I am starting to hear about Charles Minard’s map of Napoleon’s march time and time again – almost to the point of exhaustion. Is the map really that awesome, or is it just because Edward Tufte said so? Here is my question to all of you:

Is Minard’s map the best statistical graphic ever drawn?

I have my own thoughts about this, but more importantly, I want to know what you all think. If you don’t think it’s the best ever, what is? If you do think it’s the greatest of all time, what’s second best?

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

Visualize This: The FlowingData Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics (2nd Edition)

I don’t think its the best ever. I think that it’s very innovative for the times it was created in, don’t you think? BTW I don’t think it is the most innovative of historical graphs mentioned in the book. Do you remember the chart showing French train schedule? Don’t you think this one is extremely clever?

Impossible to say if its the best ever, but it clearly is one of the best examples out there. Its increasing popularity also adds on to its status as a great graph. For the time when it was created it was clearly innovative, and for the times we are living now it keeps opening infographical roads.

I had an immediate emotional and rational response to it when I first saw it, something very similar to a “wtf! this is genious!”, and although the overuse of it in conferences and papers is making it a bit of an overplayed record, every time I see it it keeps creating the sense of wonder.

It’s true that it needs a little explanation, but it’s also true that it is “little” what it reqires. Plus I haven’t yet seen one graph that does it all on itself (please enlighten me if you have).

How can it be the best? There are no glittery effects, no gradients and shadows and 3D text. He didn’t even create it in Illustrator!

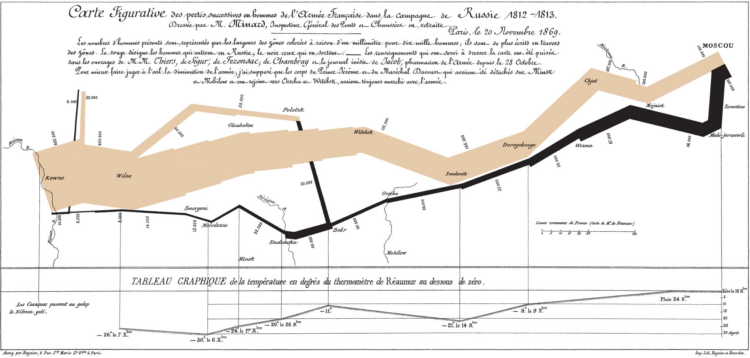

But seriously, it is a very interesting and data-heavy graphic. Seth Godin doesn’t like it, it takes too long to understand, and it violates the one message per chart rule. Well, the message is that Napoleon’s March was a huge blunder. All the nuance Godin dislikes details the distances traveled, the losses along the way, the debilitating cold on the return march.

I don’t know if it’s the best ever, but it’s very well planned and executed.

Seth Godin doesn’t like it? Is that supposed to inform my opinion on the Minard map somehow?

Interestingly enough, I just posted about the Minard map earlier this week, albeit tangentially, in relation to military imaging/visualization. What interests me about the graphic is how well it handles geography, time, the data being tracked (number of soldiers) AND it works as a historical document. It functions on so many levels! I think it really merits all the attention it continues to receive.

I do find it a little strange that infovis enthusiasts fall back on the same point of references over and over and over when discussing the field. Oh look.. The Dumpster again. Oh.. wow Textarc, I’ve only seen that project 24 times a year since 2001.. but I guess graphic and design culture can be a bit like pop music at times in that the chosen (and often prescient) few become the anointed ones.

Best ever? Well, who can ever say.

But it’s a brilliant piece of work (albeit a bit overexposed these days, as the commenters have noted).

I disagree that a graphic should make one point, and make it instantly clear — although that is sometimes what you want.

The best graphics make complex notions comprehensible. The more you look, the more you see. Some things in the world are a genuinely complex, and you can’t distill them into a “sight bite”. This is a graphic that, as you look, more and more relationships become clear. Yes, you do have to spend a few minutes with it, but for me they were productive and enjoyable minutes — and far fewer than I would have spent reading an article explaining all of what’s in the chart.

Best ever? Well, who can ever say.

But it’s a brilliant piece of work (albeit a bit overexposed these days, as the commenters have noted).

I disagree that a graphic should make one point, and make it instantly clear — although that is sometimes what you want.

The best graphics make complex notions comprehensible. The more you look, the more you see. Some things in the world are a genuinely complex, and you can’t distill them into a “sight bite”. This is a graphic that, as you look, more and more relationships become clear. Yes, you do have to spend a few minutes with it, but for me they were productive and enjoyable minutes — and far fewer than I would have spent reading an article explaining all of what’s in the chart.

