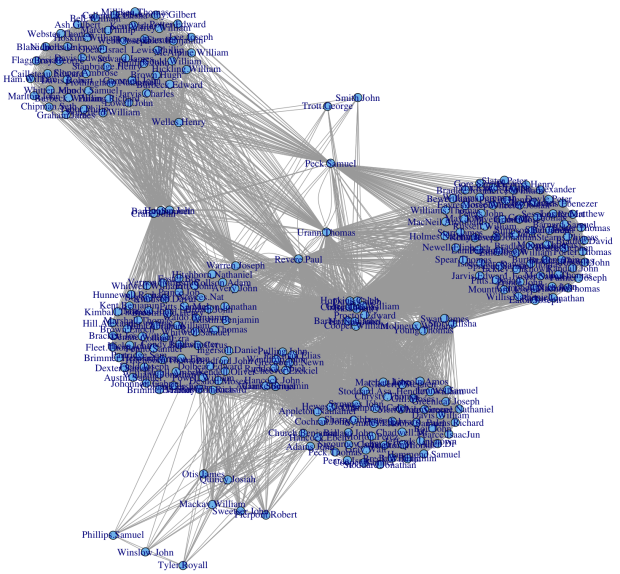

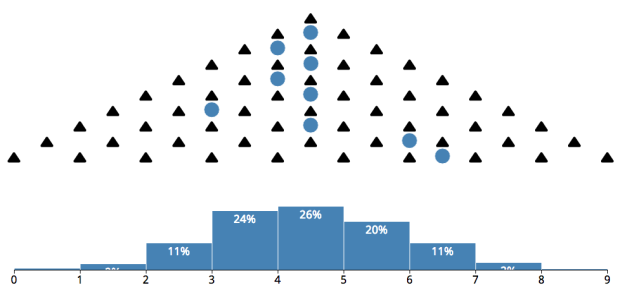

Curious about how people use “geek” and “nerd” to describe themselves and if there was any difference between the two terms, Burr Settles analyzed words used in tweets that contained the two. Settles used pointwise mutual information (PMI), which essentially provided a measure of the geekness or nerdiness of a term. The plot above shows the results.

In broad strokes, it seems to me that geeky words are more about stuff (e.g., “#stuff”), while nerdy words are more about ideas (e.g., “hypothesis”). Geeks are fans, and fans collect stuff; nerds are practitioners, and practitioners play with ideas. Of course, geeks can collect ideas and nerds play with stuff, too. Plus, they aren’t two distinct personalities as much as different aspects of personality. Generally, the data seem to affirm my thinking.

Or maybe pop culture (geek) versus education (nerd).

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)