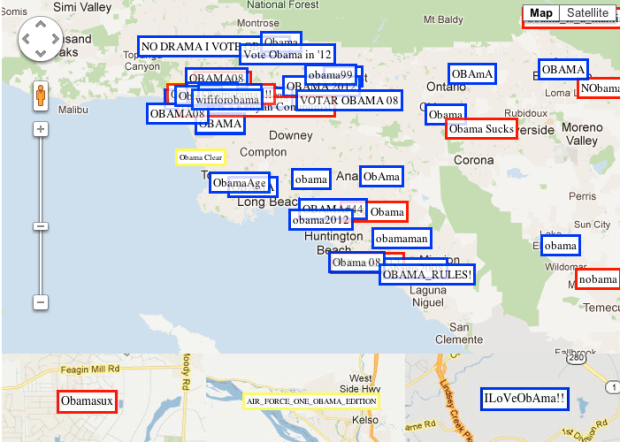

Tim De Chant of Per Square Mile wondered if this difference could be seen through satellite images in Google Earth. It turns out that you can see the distinct difference in a lot of places. Above, for example, shows two areas in Rio de Janeiro: Rocinha on the left and Zona Sul on the right. Notice the tree-lined streets versus the not so green.

De Chant notes:

It’s easy to see trees as a luxury when a city can barely keep its roads and sewers in working order, but that glosses over the many benefits urban trees provide. They shade houses in the summer, reducing cooling bills. They scrub the air of pollution, especially of the particulate variety, which in many poor neighborhoods is responsible for increased asthma rates and other health problems. They also reduce stress, which has its own health benefits. Large, established trees can even fight crime.

Okay, I don’t now about that last part about fighting crime. Without seeing the data, I think that sounds like a correlation more than anything else, but still. Trees. Good.

[via Boing Boing]

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)