Whilst I find myself ocasionally irritated by Tufte’s dogmatic approach Minard’s graphic really is great. As has been mentioned it’s was groundbreaking at the time, there’s many layers of data available and it rewards close study with greater understanding of the subject it illustrates. true it’s not immediately obvious what’s going on, but then it wasn’t produced for the front page of USA Today, graphics don’t all have to be designed for the same audience. As for the question of whether it’s “the best”? I don’t know it depends what you’re talking about. It’s almost certainly the best infographic showing Napoleons campaign against Russia.

Further I think the idea that graphics can only say one thing is really restrictive, that rules out almost all visualisation that’s used for exploring data sets rather than making a point, sometimes you visualise data to find out what its interesting features are rather than the other way around. The idea that all graphics should be for the same thing. i.e. instantly making a point, is a great way to cut off huge swathes of infographic potential and if you stick to it you’ll potentially dismiss great ideas and new solutions like Minard’s before they even get onto the drawing board.

how can any graph be the best ever? a graph is well suited for a specific context and audience.

conceptually, this graph was very innovating in its age, which makes it an interesting and worthy study object.

that being said, I cannot agree with Tufte’s dogmatic approach on data-ink and junk chart and being fascinated by the fact that it encodes 6 or 7 variables in one display. It does so at the price of being difficult to understand at first glance. in today’s world, in most contexts, people will not devote enough time and attention to understand an author’s intentions least they are obvious.

on top of that I admit that my mind tends to switch off when I see it in a presentation especially presented as the ultimate graph. especially in an age where clever researchers come up with clever designs every month, every week, every day.

to sum it up: not the best graph. worth knowing. presenters who use it lose credibility.

It’s a phenominal graph considering the time in which it was created and the techniques used to make it. Don’t know about the best graph *ever*. But certainly makes the short list of graphs to remember.

It’s a powerful graph because, beyond the visuals, it tells an incredible story and wonderfully captures a critical turning point in Napoleon’s conquest.

It’s a phenominal graph considering the time in which it was created and the techniques used to make it. Don’t know about the best graph *ever*. But certainly makes the short list of graphs to remember.

It’s a powerful graph because, beyond the visuals, it tells an incredible story and wonderfully captures a critical turning point in Napoleon’s conquest.

It’s a great graphic. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia may not resonate with modern American audiences, but it was a defining episode in European and military history. Napoleon’s invasion provides the background for Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the world’s greatest novel. Certainly, this graph illustrates a complex event that encompasses libraries of commentary.

The graph illustrates an amazing point — how an army of 400,000 can dwindle to 10,000 without losing a single major battle. I remember coming across a derivative graph in the excellent two volume historical atlas by Kinder and Hilgemann and being struck by it. The original is even better.

This is a great infographic. Perhaps one that could only be best represented by the supremely Cartesian yet artistic sensibilities of a Frenchman.

It’s a great graphic. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia may not resonate with modern American audiences, but it was a defining episode in European and military history. Napoleon’s invasion provides the background for Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the world’s greatest novel. Certainly, this graph illustrates a complex event that encompasses libraries of commentary.

The graph illustrates an amazing point — how an army of 400,000 can dwindle to 10,000 without losing a single major battle. I remember coming across a derivative graph in the excellent two volume historical atlas by Kinder and Hilgemann and being struck by it. The original is even better.

This is a great infographic. Perhaps one that could only be best represented by the supremely Cartesian yet artistic sensibilities of a Frenchman.

jerome hit the nail on the head “how can any graph be the best ever? a graph is well suited for a specific context and audience.”

The four main variables are troop size, temperature, location, and time. Bringing 4 variables together in a two-dimensional graph in a comparatively simple way vis-a-vis a 3D graph with motion shows Minard’s craftsmanship. Best? Well, we all know it’s a loaded question that we are willing to debate the merits of =). I certainly would nominate it for ‘Best of’

jerome hit the nail on the head “how can any graph be the best ever? a graph is well suited for a specific context and audience.”

