Not many people understand the importance of data privacy. They don’t get out how little bits of information sent from your phone every now and then can show a lot about your day-to-day life.

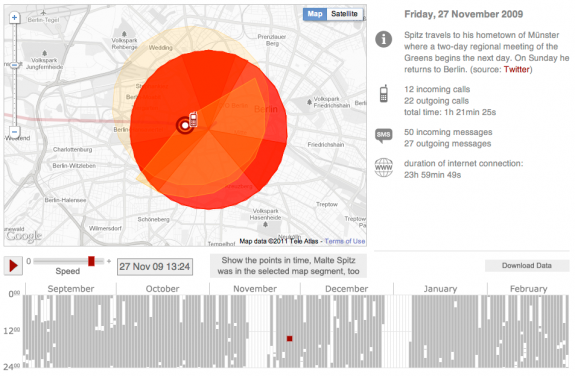

As the German government tries to come to a consensus about its data retention rules, Green party politician Malte Spitz retrieved six months of phone data from Deutsche Telekom (by suing them), to show what you can get from a little bit of private mobile data. He handed the data to Zeit Online, and they in turn mapped and animated practically every one of Spitz’ moves over half a year and combined it with publicly available information from sources such as his appointment website, blog, and Twitter feed for more context.

This profile reveals when Spitz walked down the street, when he took a train, when he was in an airplane. It shows where he was in the cities he visited. It shows when he worked and when he slept, when he could be reached by phone and when was unavailable. It shows when he preferred to talk on his phone and when he preferred to send a text message. It shows which beer gardens he liked to visit in his free time. All in all, it reveals an entire life.

Press the play button and watch him go, or use the timeline on the bottom to skip to specific spots. Slick, well-designed, and thorough reporting.

Want to see the data for yourself? Download the spreadsheet. Zeit did omit phone numbers, but it should be easy to see how that could add a whole other level of complexity.

Then again, some people already share all this information via Foursquare and Twitter. Is that a good thing?

[Zeit Online via @aaronkoblin]

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

This is such an amazing execution, implementation, data set and demonstration of the power of data viz. In my mind this is the best data viz of the last 12+ months.

As an aside it really seems that Europeans are creating the most innovative and best executed visualisations at the moment.

This is brilliant stuff.

After seeing this I am feeling slightly better that I can never get a signal on my phone. :-)

It begs the question whether we have mobile phone signatures. Given that our mobile phones are arguably the most personal of technology devices, do we each have some sort of mobile phone “fingerpint” or “signature”? If so, does that mean we are never really anonymous?

Your phone is as unique as your fingerprint.

What people are REALLY fearful of concerning their privacy given all of this information: no one cares enough to pay attention to them. Better that access to this data be criminalized than that i be ignored.

I turned off my location services on my iPhone this weekend! Yes, people do share their information on social networking sites, but as with any raw data, it’s somewhat useless without context. When visualized and plotted out on a map, the scary thing is to see the patterns that emerge and the clusters that form — showing the places that you frequent most, and at what time. Imagine what ill-intentioned people can do with this type of information!

@Cecilia: Each phone on GSM-style networks has a unique hardware ID (called an IMEI), and all cell phone subscribers have a unique IMSI (“International Mobile Subscriber Identity”). Likely the link between your IMSI and your actual identity is held by your cell phone plan provider. However, your IMSI is handled by any cell phone tower that you connect to, and likely ends up in a lot of databases around the world.

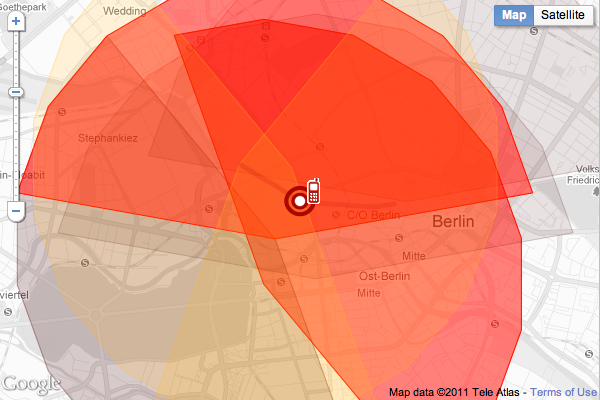

@Stella: Turning off location services is a good first step, as it inhibits the submission of your location to web sites and applications that may use that data in unknown ways. However, simply by dint of your cell phone being powered on with its radios active (on an iPhone, this is any powered-on state except for “Airplane Mode”), your location can be pinpointed and tracked with a surprising degree of accuracy. Your phone is constantly “pinging” the mobile network, which keeps track of which cell phone tower(s) you are closest to. The owners of those towers, and the mobile phone networks that use them, have access to this kind of location data with fairly high resolution in both time and space.

Now, with Location Services, your location is likely more accurate, but even these radio-based modes (which, by the way, work with *all* cell phones, not just “smart” phones) can achieve a spatial resolution of under 1000 meters. In urban areas, that resolution is frequently much higher, because the towers are spaced much closer together.

It’s merserizing to hit “play” and follow Herr Spitz’ life. Excellent execution. Raises all sortsd of privacy questions in the moden age. Until — until one considers that people have created diaries of their lives for generations. I live in Massachusetts, where the state historical society is commemorating John Quincy Adams’ diplomatic service to the US some 200 years ago, when he served as our minister to Russia. JQA wrote daily brief diary entries, and the Massachusetts Historical Society realized that most all of them would have made excellent Twitter tweets, had the technology been available. So the society has been tweeting JQA’s life in Europe daily, 200 years late. The feed is here: http://www.twitter.com/JQAdams_MHS.

My point: Using JQA’s tweets (um, diary entries), we could produce a similar graphic image. Obviously, transportation was slower in the 19th century, but the art of politics and diplomacy has needs and rythyms that don’t change much over time. I suspect there’d be similaritiies. And we are able, in the case of John Quincy Adams, to follow his whereabouts over time nearly to the degree possible with Herr Spitz.

Of course, the biggest change is that JQA controlled who saw his diary and largely controlled who knew where he was and where he had been. Herr Spitz let Deutsche Telekom and the social networks have the information in exchange for instant telecommunications.

Fascinating example.