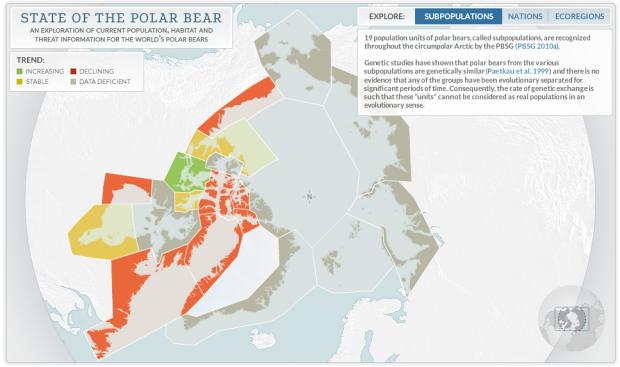

There are an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 polar bears in the world, and the population is expected to decline by 30 percent over the next three generations. Periscopic, in collaboration with the Polar Bear Specialist Group, highlighted the changing populations in this interactive.

The data can be viewed by subpopulation, by nation, and by ecoregions. In the first two views, you can click on geographic regions to see more details about the area, which includes a text overview and time series for more troubling numbers on polar bears killed by humans and pollution. Finally, when you click on a time series or the pollutant levels, you can see the data at a higher granularity.

So there are a few ways to examine the data and different angles to explore. You’ll want spend some time with this one.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)