-

Data is an abstraction of something that happened in the real world. How…

-

This video clearly describes the distribution of wealth in America using a set of transitioning charts. The graphics are good. The explanation is better.

-

-

-

-

Data visualization group Dataveyes looks closer at the Paris metro system from a time and crowd point of view.

This visualization offers to challenge the way we traditionally view our 2D metro maps. Métropolitain takes on an unexpected gamble: using cold, abstract figures to take the pulse of a hectic and feverish metropolis. The metro map is no longer arbitrarily dictated by the spatial distance between two points. By playing around with two extra variables — time and crowds — users can transform the map, view it in 3D and unveil the true reality behind their daily commute.

No doubt inspired by the Travel Time Tube Map of the London Underground by Tom Carden, Métropolitain lets you select a station and the lines morph to represent how long it takes to get to other stations. A layer underneath is a heatmap that shows annual incoming traffic per station.

Finally, you can switch between 2-D and 3-D. I’m not sure if the extra dimension adds much from an understanding point of view, but it is fun to play with. [via infosthetics]

-

Over the last 12 years, astronauts have taken a lot of pictures from the International Space Station. About 1.1 million of them. And they’re all archived on NASA’s servers. Nathan Bergey mapped them.

Most of the photos are taken of land. Coastlines, islands and cities seem to be popular targets. So much so that it’s possible to make out basic continents. This makes sense, photos of clouds over an otherwise blank ocean get old after a while. I’m sure every astronaut has taken at least one photograph of the town they grew up in.

Above is the use of small multiples to show pictures taken during separate missions.

-

Periscopic founders Kim Rees and Dino Citraro spoke with Co.Design on what makes good visualization.

“I don’t think the goal of vizualization should be that precog understanding, giving you something so quickly that you don’t have to think about it; I think the goal should be that you do have to think about it,” she says. “I want people to have a brain, to have a say. I think it’s becoming only more important as we tackle more nuanced information. I don’t want the computer or the creator to tell me what to believe. I want an opening to say, ‘let me look into that machine.'”

-

-

-

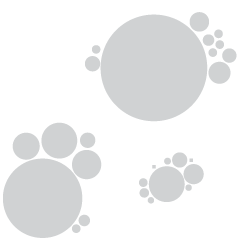

How much space is there per person in different countries? Andrew Bergmann for CNNMoney took a look.

Population density measures the amount of people in a given area, generally per square kilometer or mile. It’s difficult to get a clear image of what these vast spaces actually represent, so I thought that it would be interesting to flip the equation on its head and figure out how much space there is on average per person.

The interactive shows 20 countries and each is represented by a circle sized by average square feet per person. Of course, as with population density, this data is broad with land distribution and usage to consider, but it’s informative from a general viewpoint. Although the math might be slightly off in the square feet calculation. Or maybe that’s just rounding.

I’m surprised I haven’t seen something like this before. See population density from the more traditional point of view here, here, and here. Oh, and here. I think the last one is my favorite.

-

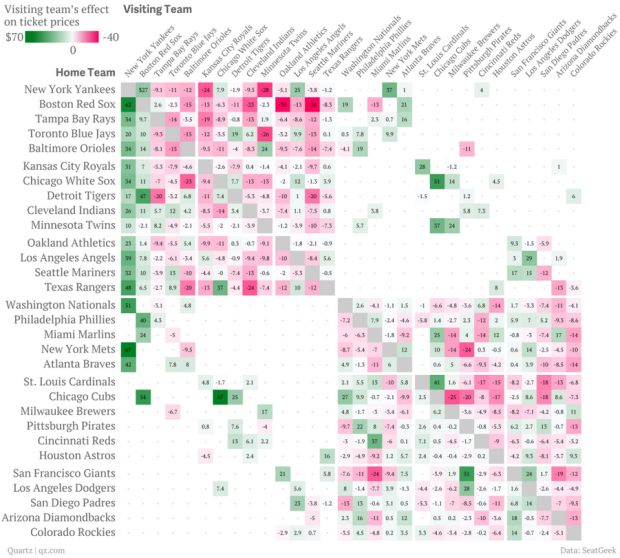

If you’ve ever looked at ticket prices for sporting events, you probably noticed the disparity in prices of when your team plays a popular team or a rival versus a less than stellar team. Last time I looked a ticket to watch the Golden State Warriors play the Lakers or Heat was twice as much as when they played the Kings. David Yanofsky for Quartz noted the same pricing strategy in baseball.