The four main variables are troop size, temperature, location, and time. Bringing 4 variables together in a two-dimensional graph in a comparatively simple way vis-a-vis a 3D graph with motion shows Minard’s craftsmanship. Best? Well, we all know it’s a loaded question that we are willing to debate the merits of =). I certainly would nominate it for ‘Best of’

it’s hard to say a graph is the best, but i think it’s hard in the same way that ranking the best movies of all time are, right? we can rank graphics based on design principles like color, organization, readability, etc. Of course, in the end it’s all a matter of taste, but that’s why it makes for good conversation (like we’re seeing here :) and helps us think about what’s good and what’s, um, not good.

it’s hard to say a graph is the best, but i think it’s hard in the same way that ranking the best movies of all time are, right? we can rank graphics based on design principles like color, organization, readability, etc. Of course, in the end it’s all a matter of taste, but that’s why it makes for good conversation (like we’re seeing here :) and helps us think about what’s good and what’s, um, not good.

It’s great, awesome, impressive.

It does get tired after a while, though. If I see it in one more presentation, I may just jump off a bridge. :) For a group of creative folks, you’d hope we’d have more good examples to learn from.

Read one of the many books on the march and you’ll see how the immense suffering and tragedy is efficiently summed up in one multi-dimensional graph.

For example, it’s crucial that the temperature is charted during the retreat because the cold (down to -30C/-22F) had a severe effect on the ill-equipped French soldiers and their allies.

Ambrose – I couldn’t agree more. Even in the more quantitative areas, it’s a recurring example.

Victor – that’s another really good “metric” to go by. evoking emotion, which the minard achieves on some levels.

A couple of subjects brought up earlier – seth godin one point and instant recognition. we should keep seth godin’s audience in mind and the medium which is business powerpoint.

and then the instant recognition thing – do we need to understand a graphic immediately for it to be good? if the data are simple or we are presenting in a talk, then yeah, probably, but what about for print, online, or exploratory data analysis?

I think that Minard was really innovative at his time but I’m sure one could make a “better” graphic with the same data now (clearer, faster to read, maybe with more info).

Someone shoud organize a “Beat Minard Graphic” contest. Could be fun :).

Honestly, what’s so good about it? I feel like it needs explanation and diverges enough from people’s mental construct of an infographic that makes it largely unusable.

I agree with Seth Godin, it sucks. It might have been innovative back then but it has a high aesthetic/low performance quotient.

Also agree with MB’s comment, the train schedule is way better.

Ash – It’s not a pie chart, it’s an infographic. Pie charts need little explanation and their information can be assimilated in seconds. An infographic with such a large density of information requires several minutes to understand. Given that Menard didn’t have access to computers, clip art, etc., I think his infographics rate highly in comparison to, e.g., those in the NY Times. Compared to the various word clouds and pseudo-network diagrams we see so many of, Menard’s rates head and shoulders above.

Ash – It’s not a pie chart, it’s an infographic. Pie charts need little explanation and their information can be assimilated in seconds. An infographic with such a large density of information requires several minutes to understand. Given that Menard didn’t have access to computers, clip art, etc., I think his infographics rate highly in comparison to, e.g., those in the NY Times. Compared to the various word clouds and pseudo-network diagrams we see so many of, Menard’s rates head and shoulders above.

No, it’s clearly not the best. It’s very good from a design standpoint, but it resulted in nothing. Napoleon had already lost.

So, what’s better?

I’d nominate Snow’s graphic http://www.ncgia.ucsb.edu/pubs/snow/snow.html

which deals with the source of a cholera epidemic being a specific well, and reflects analytic processes Snow was using to figure out how to deal with the epidemic.

This sort of graphic is very common today (e.g. laying out your customers on a map). What did the Napoleon graph lead to? I can’t think of a lot of graphics which are like it.

I like Cedric’s idea:

“Someone shoud organize a “Beat Minard Graphic†contest. Could be fun :). ”

Who’s got the data?

actually, i think i have the data somewhere. i’ll consider it

I think this graphic was highly innovative and very informative considering the time when it was created. It imparts a significant amount of information and gets a point across without resorting to copious amounts of text or data tables (something many could learn from today). I am a fan of the work and ideas of Tufte and do refer to his visual information techniques at the office and use many of his principles to abstract or convey complex information when appropriate.

There are a few versions of the data (and electronically recreated versions of the plot) available at http://www.math.yorku.ca/SCS/Gallery/re-minard.html

While the Minard infograph was an innovation for its time, it did not set a trend that has continued to this day (as with Snows) and did not change Public or Military practice

A better competitior for ‘best graphs’ would be the series Forence Nightingale created during the Crimean war between Britain and Russia.

These charts would be instantly recognisable to Analysts today and were immediately powerful in their own time > Transforming Military medical care to reduce disease and infection casualties both in and out of combat > and creating (or perhaps publicly validating) the proffession of Nurses.