The heat map above shows the effect of visiting teams on ticket prices. As you’d expect (if you follow baseball even just a tiny bit), price goes up significantly when the New York Yankees come to town. In contrast, the price goes down when the Seattle Mariners show up.

There’s clearly a supply and demand thing going on here. Nobody wants to see bad teams play. But now it’s time to pull a Billy Beane. How little can you spend on a team and a stadium and still make a profit? [Thanks, David]

-

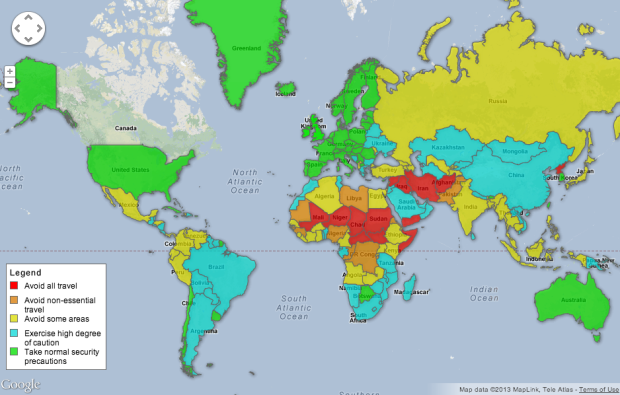

As summer rolls around here on this side of the planet, CBC News mapped countries to avoid in your travel plans, based on foreign travel advisories from the Canada Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

Naturally, Canada isn’t colored on the map because the map was made for Canadians, but I think it’s safe to assume that they’d be colored green too and most, if not all, of the advisories apply to those of us here in the United States. [Thanks, John]

-

-

I’m gonna be out of the country for a while. If all goes according to plan, you won’t notice I’m gone, but if it gets quiet all of a sudden you’ll know why. Comments will be off. I also won’t be very good with email during this time. Not that I was good with it to begin with.

gtg.ttyl

-

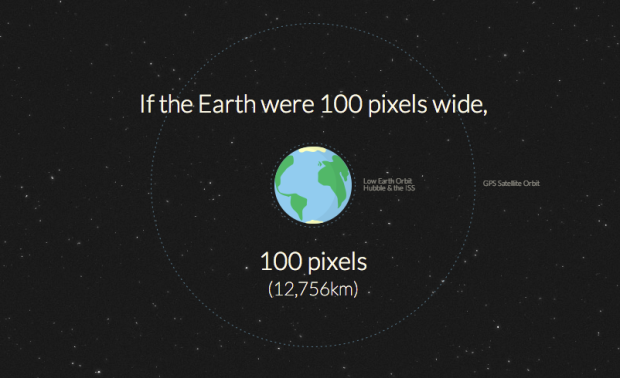

Long distances (and big numbers) can be difficult grasp. Designers Jesse Williams and David Paliwoda took a stab at it and made it easier to understand the distance from Mars. Simple and totally fun. I’m not sure how accurate the travel time and distance are, but I’m guessing it takes differing orbits into account.

-

There’s a strand of the data viz world that argues that everything could be a bar chart. That’s possibly true but also possibly a world without joy.

—Amanda Cox, 2013

There’s a great interview with Amanda Cox from The New York Times on visualization, some of the skills required, and where the field is headed. I like this tidbit on design, which is a contrast to the above:

Design and typography do matter. It’s about hierarchy of information and how people perceive information. Done properly, that clean up work really matters. On the other hand, it’s easy to believe that it matters more than it does. If you make a fantastically interesting chart and some poor design decisions, the data will still come through. If you make a bad chart with a beautiful design, what have you done, really?

Read the whole thing. Thank me later.

-

Melting snowpacks feed into streams and rivers and serve as a source of water for nearby communities. The Snow Water Equivalent Cabinet by artist Adrien Segal represents the amount of water in snowpack in Ebbetts Pass, California.

Each drawer is one year of data for a total of 31 years – 1980 – 2010. The size of the drawer is directly related to the amount of water stored in the snowpack for the given year. Some of the drawers are so shallow that they are barely functional. Wet years have larger drawers.

I understand the metaphor behind the limited functionality at low water points, but a totally functional version would be a sexy piece in a studio. Snow Water is currently on display at the Richmond Art Center as part of the Innovations in Contemporary Crafts exhibition until June 1. [Thanks, Michael]

-

Whoa, that was fast. Data Points is now available. Thanks to all of you for making this possible.

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)